Cineaste Selects: Forty Years of Favorite Films

To celebrate the 40th anniversary of Cineaste, some of the staff have opted to review a film with a special personal meaning and/or which reflects significant aesthetic, social, or political distinction. The chosen films form a hybrid group that spans the years from 1969 to 1997. The films are presented in no particular order, and cross national and genre boundaries. Cineaste invites our readers to send in reviews of their own favorites, some of which will be chosen for publication as web exclusives when we publish our next print issue. Please send reader reviews to Gary Crowdus at cineaste@cineaste.com or to Cynthia Lucia at cindylucia@aol.com

****

Z (directed by Costa Gavras, France, 1969)

The cover of the 1969/70 winter issue of Cineaste (still spelled with an accent over the ‘e’) featured a scene from Z. Our magazine was then published from offices in the basement of the Bleecker Street Cinema that we shared with Film Society Review. The two magazines worked together harmoniously. In this instance, an interview that Gary Crowdus and I did with Costa Gavras appeared in Cineaste while my review of Z appeared in FSR. Z was a perfect fit for my critical, political, and ethnic sensibilities during those halcyon days of the counter-culture. Having traveled cross-country as a spokesperson for the Greek anti-junta movement, I knew first hand that despite the fervent cooperation of Melina Mercouri, we had not been able to get much attention from the American public or mass media. Z would change that.

The main story line of Z is based on the murder of Gregory Lambrakis, a leftist Member of Parliament, by hoodlums employed by the Greek right. Christos Sartzetakis, identified in the film simply as the Examining Magistrate, vigorously unravels a conspiracy that leads from the killers to the local police and military intelligence and finally to the gates of the royal palace. Although the culprits are successfully prosecuted, an epilogue informs us they were released following a coup by colonels a few years later.

Before seeing the film, I was concerned that it had been shot in Algeria; that Greece was not specifically named as the country in which the events took place; that the dialog was in French; and that the Greek physical presence was limited to Irene Papas in a cameo role. My anxiety proved baseless. By prominently displaying Greek cultural markers, the Greek locale was subtly but unequivocally established. Even better was the music. Mikis Theodorakis had written two new songs for the film, but most of the tunes were associated with the Lambrakis Youth Movement that Theodorakis had founded after the assassination.

The strong script by Jorge Semprum was characterized by his usual complex use of flashbacks. Unlike Rashomon, however, each retelling clarified what had happened rather than presenting reasonable alternatives. Semprun also employed considerable humor. When an anti-Semitic conspirator is indicted, a reporter asks, “Are you the Dreyfuss of Greece? The indignant officer responds, “But Dreyfuss was guilty.”

The great failing I found in the film was that it had not depicted the mass movement that gave Sartzetakis the political space needed for his work. I had been in Greece that summer and witnessed demonstrations throughout the nation. Earlier, nearly half a million Greeks had marched in Lambrakis’ funeral cortege. Gavras agreed with my criticism but explained that he hadn’t had the funds required to show a mass movement and he didn’t think masses of Algerians could have passed for Greeks. He also thought the focus on Sartzetakis, a respected conservative, emphasized the importance of political morality rather than handbook ideology.

Gavras said his filmmaking was a political act. Wanting to bring his political perspective to a mass audience, he had consciously appropriated (or subverted, if you prefer) the Hollywood three-act structure with which the audience was esthetically comfortable. He believed that realism was essential in order to avoid a hagiographic treatment of the martyred Lambrakis and his followers. He further noted that identifying one of the killers as a homosexual was not heterosexual invective. The actual killer had been a homosexual and Gavras wanted to demonstrate how the police had used the man’s fear of sexual exposure to manipulate him. By not emphasizing the Greek aspect of the tale, Gavras hoped to advance the public discourse on political assassinations. Various European critics had so responded, using their reviews to comment on the murders of Ben Barka, Patrice Lumumba, and Robert Kennedy.

After the fall of the junta in 1974, Z was finally shown in Greece where it had a sensational reception. Nearly forty years after its release, I have grown even fonder of the film, marveling that contemporary audiences react to it as intensely as my contemporaries did so many years ago. Z also had an impact on the Cineaste editors. Our conversation with Gavras reinforced our view that interviews that treated filmmakers as artists rather than as celebrities should be part of the evolving Cineaste format. Given the wonderful films Gavras has made since Z, I am particularly pleased with the prophetic words with which Gavras concluded our interview, “I will make more political films. I have a penchant for this kind of film—for films with real subjects.”—Dan Georgakas

Dan Georgakas first become involved with Cineaste in 1969 and has been part of the editorial staff in one or another capacity even since. He is co-editor of Cineaste Interviews and Cineaste Interviews 2.

Pirosmani (directed by Georgy Shengelaya, Russia, 1969)

Bernstein of Citizen Kane saw a girl in a white dress only once and never forgot her. I saw Georgy Shengelaya’s haunting Pirosmani only once many years ago; it made a powerful impression on me, and I never have forgotten it. Unlike Bernstein, for whom not a month went by without thinking of that girl, I recalled the film only now and then, promising myself to catch it again at some festival, or at some indie theater or art house that risked some imaginative programming. And surely I could always locate it on video or DVD. None of that ever happened. But thanks to Cineaste’s 40th anniversary and the Editors’ asking for a contribution to this section, I made an effort to find it, got hold of a video copy, and watched it again. I was not disappointed.

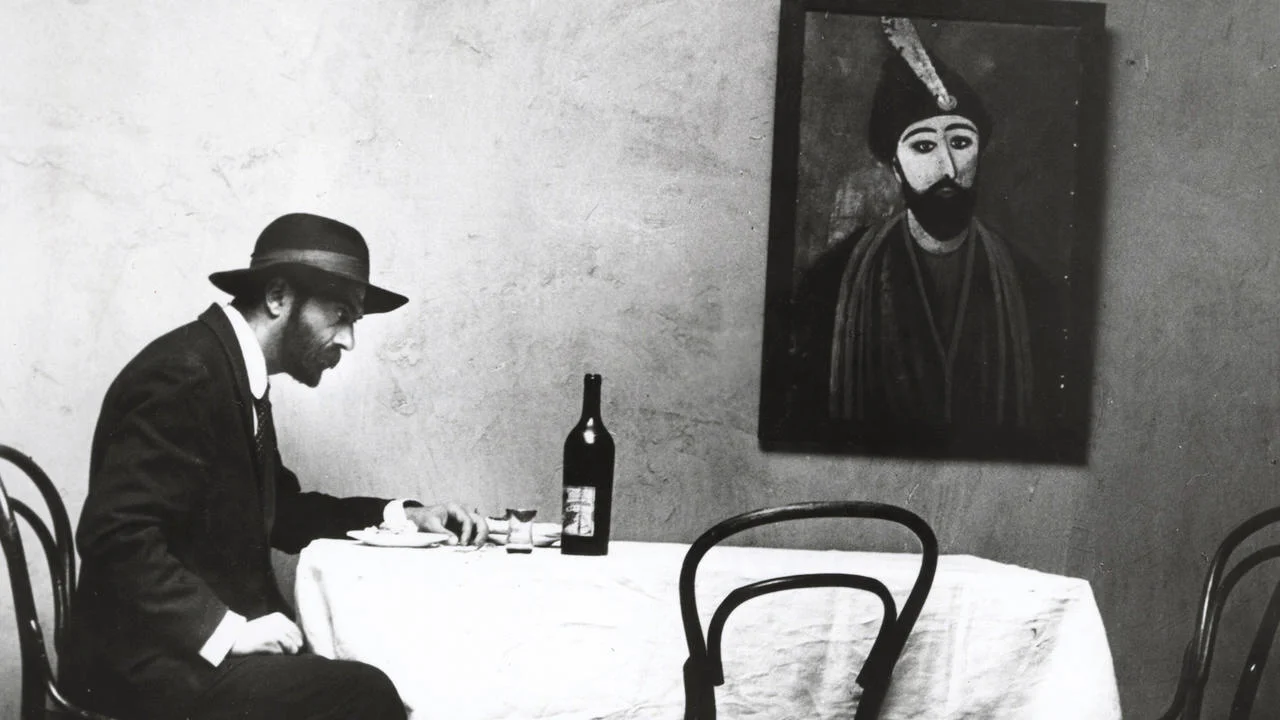

There have been many bio-pics based on celebrated artists, but Shengelaya’s film on the self-taught Georgian painter Niko Pirosmanishvili (1862-1918) is like no other. The same might be said of another Soviet filmmaker’s rendition of an artist’s life—Andrei Tarkovsky’s magnificent Andrei Rublev (1966). Both are unconventional portraits, brilliantly designed, but if Tarkovsky gets it across with a complex and feverishly hypnotic realism, Shengelaya recreates a life by appropriating the paintings themselves, inserting them into the minimalist drama or duplicating them or their likenesses as a series of tableaux vivants. Art (film) imitating art (paintings). Leafing through a volume of Pirosmani reproductions, one sees how closely Shengelaya followed the paintings themselves. The result is a film of enchanting beauty. I can think of only Sergei Paradzhanov’s The Color of Pomegranates (1970), also based on the life of a creative artist, the medieval Armenian poet, Sayat-Nova, as a comparable enchantment.

Pirosmani painted in the flat, primitive style, with odd, subdued coloring and stylized portraiture of people and animals. Shengelaya transfers that style to the film—characters appear in carefully composed and lit interiors or wide-angle exterior landscapes and riverscapes as if they stepped out of the paintings. Wandering in and out of the tableaux is the artist himself, a lonely, aloof, alcoholic and often homeless figure painting sign boards and canvasses in exchange for food and drink at the dukhans (taverns) he frequented in the turn-of-century Tiflis of his native Georgia. Stylized though the plotless inactivity may be, in often enigmatic sequences moving back and forth in time, we do get some sense of the artist’s biography. Shengelaya has used the scanty available documentation to record episodes of Pirosmani’s life—withdrawing from a celebration introducing him to a possible bride; gazing longingly at a music-hall performer, immortalized in his painting of “Margarita;” failing at running a dairy shop because he gave goods away to the poor; uncomfortable at a salon meeting of artists who had discovered his work a few years before his death—when asked to say a few words, he proposes establishing a place with a samovar where artists can gather, drink tea, and converse about art.

From the doleful organ melody played during the opening credits against a dull-green landscape painting on the screen, we know this film and the artist’s existence will be sad. “Stuck,” he says, “in the throat of this cursed life.” In what may or may not be a bow to prevailing Soviet tenets of the time, Shengelaya has Pirosmani express resentment of the rich and well born. At his shop, he charges the wealthy higher prices than the indigent. Someone toasts all the unfortunate who suffer in life. Yet there is a religious undercurrent to the film, which opens with a reading from the New Testament. The closing has a now grey and dying Pirosmani taken from his mean shed on Easter Sunday, as townsmen greet and kiss each other. That doleful organ melody sounds again.

Pirosmani is available for rental in 16mm and 35mm only from Kino International (www.kino.com). I am grateful to Roderigo Brandau at Kino for a video screener of the film. Ruscico will be bringing out a version on DVD, date as yet unannounced (www.ruscico.com). —Louis Menashe

Louis Menashe teaches Russian history and film at Polytechnic University in New York.

Introduction to Arnold Schoenberg’s “Accompaniment to a Cinematographic Scene” (directed by Jean-Marie Straub and Danielle Huillet, West Germany, 1972)

Despite a running time of seventeen minutes, Straub and Huillet’s essay on the social responsibility of artists is, as its title portends, a densely-packed experience—almost shockingly so—and every inch as relevant today as it was in 1972, at the height of the Vietnam debacle. Commissioned by German television for a series of short films on famous composers, Introduction is the very antithesis of PBS bio-schmaltz: a formally rigorous, thematically adventurous, politically scathing, reflexive dialectical argument that unfolds slowly before burning up the screen with the intensity of cinematic napalm. By reputation, and perhaps on cursory viewing, another arid disquisition—lehrstuck—by two monarchs of minimalism, it is instead intensely personal, passionate, and, as a bonus, deserves a place among the greatest Holocaust documentaries.

The pretext, as it were, is a mature 1930 composition by the Viennese maestro—who died in exile in Los Angeles in 1951—which, unlike his other pieces intended for dramatic staging, lacks any directions aside from: “Threatening Danger, Fear, Catastrophe.” There was no filmic ‘scene’ to accompany and, according to Straub, the music is “otherwise unrepresentable.” On one level, then, Introduction is an accompaniment to the “Accompaniment,” a metatextual meditation. It begins in a more or less conventional key: a shot of a Roman fountain (the city adopted in exile by the filmmakers) is succeeded by Straub’s brief on-screen rendering of the musical context. Then three still images of Schoenberg at different stages of his life, over which Straub narrates facts about the composer and augurs his response to a 1923 written invitation from painter Wassily Kandinsky to join the Bauhaus as refuge from the growing persecution of Jews.

Read in long-take excepts by an actor in a recording studio, Schoenberg’s bitter, outraged letters indict Kandinsky’s moral betrayal and his tacit anti-Semitism: “When I walk in the street and all men look to see if I am a Jew or a Christian, I cannot tell everyone that I am the one whom Kandinsky and some others make an exception of, while doubtless Hitler is not of this opinion.” Schoenberg’s composition enters roughly midway through the reading. In shot fifteen—there are thirty-four shots in the film, also “Accompaniment’s” opus number—Huillet is framed in their apartment addressing the camera. Citing Brecht, yet another political exile—and Schoenberg’s fellow Hollywood drone—she prefaces the reading of a 1935 statement linking the rise of fascism with capitalist barbarism. Thus the composer’s humanist moral diatribe is ‘answered’ by Brecht’s materialist historical analysis.

Straub and Huillet perform an act of artistic solidarity; they clearly admire, pay tribute to, and claim the patrimony of both modernist icons. Their film builds to a Brechtian moment of self-scrutiny and is undergirded by principles analogous to Schoenberg’s atonal techniques; for instance, varying lengths of black leader divide most of the shots, making them feel more concrete or syntactically autonomous. In the face of ‘threatening danger,’ neither artist claimed intellectual privilege or isolated his work from Europe’s encroaching political crisis. Determined to follow in their footsteps, Introduction makes a spectacular discursive leap. Archival shots show bombs being prepared in a factory then loaded onto airplanes. For a while it is unclear whether the relevant era is WWII or the Sixties. Then an American plane drops what is unmistakably a load of napalm over a jungle landscape. Straub and Huillet have added another plank to the argument, as if to say: what should we, as artists, be doing now, be creating now?

In a final shift in tone—and visual materials—contemporary German news headlines and the body of a newspaper story announce the recent acquittal of architects who designed concentration-camp gas chambers and crematoria. These men, the anti-Schoenbergs, lent their art to a genocidal regime. With this parting gesture Straub and Huillet challenge not just artists but all of us to consider how our labor is positioned in regard to yet another pack of war criminals savaging in our name and what the personally relevant avenues of resistance might be. Straub called Introduction “the most experimental we ever made.” Certainly its radical heterogeneity, and hard-edged mixture of filmic categories, is part of its message. Pastiche is, as Fredric Jameson observed early on, the artistic emblem of a vapid, ahistorical postmodernism. This tiny gem of a movie is everything pomo is not, and more power to it. —Paul Arthur

Paul Arthur is the author if A Line of Sight: American Avant-Garde Film Since 1965 (University of Minnesota Press, 2005 ) and the forthcoming Nick Broomfield (University of Illinois Press, 2008).

Welfare (directed by Frederick Wiseman, U.S., 1975)

1967 marks the first appearance of Cineaste, and it also marks the first documentary directed by Frederick Wiseman—arguably the most important documentarist in American film history. From that first film, Titicut Follies, through his most recent State Legislature (2007) (reviewed in this issue of Cineaste), Wiseman has continued to weave a complex tapestry of American politics, ideology, and culture through observing its institutions—revealing the humiliating treatment of inmates at the Bridgewater State Hospital for the Criminally Insane in Follies, the exercise of authority in Philadelphia’s North East High in High School (1968), and the arbitrary experimentation at the Yerkes Primate Research Center in Primate (1974), as well as the care and patience extended to children at the Alabama Institute for the Deaf and Blind in Multi-Handicapped (1986) or in a Florida shelter for battered women in Domestic Violence (2001). Whether institutional rules are enacted with eerie precision, as at the Vandenberg Air Force Base in Missile (1988) and the Neiman-Marcus flagship store in Dallas in The Store (1983), or whether people struggle to navigate thorny psychological and bureaucratic terrain, as on Chicago’s South Side in Public Housing (1997), and in Memphis’s Juvenile Court (1973), Wiseman’s camera remains consistently dispassionate, though keenly attuned to the perplexing contradictions, dark ironies, accidental humor, and genuine struggles played out in the various theaters of American life.

Institutional complexity (and chaos) is nowhere more powerfully captured than in Welfare (1975), shot in 1973 at a New York City welfare office, where the overriding impression is of caseworkers and clients equally caught in an incomprehensible quagmire of forms, protocol, and contingencies. In one instance caseworkers discuss a woman, just out of the hospital, whose expected check hasn’t arrived. “She’s a conversion; there’s nothing we can do,” says one, with further instructions that she contact Social Security—a telling revelation of systems so unwieldy they cannot (or refuse to) communicate with each other. In another case a client is told that she will lose her monthly rent allotment of $150 because the apartment she’s living in costs $170. Although the woman offers to augment her allotment with $20.00 from her earnings, the rule remains inflexible—designed it would seem to encourage transience or homelessness. When I interviewed him more than a decade ago (Cineaste, Vol. XX, No. 4, 1994), Wiseman observed that in a system serving millions of people “rules and regulations are necessary;” his camera here, however, captures an absurdity with life-defeating consequences. Racial tensions surface in one scene as a frustrated Vietnam veteran proclaims, “I’m getting a 357 magnum and blowing every black I see out of existence,” a line that resonates starkly in a later scene when several children play in a waiting room, using umbrellas as rifles. People wait; the camera watches; frustration, anger, and feelings of helplessness grow.

Although adopting the observational mode common to all of his documentaries, in Welfare Wiseman uses frequent sound bridges in order, he said, to indirectly “raise the question of resources” but more importantly to show the absence of privacy, “the State in relation to the people.” Among the most compelling moments is one in which several clients address the camera directly—a rare occurrence in Wiseman films, where the camera remains unobtrusive and unacknowledged. “I can show you so much stuff,” one man proclaims, pulling papers and more papers out of his pockets, as another man addresses the camera saying he needs to mail letters but has no stamps. Is he asking for a handout or is this just one more expression of powerlessness in the face of a system so Byzantine in its bureaucracy? It seems the latter, as echoed in darkly ironic shots of file drawers stuffed, a caseworker flipping through books of forms while surrounded by towers of paper, and a computer spewing out more and more tapes and forms—not quite Kalfka, but close, as the camera sustains its gaze, refusing to waver from this interminable scene of bureaucratic replication.

Like so many of his films, Welfare takes us into bowels of the system, showing us that “it’s not easy,” as Wiseman modestly has pointed out. Perhaps he is implicitly answering critics of direct cinema, as well, suggesting that a more conventional form, providing contextualizing detail and proposing possible solutions, would be hopelessly naïve.—Cynthia Lucia

Cynthia Lucia is an Assistant Professor at Rider University and the author of Framing Female Lawyers: Women on Trial in Film (University of Texas Press, 2005).

Taxi Driver (directed by Martin Scorsese, U.S., 1976)

Taking another look at Taxi Driver, one discovers ambiguities giving its portrait of the city even greater power and resonance. Taxi Driver also demonstrates how much Scorsese has sacrificed in personal style and vision when directing his recent big budget, commercially successful entertainments.

In a film like Mean Streets (1973), Scorsese’s Italian-American community may have been largely criminal, but it was an ethos with a set of codes. But driving through the center of the night city carrying “bad ideas in his head,” Taxi Driver’s Vietnam vet, Travis Bickle (Robert De Niro), is more alienated than any of the Italian-American ‘boys.’ Though on the margins, they are an indivisible part of a subculture; whereas, Travis has no church, family, or male buddies to give him solace.

There are no Italian street festivals in Taxi Driver’s New York. It’s the nightmare city where police sirens wail, steam rises from manhole covers, open hydrants spurt torrents of water into garbage-filled gutters, prostitutes in hot pants avidly troll for customers, and madmen shout wildly into the darkness. Travis drives through the desolate night streets, his cab window pelted with eggs, and a stop at a bodega leading to his casually killing an armed robber. The city is out of control, and the oppressive summer humidity and heat conveys the sensation of a rotting, rancid universe.

Although Scorsese sees New York of the Seventies as radiating “a constant sense that the buildings are getting old, things are breaking down” and “society is in a state of decay,” his nightmare city remains seductive. Scorsese loves his New York locations, and feels that the grandeur and energy of the city at night could not be matched by any other city in the world. Taxi Driver’s urban hell, then, conveys its own brand of splendor.

Scorsese is not interested in providing a social or political critique of urban anomie and squalor, nor does he view the behavior of the underclass as socially determined—transforming them into victims of poverty, racism, or brutal, abusive childhoods. Scorsese even finds that the rodent-like Sport (Harvey Keitel) is capable of some manipulative tenderness towards Iris (Jody Foster), the fourteen-year-old prostitute he exploits. The debased life is never romanticized, but what he offers her provides as much or as little joy as the world offered by her ‘ordinary folks’ back in Pittsburgh. While Travis may see Sport and the street people as animals fit only for “flushing down the toilet,” Scorsese, in turn, never judges them, but sees them as part of New York’s texture.

Though never clearly delineated, Travis and Scorsese’s perspectives are not identical. Yes, Travis may see the city as an “open sewer,” but he’s also attracted to its streets. While Scorsese’s fluid, soaring camera movement and formally rich mise-en-scene gives us an unsentimental look at urban ugliness that always remains aware of its aesthetic possibilities.

Taxi Driver owes much more to film noir than to social realism. And despite several neo-verite scenes, most of the film feels like a slice of delirium—a selective, subjective view of a city where the balance between the hallucinatory and the ‘normal’ has tipped. Scorsese’s vision of the city is more darkly radiant than most of the works of film noir. Even in the aftermath of Travis’s bloody slaughter of Sport and his thug associates, the dimly lit, East Village tenement is stylized, and turned into street theatre. Slow motion and an overhead crane shot—as police, ambulance crew, photographers, and neighborhood people crowd the sweating street—replicate the look of tabloid Weegee photos.

Scorsese’s New York is clearly a darker, more dangerous city than the glistening, safe one of Woody Allen films like Manhattan, shot during the same period. But there is a part of Scorsese’s sensibility that embraces its sordidness. Scorsese’s New York glows in its meanness and peril. In the words of Baudelaire, he has transformed it into a metropolis, “whose hellish charm resuscitates.”—Leonard Quart

Leonard Quart is a free lance writer and Professor Emeritus of Cinema Studies at COSI and at the CUNY Graduate Center. He has co-authored with Albert Auster American Film and Society Since 1945 (Praeger, 2001).

One Man’s War (directed by Edgardo Cozarinsky, France/West Germany, 1982)

Rarely revived—and never available on either VHS or DVD—Edgardo Cozarinsky’s La Guerre d’un seul homme/One Man’s War—is one of the most historically incisive and esthetically daring (as well as one of the unjustly neglected) documentaries of the last forty years. How can one account for this film’s relative obscurity? Although Cozarinsky’s film deals with one of the most traumatic episodes in twentieth-century history—the Nazi occupation of Paris—it includes none of the sensationalist violence that usually accompanies Hollywood (or even the slicker European) films that take on this era. And unlike an equally estimable documentary which addresses the same subject—Marcel Ophuls’s The Sorrow and the Pity—One Man’s War does not even flog a controversial, easily summarizable thesis.

Yet this almost unclassifiable documentary—a found-footage movie and essay film with literary and political resonance—is far from innocuous. While Ophuls’ seminal film explicitly challenged what political scientist Stanley Hoffman once termed “the mythology of the French Resistance”—the erroneous assumption that France was completely united against Nazism during World War II with the exception of isolated collaborators—Cozarinsky more subtly undermines that myth through an extremely oblique and unorthodox modus operandi. Pascal Bonitzer of Cahiers du Cinéma labeled this film’s conception of documentary “archival montage.” Found footage of the German occupation—primarily Nazi and Vichy propaganda newsreels—are interwoven with diary recollections of contingent events recorded by the German novelist and essayist Ernst Jünger (read as voice-over on the sound track by the actor Niels Arestrup). The often-ingenious aural and visual juxtapositions employed by Cozarinsky do not, however, possess the visceral frisson of Eisensteinian montage.

Jünger himself is a literary figure who inspires extreme ambivalence, since appreciation of his often-beautiful prose is tempered by disgust for his frequently repellent political convictions. He is usually considered part of a group of conservative intellectuals opposed to the ‘liberal’ tenets of the Weimar Republic. Although Jünger’s idiosyncratic conservatism was somewhat different from mainstream National Socialism (never officially a Nazi, he attacked Hitler for his “parliamentarianism” in the early Thirties), he served as an officer in the Wehrmact during World War II and was considered a suspect figure by leftist critics during his long postwar literary career. On the other hand, as the film informs us, by 1933, Jünger became “disgusted by Hitler’s interest in his work,” and Cozarinsky believes that one of the most writer’s most celebrated early novels, On the Marble Cliffs, can be deemed a prescient “allegory of Nazism.”

Much of the cumulative power of One Man’s War resides in the collision of Jünger’s icy introspection and the frequently chilling (although also occasionally banal) events chronicled in the meticulously chosen archival footage. For example, a shot of a marquee advertising Veit Harlan’s anti-Semitic film, The Jew Süss, is the catalyst for Jünger’s strangely emotionless account of wooing an adolescent girl he encounters in Monmartre. A more serious type of moral hibernation becomes evident in a sequence of the film that focuses on Jünger’s trepidation as he prepares to execute a deserter. Footage of German soldiers mingling with an exultant crowd and a brief shot of a pensive Hitler precede the author’s calm admission that “I’m assigned to supervise the execution of a deserter . . . it would have been easier to call in sick.” Despite the slightly shocking lack of affect that is such a vital component of Jünger’s anecdotal style, his passivity seems to take on an air of melancholy integrity in the context of newsreels documenting the Vichy chief of state Marshal Petain’s popularity, footage Cozarinsky intercuts with this remarkable fragment of self-revelation.

Even the music on the soundtrack of One Man’s War offers a subtle riposte to the official ideology Jünger was obliged to pay obeisance to—despite his unarticulated qualms. Cozarinsky’s choice of music reflects a conscientious policy of ‘race mixing.’ To invoke the Nazi regime’s pseudo-scientific esthetic distinctions, the film intermingles the ‘Aryan’ music of Richard Strauss and Hans Pfitzner with the ‘degenerate’ music of Jewish composers Arnold Schonberg and Franz Schreker. (Although only half-Jewish and raised as a Catholic, Schreker was still a victim of Nazi anti-Semitism.)

If One Man’s War has any cautionary lessons to impart, they are not reducible to easily consumable bromides. Yet the blatant gap between private anguish and public inertia that becomes all-too visible in Jünger’s diary entries remains pertinent to our own era of burgeoning confessional literature and diminishing moral courage.—Richard Porton

Richard Porton is currently editing a volume on film festivals for the Wallflower Press’s Dekalog series.

Used Cars (directed by Robert Zemeckis, U.S., 1980)

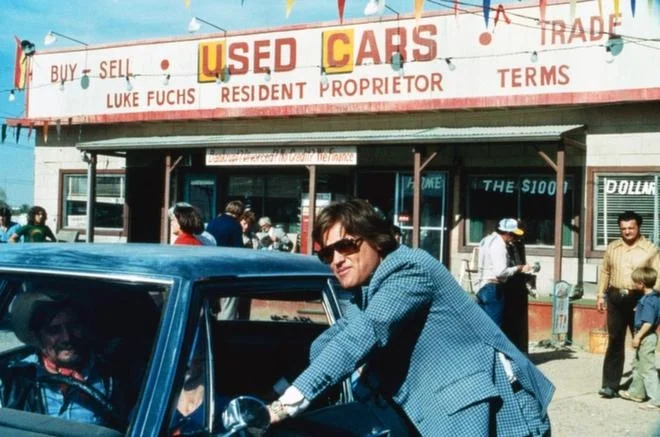

Feebly marketed as a Smokey and the Bandit-type action comedy in July 1980, then abandoned as roadkill, Used Cars came roaring back to life on HBO less than a year later, which is where I saw it, again and again. In the pre-home video era, pay cable was a godsend, transmitting hard-to-see films like the original Assault on Precinct 13, Mad Max, and Over the Edge to Variety-reading cineastes like myself who were too young to drive. (It’s hard to imagine today’s high school kids avidly discussing The Tin Drum the day after it aired, but we did—mostly the nudity.) For me—and for Pauline Kael, who as I recall also caught up with it on HBO— Used Cars was the great discovery, a movie that grabbed me by the funnybone and never let go. It’s been available on DVD since 2002, with a boisterous commentary track by its never-better star Kurt Russell and co-creators Robert Zemeckis and Bob Gale. Back then, however, if it aired at 2 a.m., and I wanted to watch it, I was up through the graveyard shift. Used Cars is my personal definition of Kael’s “movie love.”

A recap—for the uninitiated. The film centers on twin used car dealers in the Phoenix area, gentle, grizzled Luke Fuchs, and his slicker, nastier brother, Roy L., both played to perfection by Jack Warden. When Roy L., the owner of the fancy Auto Emporium, learns that the city fathers plan to construct a new freeway ramp on his property (“It used to be that when you bought a politician in this country, that son-of-a-bitch stayed bought!” he roars), he schemes to get his hands on Luke’s crumbling New Deal lot across the street, which will be a goldmine with all the traffic coming through. In one of the movie’s funniest scenes (“Fifty dollars never killed anyone!”) Luke is bumped off, but New Deal is strengthened by its brazenly conniving employees, salesman and aspiring Senate candidate Rudy Russo, with his “Trust Me” bumper stickers (Russell), superstitious salesman Jeff (the live-wire Gerrit Graham), and strong-arm mechanic Jim (Frank McRae). They secretly bury Luke’s body on the lot—“Chrysler, Ford and GM will be your headstones,” says Rudy, by way of last respects, in a mock-funeral scene parodying the cinema’s Ford, John. Keeping the bad news from his guileless daughter Barbara (Deborah Harmon), they continue to bluff Roy L. and his cronies, while drumming up business with outrageous pirate TV ads, one of which breaks into an address by then-President Carter. Zemeckis comments on the DVD that executive producer Steven Spielberg was scandalized by the juxtaposition of footage of the president with New Deal’s raunchy spot, but, as Rudy explains in the film, “he (the president) fucks around with us, why can’t we fuck around with him?”

Used Cars fucks around with a lot of American sacred cows. Everyone is on the make, or on the take, and greed keeps the political machine well-oiled. The old West of Ford and Hawks is dead as a literal New Deal languishes; the cowboy has been replaced by the huckster; and the cattle drive is swapped out for a rally of 200 rat-trap automobiles, which barrel through the Arizona desert to save the day for the marginally-less-mendacious good guys. (The writers connect the dots on their screwball plot with airtight precision; the film, smartly edited by Spielberg’s cutter Michael Kahn, is a model of comedy construction, with the great, caustic, coherent script that W.C. Fields never really had.) During the commentary, Russell calls that characters Rudy and Barbara, who learn to go with the flow of deceptions, “Bill and Hillary in training”—an interesting observation, but too specific. We’ve all had this kind of training in the back-stabbing, glad-handing side of the American way, and it’s gratifying to see a movie that revels in its comic possibilities while telling it like it is.

Then as now, I love Used Cars because it makes me laugh. The supporting cast, including Joe Flaherty, Dub Taylor, and Al Lewis, is tip-top. Toby, Jeff’s accomplice mutt, is one of the best dogs in movie history. The elaborate car stunts are zestily executed. The DVD identifies Used Cars as “from the director of What Lies Beneath, Forrest Gump, and Cast Away” but that’s the safely middlebrow Zemeckis who joined the Auto Emporium once he and Gale hit it big with the Back to the Future trilogy. I preferred him when he was wallowing in the muck of the New Deal lot, and so will you, if you take Used Cars out for a spin. Trust me.—Robert Cashill

Robert Cashill blogs at Between Productions.

Blue Velvet (directed by David Lynch, U.S. 1986)

With Blue Velvet, a mystery thriller set in Lumberton, North Carolina, David Lynch joined the ranks of great American filmmakers, like Welles and Hitchcock, who built their cinema on irresolvable tensions between vision and the politics of Hollywood commercialism. His earlier films had led to this development by permitting him to hone his personal style and learn the art of self-defense in the mainstream media. After his first film, Eraserhead (1977), Mel Brooks labeled him the first genuine American surrealist filmmaker, made him the director of The Elephant Man (1980), and protected his decisions, even though Lynch didn’t have contractual creative control. With Dune (1984), Dino DeLaurentiis taught him the necessity of the right of final cut. With Blue Velvet, Lynch began to take on Hollywood on his terms.

While telling a story with many generic romance and mystery elements, Lynch took issue with recipe filmmaking from the first frames of Blue Velvet—with darkly undulating blue draperies which form a backdrop for the romantic, pristine white font of the credits, while the dissonant yet melodic main title theme plays—to the partly comic, complex closure which blends a version of Hollywood’s happy ending with a malaise about what continues to lurk under the surface. Blue Velvet offers an altered form of spectatorship that pulls two ways: into the familiar acquiescence to Hollywood’s reassurances about boy meeting girl, and outward toward a dream-like distance from which we see and/or intuit the darkness behind such reassurances. Protagonists Sandy (Laura Dern) and Jeffrey (Kyle Maclachlan), who defy the warnings of Sandy’s police detective father and successfully investigate drug dealer Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper), are Peyton Place ingénues–and they aren’t. “I don’t know whether you’re a detective or a pervert,” Sandy tells clean cut Jeffrey. “You’re like me,” the degenerate Frank tells him. And both Jeffrey and Frank are equally drawn to Dorothy Vallens (Isabella Rossellini), a masochistic night club chanteuse. In fact, the clichéd ‘good’ men of Lumberton all have their ‘Frank moments.’ American constructions of masculinity are under the microscope here when Lynch plays with our movie stereotypes, as are the structures of law, morality, art, and even our perceptions of physical reality. Thus the closure, in which Jeffrey sorts out his resemblances to and differences from Frank, may satisfy conventional, rational expectations; but it doesn’t put a dent in the larger mysteries Lynch conjures. Lynch complicates the moment when the ‘bad guy’ gets his, by continuing to point beyond Frank’s death toward multiple planes of reality and irrevocably tangled skeins of human identity.

Was Brooks correct about Lynch, and has Lynch since used his creative control to sow in mainstream filmmaking the seeds of an American surrealism? The matter is up for debate. Although Lynch is more anchored in the materiality of the world than Salvador Dalí and Luis Buñuel, a materiality he senses is often blocked by social constructions, he and the surrealists do share a common interest in the subconscious and in creative dissonance, and Blue Velvet was pivotal in his administering of injections of these elements into American popular culture. Unhappily, for every Jim Jarmusch who has experimented in a dynamic, organic way with Lynchian discontinuities and altered perceptions, there are a dozen commercial hacks who have imitated Lynch’s surfaces to produce ersatz window dressing for tired generic narratives, as in the films of Ron Howard and in trivially quirky television series like David E. Kelley’s Picket Fences.

Critical refusal to confront Lynch’s evocation of the fraught interconnection between reality and social habits of mind has led to other forms of irrelevance and triviality. Slavoi Zizek stares at his own image in his neo-Lacanian mirror instead of looking at the films. Others have trivialized Lynch’s work in interpretations that misread into them a politically reactionary bent and gimmicks. But others have taken an arguably more productive perspective that embraces Lynch’s visionary play with established narrative and visual markers. Decades ago, feminist and Marxist critics paid Hollywood a high compliment in their against-the-grain readings, which probe the power of film to influence the way America constructs gender and class. In Blue Velvet, Lynch assumed a role—which he has continued to play—of director-as-reader-against-the-grain, going beyond feminism and Marxism toward the creation of a cinema that taps into the emotional power of conventions and simultaneously suggests how rigid formulas foment an alienation from the world we might more joyously inhabit. –Martha P. Nochimson

Martha P. Nochimson is the author of The Passion of David Lynch: Wild at Heart in Hollywood (University of Texas Press, 1997). Her most recent book is Dying to Belong: Gangster Movies in Hollywood and Hong Kong (Blackwell, 2007).

A Moment of Innocence (directed by Mohsen Makhmalbaf, Iran, 1996)

Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s A Moment of Innocence combines the art and politics of the movies like no other film. Makhmalbaf uses the film as a way to revisit a defining moment in his life, when as a young Islamic radical, opposed to the Shah, he stabbed a policeman in an effort to take his gun. Now, years later after the Islamic revolution, Makhmalbaf revisits this crucial moment from his past and tries to imagine the incident not only from his own perspective, but also from that of the policeman. The film is about the process of recreating this moment and becomes not just a reflection on the director’s past, but an examination of the ability of cinema to reveal the truth and an examination of the dynamics of recording history.

As the film begins, the power relationships of the past are reversed. The policeman (Mirhad Tayebi) appears at Makhmalbaf’s door in the hopes of being cast as an actor. Makhmalbaf’s daughter dismisses him as one of many strangers who come to the door looking for a break; she even leaves the humble gifts he has brought outside the house. Eventually the policeman gets a hold of the director and the film begins production. The policeman wants to play himself as the young man he was when the incident occurred, but is finally convinced to participate in the casting of a younger actor. He picks a handsome, urbane young man, rather than a plainer looking boy with a similar small-town background. Makhmalbaf nixes his first choice and forces him to cast the other boy. Of course, Makhmalbaf is free to choose anyone to play himself as a young man and he casts an idealistic, handsome boy as his alter ego. It seems as though the victors are writing the history. One of the film’s great mysteries is that Makhmalbaf’s intentions are never plainly presented, although he displays equal measures of egotism, good humor, and perspective about his past.

Each man is left on his own to direct his younger self and fill in the background to the story. The policeman teaches his ward how to march, wear a uniform and stand at a post. He explains that he was distracted on the day of the stabbing because he had fallen in love with a girl who passed him each day. When young Makhmalbaf approached him, he was more concerned about having failed to present her with a flower than protecting himself. The policeman’s motivations are grounded in the material. He is earning a living, thinking about a future marriage. Makhmalbaf, on the other hand, is full idealism and schemes. He is in love with his cousin and the two of them dream of saving the world and plan to disarm the policeman so that they can rob a bank and fund their ambitious plans. The director and young counterpart visit the cousin, now married, with the intention of casting her daughter. No longer an idealist, she seems impatient with the whole notion and refuses to allow her child to participate. Another girl is chosen instead. While Makhmalbaf and his cousin talk, her daughter slips out to the car and suddenly falls into character as the young revolutionary, but only for a minute before she is called back to the house. We hear the daughter complain bitterly over her confinement as the two men drive away and Makhmalbaf briefly suggests that there are new struggles to be fought in his country.

Once the casting is complete, the actors and directors practice the movements and events that lead to the final confrontation. The film’s editing is deceptive as we realize that events that seem to be happening in sequence are actually happening simultaneously. Characters and scenes begin to overlap as the crucial moment nears. The fluidly mobile camera follows the actors through the ancient corridors of a covered bazaar and into the snow-covered pavement of modern Tehran. The old and new of the city parallel the way in which the film brings past present together. We learn that all was not as it appeared for the policeman with a stunning poignancy. Makhmalbaf is able to transcend the clever self-reflexivity of so many art films and find within it a powerful and profound way of presenting the past and his story. We easily accept that this act of what can only be called terrorist violence is a moment of innocence, yet we are left to ponder whether it is the assailant’s or the victim’s innocence to which the title refers.—Rahul Hamid

Rahul Hamid is a doctoral candidate in Cinema Studies at New York University and writes and teaches on varied topics in international cinema.

Jackie Brown (directed by Quentin Tarantino, 1997, U.S.)

Before Quentin Tarantino went for baroque, he was classical. In the 1990s, the geek-savant of independent cinema romanced three gems of the urban crime genre: Reservoir Dogs (1992), Pulp Fiction (1994), and Jackie Brown (1997), ADHD-addled updates besotted with Hollywood craft and New Wave flash, a l’amour fou the likes of which had not been seen since Truffaut, Godard, and Chabrol squabbled over Howard Hawks in the lobby of Cinematheque Francaise. A second generation auteurist, Tarantino was lucky enough to hit filmic puberty during the literate peak of the second Golden Age of Hollywood in the 1970s, promiscuous enough to stalk the drive in as well as the art house, and diligent enough to vacuum up what he missed on video. More than the avatar of the indie breakthrough into the corporate big time, he embodied a one man renaissance.

Of the trilogy, Jackie Brown gets the heaviest rotation on my personal DVD playlist. Like the job-of-work professional who is its moral center, Tarantino seems unhassled and unhurried, almost serene, relaxed at the plate and graceful on the field, no longer fearful about getting tossed out of the line up or obliged to blast one out of the park, just a reliable clean up hitter who can deliver a stand-up double on demand. It is a batting stance he has yet to recapture.

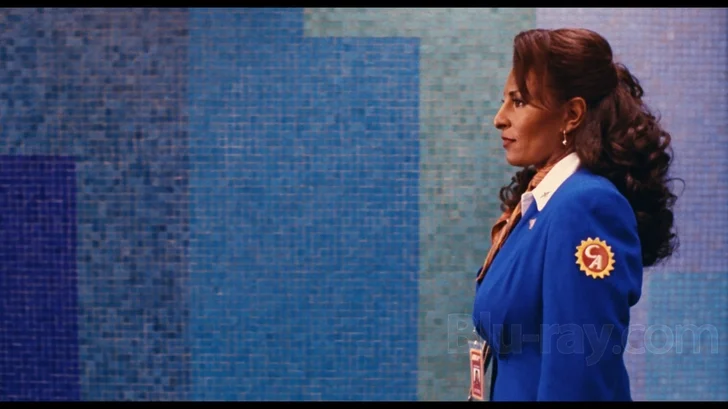

Elmore Leonard, the gold standard for pulp fiction, blueprinted the plot that even by the standards of noirish heist double crossing crime mellers is seriously convoluted. When the well-preserved flight attendant Jackie Brown (Pam Grier) gets busted at LAX for smuggling cash and coke for the gunrunning Machiavellian Ordell Robbie (Samuel L. Jackson), she knows that the lethal occupational hazard will not be the eager-beaver ATF agents rifling through her carry-on. (Michael Keaton later reprised his role as hyperkinetic treasury agent Ray Nicolette in Steven Soderberg’s Out of Sight (1997), another Elmore Leonard adaptation, an absolutely delightful intertextual cross pollination.)

Ordell is a verbally deft, utterly merciless sociopath whose posse includes taciturn ex-con Louis (Robert DeNiro), leggy surfer girl Melanie (Bridget Fonda), and ratchet jawed gunsel Beaumont (Chris Tucker), a liability with a short life expectancy. To maneuver Jackie into target range, Ordell hires the world-weary bail bondsman Max Cherry (Robert Foster) to spring her from jail. No sojourn in an LA lock-up can make Jackie look un-Foxy: one spellbound look and Max sees if not a love connection than at least a kindred spirit. In the elaborate bait and switch Jackie concocts to out-fox both Ordell and the ATF, Max knows she’s playing him, but he’s bemused and enchanted rather than resentful, and we know just how he feels.

Throughout the serpentine shenanigans, the then-thirty something Tarantino shows an unexpected affinity for the hard-won self knowledge, limited options, and sheer calloused competence that comes with late middle age: Max owning up to his hairpiece without shame, Jackie knowing she’s bottomed out, a prospect “that scares me more than Ordell,” and even the cagey psych-out artist Ordell, who is very good at looking out for Ordell. No punk himself, the allegedly young Turk director pays due homage to his elders by resurrecting two faded actors from the 1970s, Grier and Foster, as the late-blooming nearly-lovers.

Of course, Samuel L. Jackson is a hoot to harken to, slinging the n-word and his trademark twelve-letter benediction like Olivier wrapping his tongue around a Shakespearean soliloquy. “The AK-47—when you absolutely, positively have to kill every motherfucker in the room,” he brays during a promo video for automatic weapons (“Chicks with Guns”—available in its bikini-clad entirety as a DVD extra). When Max asks Ordell if his place of residence is a house or an apartment, he savors the comeback. “It’s a house,” he says, the slick gangsta from the hood suddenly the proud bourgeois home owner. In outrageously matching attire, menacing and magnetic, he is a slithery charmer who does not need a wallet saying “Bad Motherfucker” to know he is one.

For the soundtrack, QT the deejay racks up a mix tape from a dream jukebox: Bobby Womack’s majestic “Across 110th Street,” from the eponymous 1972 blaxploitation flick; the syrupy Philly soul of the Delfonics, which Jackie plays for Max on her symbolically retro vinyl collection; and, unforgettably, the eerie, echo-chamber strains of “Strawberry Letter 23” by the Brothers Johnson as Ordell drives Beaumont on a long-take dead end. (What is it with Tarantino car trunks?)

In a commentary clip on the DVD release, Tarantino likens Jackie Brown to Howard Hawks’ Rio Bravo (1959). “A hang out movie,” he calls it, meaning that the intricately layered plot is a distraction the first time around, that one comes back to the film to hang out with the characters and drink in their personalities—to share a quiet cup of coffee with Jackie and Max, sip drinks with Ordell and Louis, smoke a bowl with beach bunny Melanie, and, not least, to bathe in the creative glow of a white hot talent at the top of his game. –Thomas Doherty

Thomas Doherty is Professor of American Studies at Brandeis University and the author of Hollywood’s Censor: Joseph I. Breen and the Production Code Administration (Columbia University Press, 2007)

Copyright © 2007 by Cineaste Magazine

Cineaste, Vol. XXXII, No. 4