FROM THE ARCHIVES: The Glory Brigade

Reviewed by Dan Georgakas

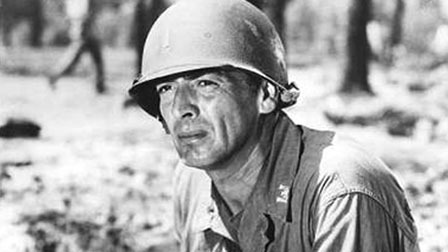

Victor Mature (left) as the Greek-American Lt. Pryor

Produced by William Bloom; directed by Robert D. Webb; screenplay by Franklin Coen; music by Lionel Newman; cinematography by Lucien Ballard; edited by Mario Morra; set decoration by Fred J. Rhode; starring Victor Mature, Alexander Scourby, Lee Marvin, and Nick Dennis. DVD, B&W, 81 min., 1953, A 20th Century Fox Cinema Archives release.

This otherwise run-of-the-mill war film of the 1950s merits consideration beyond its genre status due to its treatment of ethnicity in a turbulent time. All the action takes place during the Korean War (1950–53). The first sequences follow a valiant American platoon led by an apparently all-American guy, Lt. Sam Pryor (Victor Mature), a leader who enjoys the confidence and affection of his men.

Upon returning to a base camp where the troops are to rest, Pryor becomes informed of a battlefield problem. A unit will be going behind enemy lines to determine if the apparent movement of many enemy troops is a ruse. That operation is to be led by a Greek colonel. The Americans will provide river transport, but they will be under “foreign” command. This was a time when many in the U.S. military, officers and rank and file, were reluctant to work under non-American command, as the concept of NATO groups and UN units was still new.

When all of the American officers at the base camp express great reluctance to participate in the action, Lt. Pryor steps forward, saying he is the son of Greek immigrants and would be honored to work with fellow Greeks. He volunteers his unit to participate and his men, who would have preferred not to go back into battle immediately, support him.

This was a time when the children of European immigrants who arrived at the turn of the century in the Great Migration (1880–1924) had come to maturity. They considered themselves Americans and had complex feelings about the countries from which their parents had fled, sometimes rejecting “the old country” culture, sometimes romanticizing it. Pryor is the latter type. Marching to meet with the Greeks, he brags about his Greek heritage and speaks about Greeks as great warriors, casually mixing history and myth.

The first meeting with the Greeks is extremely cordial. Their contact in the field is the English-speaking Lt. Niklas (Alexander Scourby), who is from a privileged sector of Greek society, complete with pipe and upper-class manners. There is a “manly” round of drinking brandy followed by sequences in which Hollywood ethnic stereotyping momentarily takes over a conventional war film.

The Greek soldiers engage in vigorous and noisy Greek dancing. Lambs roast on spits and the whole scene resembles a Greek picnic. The Americans look on perplexed. Niklas tries to educate them by quoting from Palamas, a major Greek poet, about the need to dance before battle. Things get more serious when a priest in full vestments, stovepipe hat, and long hair conducts an open-air service. The Greeks become very dignified and the viewer understands they are indeed “devout God-fearing Christians.”

Pryor’s men take up defensive position near the spot from which they are to evacuate the Greeks when they return from their foray behind enemy lines. A series of incidents soon sours Pryor’s estimation of the Greeks. Some of his men witness a group of Greek prisoners who seem to have surrendered at first contact with the enemy. Another incident suggests the Greeks withdrew from a battle rather than fight. Pyror’s ethnic pride turns to contempt and then outrage when a detachment of his men is found slain where they were to rendezvous with the Greeks.

In due course, the surrender of some Greeks turns out to have been an act of courage to mask what the main force was doing. A roster of tricks, in fact, has allowed the Greeks to discover the true battle positions of the Communists, which are quite different from what had been assumed. The American who begins to understand the valor of the Greeks is not Pryor, who has become somewhat irrational in his new hatred of Greeks, but a tough working-class corporal played by Lee Marvin in one of his first Hollywood roles.

As Pryor begins to understand how the Greeks have outwitted the Koreans, he recovers some of his respect for the Greeks, yet he is still skeptical about their skills. The new challenge is for the combined platoons to get the data gathered back to headquarters. This is difficult due to technical problems and getting into a position from which they can send a message safely.

The film’s subtext is now explicit. Neither the Greeks nor the Americans can complete their mission and save the day on their own. The platoons must combine their disparate skills. By working in harmony and overcoming distrust, they get the message through to their base commander and what would have been a disastrous defeat becomes a successful UN offensive

Most of the action sequences that follow are standard newsreel stuff designed to show American tank power taking control. Viewers will not be sitting on the edge of their seats wondering about the outcome or whether some major character will be killed. The real battle, the battle to achieve ethnic solidary, has been won. The film ends with the cigarette-smoking Greek American affectionately placing his arm over the shoulders of the pipe-smoking Greek as they are transported from the battlefield by helicopter.

The American forces in the all-male cast contain numerous character actors whose faces will be more familiar than their names. Many of the actors playing Greeks are of Greek heritage. Co-star Alexander Scourby is a Greek American who speaks excellent Greek. Also getting considerable screen time is immigrant Nick Dennis, now most famed for his role as one of the poker players in both the Broadway and Hollywood productions of A Streetcar Named Desire directed by Elia Kazan. The Greek priest is played by real-life priest Father Patrianakos. Other Greeks in the film include Nico Minardos, Costas Morfis, and John Verros.

The Glory Brigade is one of a number of films made in the 1950s in which Greeks are mainstreamed as true Americans. It’s a Big Country (1951), another film about the Korean War offers eight episodes by eight different directors who celebrate American racial and religious diversity. Episode eight features Gene Kelly as Private Icarus Xenophon writing a letter from Korea. In the legendary Kiss Me Deadly (1954), Mike Hammer’s Greek sidekick is played by Nick Dennis. The most ambitious film about Greeks is Beneath the Twelve Mile Reef (1953) in which Greek sponge divers in Florida battle local xenophobes. The film ends with the Greek hero (Robert Wagner) marrying the daughter (Terry Moore) of the leader of the American spongers. Greeks show up as cowboys in genre films like Gunpoint (1955), an Audie Murphy vehicle, and The Silver Canyon (1951), a Gene Autry vehicle. Even more unusual is Tribute to a Bad Man, a film set in the American West of the 1880s in which immigrant Irene Papas sings a love song in Greek to James Cagney.

Even a casual look at how other European ethnic groups were treated in the 1950s would indicate that the framing of Greeks in films like The Glory Brigade was happening with other European ethnic groups as well. Europeans of the Great Migration and their children were being recognized as genuine Americans. It also became proper to accept the increasing need of the American military to work in concert with non-American allies. Neither of those concepts seems very problematic in 2014, but in the 1950s, they represented a fundamental shift in the xenophobia attitudes characteristic of the years prior to World War II.

Dan Georgakas is the author of My Detroit: Growing Up Greek and American in Motor City.

To purchase The Glory Brigade, click here.

Copyright © 2014 by Cineaste Magazine

Cineaste, Vol. XXXIX, No. 3