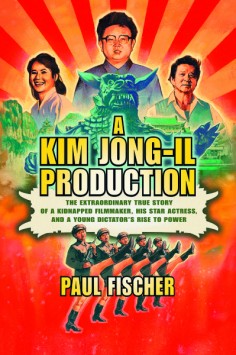

A Kim Jong-Il Production: The Extraordinary True Story of a Kidnapped Filmmaker, His Star Actress, and a Young Dictator’s Rise to Power

by Paul Fischer. New York: Flatiron Books, 2015. 383 pp., illus. Hardcover: $27.99.

Reviewed by Christoph Huber

Less a specialized film book than a populist true crime thriller, Paul Fischer’s A Kim Jong-Il Production tries to untangle one of the strangest affairs in cinema history, while adding some fascinating background to the scarce literature about the evolution of cinema in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. To this day, the totalitarian state of North Korea remains something of an enigma to the Western Hemisphere. The regime’s bizarre and extreme cult of personality surrounding the leading family of Kims (“Dear Leader” Kim Jong-Il, one of the book’s protagonists, represents the second generation in a trinity of godlike dictators) and a twin policy of ultra-Stalinoid propaganda and near-total seclusion has encouraged, given the difficulty of obtaining verifiable inside information, a contradictory view of North Korea in the West. This was reinforced by last year’s affair surrounding the release of the Hollywood comedy The Interview, which was predicated upon the assassination of the country’s current supreme leader Kim Jong-un and provoked protests from Pyongyang about this filmic “act of war” that culminated in a notorious cyber-attack on Sony Pictures, the film’s producer. While Cineaste used the occasion for a welcome and well-considered examination of the recent wave of films trying to make sense (or fun, or both) of a seemingly inscrutable totalitarian regime, most of the media frenzy simply catered to the conflicting Western notion of North Korea as both a bête noire and a joke—a hermit kingdom seen as both ridiculously powerless and dangerously unpredictable.

Although one of the incontestable achievements of Fischer’s book is to shed some light on the inner workings of North Korean policy, it can hardly be considered a re-evaluation of these received ideas. Recounting a truly extraordinary story—the title is certainly not just a sales pitch—Fischer frequently veers from hilarious absurdity to pure horror as he tries to cobble together the facts about one of the most blatant cases of dictatorial cinephilia. Famous for his love of movies, Kim Jong-Il not only assembled a personal collection to make any major film archive blush with envy, he also envisioned a national film production to rival the entertainment behemoth of the enemy’s dream factories, but recast to serve the doctrine of North Korea’s Juche ideology of self-reliance, as laid out in his incomparable 1973 volume, On the Art of the Cinema. Although the results were clearly hampered by production circumstances, propagandistic purposes, and lack of experience in the technical departments, film ruled literally, certainly within the borders of the Democratic People’s Republic, where the populace had no other viewing choices but to attend the mandatory screenings of homegrown output. This situation changed when black-market alternatives arose in the 1980’s, with VHS cassettes and DVDs smuggled in, usually via China. Like many things in North Korea, the punishment for watching these outlawed movies was draconian, but the lure of glimpsing the forbidden outside world—a completely unknown realm to younger viewers—proved irresistible to many.

What’s more, these foreign films were decidedly different from the monotonous product mandated by Kim, as he only knew too well, being a voracious connoisseur of juvenile capitalist pleasures like the James Bond and the Friday the 13th series. Meanwhile, Kim’s dream of international acclaim for his ciné-Juche was one of the delusions impossible to support even within the warped alternate universe conjured by his insular regime. Possibly drawing on his movie-fueled passion for international espionage—by all accounts, he considered the Western fantasies he loved, including the Rambo and Bond films, as realistic representations, possibly even docudramas—Kim decided to give the ailing art of the (North Korean) cinema a boost by abducting South Korea’s most beloved female star, Choi Eun-hee, as well as her ex-husband, noted director Shin Sang-ok, in the late 1970’s.

At least that is what the two victims claimed later. Their story, full of unbelievable and sometimes conflicting details, has been frequently disputed, not least because they gave press conferences singing the Democratic People’s Republic praises once they had been successfully indoctrinated in a grueling process over several years of imprisonment (the hardcore type for Shin, a more luxurious one for Choi). Fischer convincingly argues that their pretend conversion was just a means to keep open a window of opportunity to escape, which they managed during a heavily guarded trip to Vienna for international co-production purposes in 1986, replete with a “Follow that cab!” chase climax. Drawing on extensive research and numerous interviews, Fischer’s book may be faulted by nitpickers for improper sourcing and eschewing footnotes while telling most of the story in a you-are-there-fashion that includes reimagined (one imagines) dialogue and detailing his subjects’ subjective emotional states according to the rules of a suspense story rather than academic protocol. Still, he amasses so many salient specifics as to remove any doubts about the veracity of Shin’s and Choi’s claims after their successful escape…

To read the complete review, click here so that you may order either a subscription to begin with our Fall 2015 issue, or order a copy of this issue.

Copyright © 2015 by Cineaste Magazine

Cineaste, Vol. XL, No. 4