Two Shots Fired: An Interview with Martín Rejtman (Web Exclusive)

by Aaron Cutler

The film Two Shots Fired (2014) begins with a teenager dancing by himself in a nightclub. We then see Mariano (played by Rafael Federman) leaving the club and riding a bus back to his home in Buenos Aires’s western suburbs. On the following day—the hottest day of the year—he takes a swim, mows the lawn, finds a handgun in a toolshed, enters his bedroom, and shoots himself twice. He returns home a week later, having seemingly fully recovered. The first bullet only grazed his head, we learn, and has left a hole in the bedroom’s ceiling. The second bullet’s location soon grows evident: Mariano sets off another club’s metal detector and emits strange whistling sounds when he plays his recorder, while doing his best not to seem out of place.

The film initially looks like it will trace the impact of Mariano’s self-attack (for which he blames the weather) on him and on his surroundings. The household dog Yago runs away, perhaps to live with another clan. Mariano’s vigilant single mother, Susana (Susana Pampín), keeps watch for the pet while hiding her kitchen knives, calling Mariano’s cell phone frequently, and urging her quiet, obedient, self-sufficient older son Ezequiel (Benjamín Coelho) to take Mariano to live with him in his apartment.

Over time, it grows clear that the incident, more than anything else, has marked an occasion to begin studying these three people, who always act according to their natures. As in the fifty-four-year-old filmmaker Martín Rejtman’s previous films, much of the ample humor of Two Shots Fired results from watching people respond in the same ways to each new situation that they encounter. The family’s constancy becomes apparent as the film leaves its initial trauma to drop its leads into new plots, with Mariano’s brief past-tense descriptions of events in voice-over sometimes serving as connective threads between scenes.

Mariano’s posture remains torn between leaning toward and away from people as his recorder quartet takes on a new member and tries to play over his echo. Ezequiel stays slightly hunched and with an open but apprehensive gaze toward his kin as well as toward Ana (Camila Fabbri), an attractive attendant at his favorite fast-food restaurant whose attentions he haltingly pursues. Susana, a lawyer, stays firm and quiet as she sorts through confusion—first in her home, and then on a beach trip that she takes with a group of strangers and near-strangers in an ill-conceived bid to calm her nerves.

To some extent, the ongoing flux in which these people live arises from their desires to avoid confrontation—with others, and with themselves. Over the course of Two Shots Fired’s many short, linearly arranged scenes, they run through conversations weighted toward the logistical side of life: They speak about where they will go and whom they will meet, and almost never about their feelings.

The film’s characters behave like figures from throughout Rejtman’s previous works, which include four features and two medium-length films to date along with five published books of short stories (none of which has yet been translated into English). His people walk in various poses of self-protection, and bounce from isolation to near-connection with each other back to being alone again without appearing much perturbed. They show up repeatedly in the same mundane public settings (including airports, video arcades, discotheques, and cheap restaurants) as though nothing fundamental were changing for them. This sense is emphasized in Rejtman’s films through the even-keeled performances of many of his actors, whose divergent pitches emerge over the course of their consistent, flat line deliveries. The emotions lie buried beneath the words.

Each of Rejtman’s features begins with upheaval in a character’s life and proceeds on a path towards stability. At the outset of his debut feature, Rapado(a.k.a. Shaved, 1992), the teenage Lucio (Ezequiel Cavia) is robbed of his motorcycle and wallet and given counterfeit money by a friend; he soon gets his head shaved at a barbershop and nocturnally wanders the streets until he acquires a moped and, perhaps, a new friendship. In Silvia Prieto (1999), the title character (Rosario Bléfari) begins her twenty-seventh year with a new job and a potential boyfriend, then moves on to other professions and possible partners while trying to accept the upsetting news that another woman with her name lives in Buenos Aires. In The Magic Gloves (2003), the thirty-five-year-old mopey freelance motorist Alejandro (Gabriel Fernández Capello, a.k.a. the musician and composer Vicentico) enters relationships with people whose self-improvement schemes lead him to sell, buy back, and resell his prized Renault before he settles into work as a bus driver.

Rejtman’s work holds great significance within recent Argentinian cinema. Rapado broke with the country’s then-dominant modes of naturalistic filmmaking and helped start a wave of low-budget alternative works known today as the New Argentine Cinema, whose important filmmakers came to include Rejtman along with Alejandro Agresti, Lisandro Alonso, Lucrecia Martel, Raúl Perrone, and others. As is often the case in film history, the careers of many of this movement’s filmmakers have outlived it, with each artist developing along his or particular path; for Rejtman, this has entailed an expanding universe of idiosyncratic behaviors unfolding amidst nondescript surfaces.

His films all take place in Argentina and—save for the hour-long documentary Copacabana (2007), a record of Bolivian émigrés to Buenos Aires preparing for their annual Virgin of Copacabana celebration—focus on natives to the country. Critics have often read the films (like ones from several of Rejtman’s peers) as national allegories, with Argentina’s economic fluctuations over the past few decades perceived through the ease and frequency with which characters change circumstances. Such readings, though, while potentially valid, risk belying these films' particular, personal natures. They give the oddly comforting sense that you can change your life and remain yourself, even if it’s not clear who that self is. Two Shots Fired contains the largest ensemble of actors with which Rejtman has worked, and yet each of its characters registers delicately. —Aaron Cutler

Two Shots Fired begins with teenager Mariano (Rafael Federman) shooting himself, only to recover soon afterwards

*****

Cineaste: How did Two Shots Fired come about?

Martín Rejtman: I was once at a film festival in a northern Argentinian city called Salta. The eventual editor of Two Shots Fired, Martín Mainoli, who used to be my student and is now a friend, is from there and was with me. The festival was screening Rapado. Martín pointed at a guy coming into the theater and said that it was the third or fourth time that the man was seeing the film—it only played at festivals there, but every time it played, he saw it. Martín also mentioned in passing that the guy had shot himself twice and survived. I took this bizarre image with me, and I used it to begin building a script.

I always try to think of a story together with its characters. It’s not that I think of a character because of something particularly interesting about him or her. It’s more that he or she is part of a situation I like, and I continue to develop the character as I find other situations I like for them.

In this case, I came up with a family of three people—the mother Susana and her two sons, Mariano and Ezequiel. The film starts with Mariano and his voice-over narration, thus his point of view, and continues with him and his family members after he shoots himself twice. The brothers eventually disappear as we follow Susana to the beach with some other people, and then we return with her and end the film with Ezequiel.

Susana is played by Susana Pampín, with whom I also made Silvia Prieto and The Magic Gloves. I basically wrote the part with her in mind. She is a very good, established actress, in contrast to Rafael Federman and Benjamín Coelho, both of whom are just beginning their careers. I thought that the weight of her presence could bring a sense of balance to the family.

Ezequiel is the older brother. I wanted him to be the one who takes care of situations. He is supposed to be the strong figure, but he’s weak for a strong figure, which creates a tension I like.

Mariano reminds me of myself when I was a teenager—I used to play the recorder in a musical quartet, and many other things that he does are things I did. Rafael and I also have similar roots. He went to my high school, both our birthdays fall in early January, and we are both Jewish. I thought he was interesting for the role of Mariano in that he seemed very firm and decided, yet also fragile.

Cineaste: Why does Mariano shoot himself?

Rejtman: Because it’s very hot. My idea was that the weather was so hot that you would do things you wouldn’t normally do. Also, when you find a gun, you either have to hide it or do something with it, so he decides to do something. He mentions in voice-over that the first bullet grazed his head, which is why he could survive to shoot himself a second time.

The consequences of Mariano retaining the second bullet aren’t really that bad. Not getting into a club is not such a bad thing. It could happen to anyone, not just because of a bullet, but also because of appearance. The sound he emits when he plays the recorder makes a difference, but he still stays in his quartet for a long time afterwards. I don’t think that the shooting changes much of Mariano’s life. I think he’s just a little different.

I am always more interested in little differences than in big ones. I am interested in making things equal in a film, but I am conscious that you need a little imbalance and some differences for the sake of drama. You need some kind of tension to bring a situation to life—if there are no oppositions or contradictions, then there is only flatness. Maybe this is why my characters are sometimes seemingly neutral, but also capricious. They don’t understand their own actions, but they also don’t seem to be affected by things in the same ways that other people are.

Cineaste: You often align characters in surprising ways. For instance, Susana doesn’t go to the beach with her sons or with anyone else close to her. Instead, she travels with Mariano’s young music teacher, Margarita (Laura Paredes), and with a complaining middle-aged stranger named Liliana (Daniela Pal) who offers to help pay for expenses but exasperates her fellow travelers. Margarita we have met a few times in the film prior to this trip; Liliana we haven’t met at all, and she exits the film before some viewers might be able to get used to her. Why join such personalities?

Rejtman: In that case, they are three people who don’t know each other, and I wanted to see what would happen when I put them together. Susana doesn’t seem to have any friends (at least, we never see her with any) and so takes Margarita with her to travel. Liliana comes by chance—she needs a ride, and they end up together. Lili is irritating and kind of obnoxious. At the same time, she is lovable because she’s fragile in her own way.

I wrote Liliana’s part because there are many great Argentinian actresses her age. The talent in terms of actresses older than forty here is huge, and I wanted to draw from it. One of the differences between film and literature is that when you write a screenplay you have to think about who is available that you will want to work with. I had to find good actors and actresses who would be comfortable working with me, and who would also understand how I wanted them to act.

Cineaste: What is particular to your way of working with actors?

Rejtman: I want the script to be really respected. I want the actors to know their lines, and I don’t want them to change the lines unless we agree to change them. My starting point is always the dialogue. The rest we will find after the lines are learned.

I rehearse a lot in order to make sure that the actors know their lines. I also do it in order to get the right rhythm and music for the scenes. By “music,” I mean the way people talk. The intonation, the rhythm, the pauses between words, the slowness or speed at which characters speak (because they often speak very quickly in my films), all this is already written into the script. When I write a screenplay, it’s like I listen to a score, and I need its sounds to be reproduced in the film.

This takes a lot of rehearsal, with which some actors are not so comfortable. It’s like I prefer to work from the outside toward the inside, focusing only upon what is immediately visible, while many actors prefer to work from inside to outside. I want them to go to different places than where they might typically go, and over time they get used to doing this.

Cineaste: What do you feel that the actors bring to the process?

Rejtman: They bring a lot. First they bring their presence. Sometimes actors think that they are not doing enough to create a character, and that they need to do more because otherwise they are not fulfilling their job, but in an actor the character should already be present somehow. It could be a small percentage or a bigger one, but some of the character should be inside the actor before I pick him or her. That’s what I look for in the casting process—to see if that part is there. By the time that we get to the moment of shooting, the characters must be completely there.

Sometimes the characters grow in the actors little by little, and sometimes they just appear. It varies from case to case. I can give the example of Fabián Arenillas, who plays Liliana’s ex-husband, Arturo, who briefly comes to the beach. I had previously worked with Fabián on The Magic Gloves and on a made-for-television film called Elementary Training for Actors (2009, co-directed with Federico León), but I didn’t imagine him when I wrote the part. We auditioned many actors his age until I finally called him. He came and read, and he was there already. We didn’t need to rehearse or look for anything—he knew (or, I could say, he was) exactly what was needed.

Another example is Benjamín Coelho, who was asking me for more information in many instances. There is a scene in which Ezequiel is standing next to Susana as she tells him to take Mariano to live with him, and Benjamín didn’t know what to do during it. He wanted more direction. He wanted to know how he should feel and what to think. I told him some things, but I couldn’t enter Ezequiel’s mind. He had to do his own imaginary work.

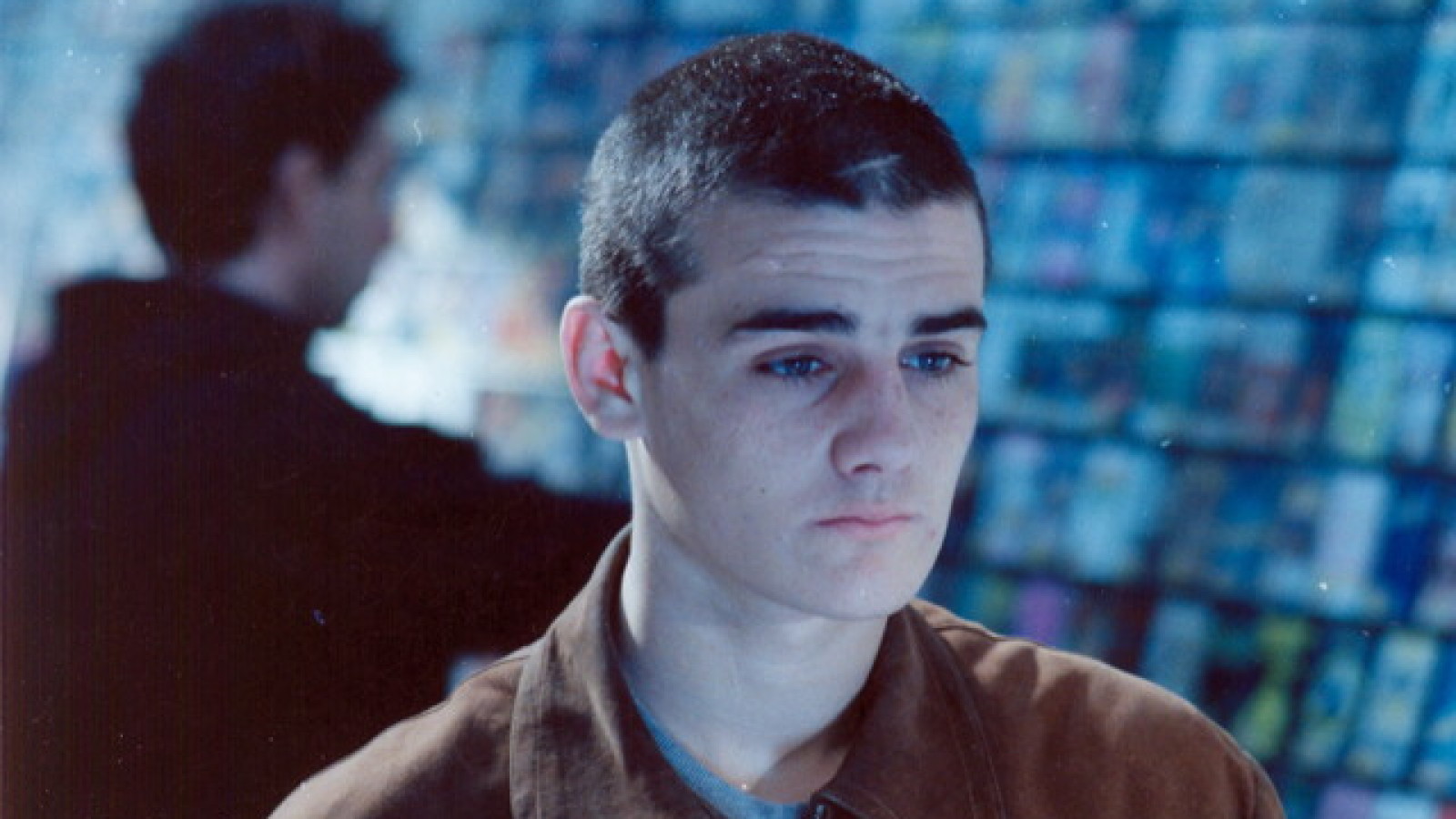

Ezequiel (Benjamín Coelho) encounters Ana (Camila Fabri) in a record store

I found Benjamín on a recommendation from an actress who was his teacher. I can’t say exactly why I chose him. It’s always in comparison with other people. Sometimes it’s not that I see a face and a way of acting and say, “This is the person,” but I look at him or her among all the others and say, “This is the one that stands out.”

Cineaste: How do you feel about working with actors with whom you’ve previously worked versus working with actors new to you?

Rejtman: I really like working with actors with whom I’ve worked before. They know what I want, and I know that they know what I want, so it’s very comfortable. Also if I’ve picked an actor for a film and then pick him or her again later, it means that I am comfortable with him or her as a person. When I look at all the films I’ve made and see the same actors, but younger, I enjoy thinking that they have kept working with me throughout the years. It gives me a sense that I have accomplished something.

I am very shy, and working with new actors makes me nervous. In this film I had many new actors and it took me a little while to get comfortable with them. With that said, I like all of my actors. Sometimes I get insecure while we are working and think that maybe they are not the right ones, or that they believe that I don’t know what I am doing, but we work and work together and reach something with which we are satisfied.

Cineaste: Several of Two Shots Fired’s actors and characters are young. What interests you in telling stories about young people?

Rejtman: I started writing in my teens and early twenties. It’s a moment when people are still defining themselves. People are a little undefined when they are young, and I like lack of definition of characters. You cannot have it in all of them, but in some characters I like it because it’s a way for them to be permeable to others. Some of my characters who are older seem to have this same quality of permeability. They are a little childish. If you are an adult and act like a kid, then there is already something there to make a character alive.

I need characters to be complex and to have many faces, both in my films and in my short stories. The short stories relate the same kinds of experiences that the films do, with the same kinds of characters and reactions. If you look at the books I wrote alongside the contemporaneous movies I made, then you will find similarities in tone and in atmosphere and in the way that stories are told.

I adapted Rapado from a short story that I had written. At the time that I conceived of the film, I felt that people in Argentina were less interested in making films than in telling audiences about their ideas. I didn’t like how characters were talking in the Argentinian films I saw, so I had to create my own form of film dialogue. That took me time.

In the beginning, I preferred not to have a lot of speech. My early films, like my early prose fictions, were less comic and more contemplative. I made a short film called Doli Goes Home (1984/2004) in which the characters talked even less than in Rapado. There is also almost no humor in that film—there are things in it that could be funny, but in ways that are really dry.

I could have gone on to make only contemplative films. It would have been an easy path for me. Somehow, though, I felt I had to do something else. I needed some kind of edge, and I eventually discovered that humor brought it. I started introducing humor into my films, along with other elements. I shot Doli Goes Home in black and white, and then later I began to use color, along with more dialogue and more action. The films began to move faster.

Little by little, I have freed myself. There is a greater mix of characters in Two Shots Fired than in my previous films. In Rapado I focused on late teenagers, then in Silvia Prieto upon people in their twenties, and then people in their late thirties in The Magic Gloves, while here there is a combination. My previous films were fairly closed in their structures, while this one is a bit more open. There are more stories now, and I move between them in a more expansive way.

If you look at my most recent story collection, Tres Cuentos (a.k.a.Three Stories, 2012), then I believe that you will see something similar to what I just described about Two Shots Fired. Of course, there are still differences between my films and my short stories. In the short stories I sometimes go back and tell something that previously happened to characters, for instance, while in my movies I never do that. It’s this idea of always being in the present. That’s cinema for me.

You can go back in time in films. Sometimes it’s really nice, and maybe someday I will do it, but it’s like introducing a close-up. When you use long shots throughout a film and then introduce a close-up, that close-up becomes very strong and important. So if I ever use a flashback, then it’s going to be important, because I haven’t used them before. But I don’t say no to anything.

Cineaste: You have also avoided using musical scores in your films.

Rejtman: In Rapado I have a little bit of nondiegetic music, but yes, in my other films I don’t. I choose not to have it so that I can plan my soundtracks more carefully. I am very attentive to every sound in a film, and I want that attention to come without the interference of music that would bury the reality of those sounds. For me the ideal of reality in a movie lies more in its sounds than in its images. Any image can be realistic somehow, but if the sound in a film isn’t right, then you’ve gotten everything wrong.

Sound mixing is actually my favorite part of filmmaking. When you begin to work on the sound mix, everything is very rough and raw. I enjoy it when sounds start getting right, when the voices begin to be equalized and you can hear the film come to life.

The original idea of Two Shots Fired is structured around the distorted recorder sound that Mariano produces after he gets the bullet inside of him. Everything else that’s in the film then has to do with sound. The writing of a film is not just the writing of a script. It’s a complex process that continues throughout editing and mixing. Until the very last moment of the sound mixing, I am writing the film.

Cineaste: Your films take place largely in and around Buenos Aires. How do you feel about working there?

Rejtman: The city is very noisy. It’s also quite mixed and eclectic in terms of its architecture. You can find a nineteenth-century building next to a recently built modern building and a small house beside a very large tower. At the same time, the scale doesn’t seem to have changed so much over time. It’s still a walkable city. Even though it’s chaotic, it’s not so difficult to grasp.

There are many things that I dislike about Buenos Aires. I think that there are more things that I dislike than things that I like about it, because I live here and have to make my films here. It’s sometimes very difficult to obtain a pure image in the city because of all the billboards and telephone cables and graffiti and dirt and rubbish. This is maybe why I am going more to the outskirts of Buenos Aires to work where it’s a little quieter.

I shot mainly in the outskirts for Two Shots Fired, in various neighborhoods, with the family’s house located in the western suburbs. There is only one sequence set in the downtown part of the city. Locations are like actors—they tell you something as soon as you see them. I wanted not to have an urban film. I wanted to follow my idea of digressing and of having a film that was not so centered.

Cineaste: How does this idea relate to the ways in which characters appear and disappear in the film?

Rejtman: That doesn’t have to do with the nature of the city. That has more to do with the nature of the narrative. I wanted the dog to run away at the beginning and then maybe appear again at the end, without your being certain that it’s the same dog. Mariano and Susana live together until Mariano moves to Ezequiel’s apartment, and then eventually, toward the film’s end, Susana decides that she would be happier switching with them and moving into the apartment while they take over the house.

The same elements remain, but their order changes during the film. You have the dog, but the dog goes to live elsewhere. You have Susana going to live where Ezequiel was living, and Mariano living with Ezequiel instead of with her. We are getting back into some sort of balance by the end, although things are more imbalanced than they used to be.

Ezequiel Cavia as Lucio in Rejtman's debut feature, Rapado (1992)

I think that this movement appears in all my films. In Rapado, Lucio loses his motorcycle in the first scene and eventually gets a moped. In Silvia Prieto, instead of meeting up with the poet Gabriel (played by Vicentico), Silvia meets another guy who takes Gabriel’s place with her. In The Magic Gloves, Alejandro sells his car and ends up driving a bus. There is always a sense of getting something back, even if it’s a little less than what you had before.

Cineaste: In addition to fiction films, you have made one documentary, Copacabana, which shows members of a Bolivian community in Buenos Aires as they prepare dances and musical parade numbers for a large religious celebration. How do you think that that film fits into your work?

Rejtman: Copacabana surprised me. I actually didn’t know how to shoot it when we started. The first few days we were trying different things until we realized that we had to shoot it the way in which we ultimately did, which was with almost no camera movements and with some distance, almost always showing people in long shots instead of in close-ups.

For me it became the same to shoot a scene of a documentary and of a fiction film because both cases involve placing a camera somewhere, having something happen with people in front of it, and then trying not to edit within scenes in favor of playing with transitions between them. I hope that this is not an approach that I impose, but one that comes from how I relate to my material.

I try to be flexible with how my films look. A standard art-house approach can feel too arty for my taste. I would prefer that a shot doesn’t call attention to itself, just like I would prefer that a style doesn’t call attention to itself. I think that my films could have been made a long time ago, when technique was not so evolved. I would like for them to be a little primitive and their style a little invisible.

Aaron Cutler keeps a film criticism site, The Moviegoer, at http://aaroncutler.tumblr.com.

This interview with Martín Rejtman took place after Two Shots Fired received its world premiere at last year’s Locarno International Film Festival and before the film’s screenings at the New York Film Festival. Two Shots Fired is distributed in the United States by Cinema Tropical. It will receive its U.S. theatrical premiere run from May 13-19, 2015, at the Film Society of Lincoln Center alongside a retrospective of Rejtman’s films.

Copyright © 2015 by Cineaste Magazine

Cineaste, Vol. XL, No. 2