Battle in Seattle: An Interview with Stuart Townsend

by Andrew Hedden

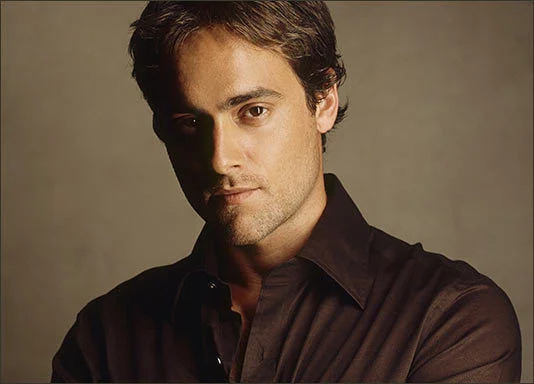

Stuart Townsend

On November 30, 1999, another cold, gray, and wet day in Seattle, Washington was transformed into a date in history. A broad network of 50,000 organized demonstrators, representing the concerns of labor, environmentalists, the global South and many others, effectively shut down the ministerial of the World Trade Organization. Police responses quickly spun out of control, and the National Guard was called in as the protests continued for several days afterwards.

The protests brought to a head in the United States what had been simmering for decades globally. As profits plummeted in the 1970s due to increased competition between capitalist countries in the global North, politicians and corporate policy-makers sought new paths to profits. Under the banner of “neoliberalism,” they developed an ideology that demanded governments the world over privatize social services, repeal regulations of the economy, and submit to the turbulence of a globalizing free market.

The World Trade Organization emerged as one international institution tasked with putting neoliberalism into practice, negotiating broad free-trade agreements between its member nations, and overruling individual governments’ laws as barriers to free trade. Often, these laws represent environmental protections and labor rights, a point the protests in Seattle and elsewhere have sought to underscore. The Seattle protests in particular emboldened delegates in the global South, who have accused countries in the global North of pushing globalization without opening their own countries to the same policies. The result has been increasingly deadlocked talks, making the organization’s prospects for the future quite dim; world-systems analyst Immanuel Wallerstein, for one, has declared the WTO “effectively dead.”1

The Seattle protests proved resistance to the WTO could be as global as capital. While the protest occurred in the final days of the twentieth century, it was very much a twenty-first-century event, quickly transmitted all over the world in images by mass media. With Irish actor Stuart Townsend’s new film Battle in Seattle, his first as a writer and director, the events of N30 (as it came to be known in the global justice movement) stand poised to be widely transmitted once again, this time as a dramatized feature.

Battle in Seattle is not a film about global trade policy, at least not directly. Today, when the WTO itself is much less a world force than it was ten years ago, Battle in Seattle not so much addresses the WTO itself as it seeks to foreground the fierce debates in the streets in 1999. A short documentary-style introduction gives a history of the WTO at the beginning of the film, but by the twenty-minute marker the protests are well underway.

Not unlike the global justice movement it draws its inspiration from, Townsend’s film seeks strength in its diversity, reenacting the events of the Seattle protests through the eyes of no less than a dozen characters. These include a cross-section of protest organizers, including the direct-action activist Jay (Martin Henderson), the anarchist Lou (Michelle Rodriguez), and the endangered-turtle-costume-wearing environmentalist Django (Andre Benjamin). Their stories are told in tandem with the stories of the many whom their protest activities are affecting, including the city mayor (Ray Liotta), an African delegate (Isaach De Bankolé), an NGO representative (Rade Serbedzija), and rank-and-file cop Dale (Woody Harrelson), whose pregnant wife Ella (Charlize Theron), a department-store clerk, gets caught in the ruckus in the downtown streets.

In attempting a discordant synthesis of perspectives, according sympathy to each character it draws into its narrative, Battle in Seattle is an ambitious work. It is especially rare in giving sympathetic treatment to characters not often seen in major motion pictures, namely political activists. It is particularly uncommon for such a politically-charged film to attempt to activate audiences, not through persuasive or factual argument as in a documentary, but through a compelling story. In this it follows in the tradition of filmmakers like Costa-Gavras. Among American filmmakers, it has less precedent, but certainly follows in the tradition of such works as Haskell Wexler’s Medium Cool (1969), a film that Townsend has continually cited in interviews, and a brief clip of which appears in Battle in Seattle itself.

Townsend’s debt to Medium Cool is largely one of content. Not unlike Stephen Marshall’s little-seen Medium Cool remake, This Revolution (2005), Battle in Seattle draws from Cool’s coverage of large protests (in Cool’s case, the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago), but disregards its more daring cinematic elements. Whereas Wexler self-consciously patterned his film after the then-ground-breaking works of Jean-Luc Godard, employing nonnarrative editing, nonsynchronous sound, poetic imagery, and a healthy dose of self-reflexivity, Battle in Seattle’s style is more directly indebted to the melodrama of Ken Loach, or the political action cinema of Paul Greengrass. Indeed, serving as Battle of Seattle’s cinematographer is Barry Ackroyd, a longtime Loach collaborator, and also director of photography on Greengrass’s United 93 (2006).

While perhaps not as impressive an achievement as the WTO-protest documentary This Is What Democracy Looks Like (2000), which was shot by over one hundred media activists, Battle In Seattle is in itself an impressive achievement in editing, weaving together a disparate ensemble of characters with the narrative tools of melodrama and action. In many ways, it was the same combination of elements that brought Paul Haggis’s Crash (2004) a great deal of mainstream success. Like Crash, Battle in Seattle is also susceptible to the charge that these very narrative tools turn didactic and contrived when put to a broad political task. In its effort to humanize its every character, address a large audience, and be entertaining to boot, Battle in Seattle ’s exposition of the issues is spread thin, forced to reduce complicated politics to sound bites to fit them within its relatively brief ninety minutes.

It is a paradox that parallels the protests themselves. As explained best in Kristine Wong’s postprotest essay “Shutting Us Out: Race, Class and the Framing of A Movement,” national activists and NGOs who descended upon Seattle for the protest were so concerned with projecting a message of what they presumed to be mass appeal that Seattle organizations of working-class people and people of color were never given a particular voice, leaving local organizers short-shifted.2 Similarly, in Battle in Seattle, each theme may be presented so broadly that it never touches the particular chords it should. In response, at least one protest organizer, David Solnit, has already sought to pre-emptively remedy any misunderstandings of the events with the Web-based project RealBattleInSeattle.Org.

Where the WTO protests lacked for local connections, they no doubt made up for in audacity, and were ultimately, by most accounts, inspiring and powerful for all people seeking a better world. Battle in Seattle may yet prove the same with its audiences—and as Stuart Townsend explains in the following interview, inspiration is clearly his intention. In July 2008 via phone from his home in Los Angeles, Townsend candidly shared with Cineaste his extensive research, the ensemble nature of the film, his cinematic influences, and his ultimate intention to move a new generation of activists.

Cineaste: How did you come to write and direct the film? What initially attracted you to the subject?

Stuart Townsend: When I first came across the story in 2002, I was reading this book called Take it Personally, which is about globalization. There was an essay in there by Paul Hawkens called “The Battle in Seattle.” It was an essay on the event and there were a couple pictures along with it. Those pictures really grabbed me. They were pictures of protest. I wasn’t really that political or familiar with the world of protest, and the creativity and color of it really struck me, and the fact that it got crushed by the police state.

I had never seen that on film before. There have been moments in films with riots, but not a whole film, a whole world. In researching the event, I thought it would be a real chance as a filmmaker to play with montage, to play with docudrama style, and to be more conventional with the interior scenes, shooting more conventionally with tracking shots. The blending of real footage with shot footage, as a first-time filmmaker, that was really exciting to try to do all these things.

Cineaste: What other books and research did you consult for your script and for the film?

Townsend: There’s a huge list. I think I started off with Naomi Klein’s No Logo, and then a lot of the mainstream books. Noreena Hertz’s Silent Takeover, Jagdish Bhagwati’s In Defense of Globalization, Joeseph Stiglitz’s Making Globalization Work , Paul Hawkens Blessed Unrest, Vandana Shiva’s Earth Democracy, Alexander Cockburn’s Five Days that Shook the World . There was also a book called The Battle in Seattle, and another called The Battle of Seattle. They were both excellent books. There was also “Net Roots and Net Wars,” a study done by the Rand Corporation on the tactics of the protesters because they were so successful, how this bottom-up structure actually defeated a top-down hierarchical police structure. Plenty of reading.

Cineaste: You coproduced the film. What was your experience in financing?

Townsend: Every part of the process is challenging, and still is today from beginning to end. I think that’s the world of independent filmmaking, and there’s no way around it. How do you shoot this in the short amount of time, with very little resources and very little money?

I think that’s where the creativity comes in. We used nine minutes of real footage. That really helped give our film a bigger scope, because there are thousands of people in the frame and you don’t have to pay them as extras. There were many ways of making the film appear bigger on a smaller budget.

Having said that, it took me years to actually have it financed. The idea of a first- time director doing a political ensemble—when they do risk evaluations, which they do, that’s a risk. It was a difficult project to get financed. I tried on the first draft of my script and took it to some of the indie producers in Hollywood. They seemed interested, but none of them wanted to do it.

I then rewrote the script and took about a year and a half retuning it. I got it to a place that I thought was good, and then I also made a film. Basically, there are three documentaries made about the event, and I got those documentaries and cut them together. The fifteen minute film I made goes along with the chronology of the script. An ensemble script isn’t the easiest thing to read. I think giving it that visual really helped.

Cineaste: I know one of those documentaries is Jill Friedberg and Randy Rowland’s This Is What Democracy Looks Like. I saw some definite similarities between the documentary This is What Democracy Looks Like and your film.

Townsend: This Is What Democracy Looks Like was a big inspiration. I thought it was a really great documentary. I am hoping that this film will somehow encourage people to go back and look at it. One of the reasons for me making a feature was the fact that there were documentaries made, but nobody saw them except for maybe some activists. My idea is to mainstream it, to make a film that is still not exactly mainstream, but to make a film that hopefully has a chance with a mainstream audience, to shine attention onto the subject.

Cineaste: In the Thank You at the end of the film’s credits are listed activists who appeared in This Is What Democracy Looks Like, such as David Solnit and Rice Baker Yeboah. Did activists play much of a role in your research?

Townsend: Unfortunately, no. I just did it on my own, which is unfortunate. I would have loved to have known how to reach out more to people. Once we were a production, once we were on the move, a lot of activists came along and helped us out, which was great. Sometimes it was a little too late for some of it, which was unfortunate, but it was really great having actual activists participate in the film process.

Cineaste: How did they participate?

Townsend: Some of them were on set giving advice. “This looks right, this intersection takeover. Yeah, that’s how they would do it.” For example, in the intersection takeover Rice was there, and he helped a lot with the extras, making sure that they acted like activists and had that kind of energy and that drive. They really helped in making the background feel real, which was hugely important. Or we’d be at a spokescouncil meeting and they’d say, “Well, the spokes-council doesn’t really look like this.” Unfortunately, some of it, I just couldn’t change

Cineaste: What sort of things were you unable to change?

Townsend: For example, we were talking about a spokescouncil meeting, and David Solnit, ended up writing eighteen pages of script that he thought would be more of a realistic depiction of how a spokescouncil meeting happens. Unfortunately, it was eighteen pages of monologue, and I’m making a film, I’m not making a six-hour documentary. Creatively, I can’t do that. I understand that they want the film to delve deep into the direct-action tactics process, and I completely understand why an activist would want that, but unfortunately I was making a feature film, and I knew what I needed to do to make it.

The hardest thing in the whole process of making the film was what I had to leave out. I know more than anybody the pains of not being able to go in depth into every single issue the way I’d wanted, the way I did in my research. If you research and find out about these issues, they’re so frustrating, some of them make you so angry and upset at what is going on in this world—and you want to put that in a film.

But you can’t if you’re going to make a feature. If you’re making a documentary, perfect, go for it. That’s what a documentary is: a way to really explore the issues. But a feature is not. I had to make peace with that very early on. Always, first and foremost, in my mind, was that this film was a piece of entertainment.

Cineaste: What considerations were made in your casting? Among the main activists, there is obviously some racial diversity.

Townsend: The racial diversity thing, in one sense, was just an accident. While Andre Benjamin was always the first person I cast as Django, he’s actually the only actor who was the person I originally wanted for a role. In my research, in the documentaries, to me I saw a lot of variety of ethnicities in the documentary footage. But a lot of people then had this debate, “Where was the color in Seattle?” That was the title of an essay [by Elizabeth Martinez—ed .] in the book The Battle of Seattle. I thought I’d express that. So I put Andre’s character in as an African American, and he had a line that unfortunately got cut. He was wearing the turtle outfit and saying, “The police, if they see a black guy, they’re going to arrest him. They see a turtle, and they’re not going to do anything like that.” I think he liked that line.

Cineaste: Aside from the documentaries you watched, in interviews you have mentioned a number of films including Medium Cool, Battle of Algiers, and Network. What specifically did you draw from those films?

Townsend: Battle of Algiers is such a landmark film. In that film, you are there, the sort-of cinéma-vérité docudrama taken to the extreme. Obviously, that style has been emulated over and over again for the last three decades because of that film. Medium Cool was more visual. Haskell Wexler [the director and cinematographer of the film] is one of the greatest Directors of Photography of all. The out-of-focus stuff I just loved, the saturation of the colors, and the hand-held style. Network is just the greatest film of all time. Stylistically, I don’t think there is anything going on there, but the script is so far ahead of any script, ever. It’s just one of my favorite all-time films. Topically, I still think it’s probably more relevant then most films made today.

Cineaste: Network and Medium Cool to a large extent too, shares with Battle in Seattle this critique of the mass media. Medium Cool is also very different, very experimental. Did you experiment with different ways of telling your story before choosing the ensemble structure that you did? Or did you always have the ensemble in mind?

Townsend: When I first started, I didn’t have the ensemble in mind, but after a year and a half of research, that felt like the way to go. Then I thought, this is going to be interesting, purely in film terms stylistically, to have eleven or twelve characters. Editing it was fantastic and hugely challenging. But that was definitely always the style.

Cineaste: There is frequent misrepresentation that the police attacked the crowd after things got out of hand, after windows were broken. I was happy to see the film get this right—the police attack the crowd first. Was the chronology of the protest important to you?

Townsend: I’m glad you mention it because that’s the one issue I really wanted to set the record straight on. I probably researched this event more than anybody, and sometimes you would hear a fact being mentioned, and sometimes you would hear it mentioned again and again and again. I generally thought, the more it gets mentioned, probably the more truth to it. If you hear a fact once, and then it’s gone, maybe it happened, and maybe it didn’t.

Definitely, time and again, it was said that the police sprayed and pepper-gassed innocent, peaceful demonstrators. Time and again in the media, it was always referenced as the violent anarchists, and then the police responded, to which the mayor says, “The police responded appropriately.” I wanted to give that context, show that the mayor makes that decision, and the police do gas indiscriminately. And then, yes, anarchists come smashing around, and the police continue. That was a very, very important distinction. I think that was probably the one major issue that activists had problems with in regards to mainstream media.

Cineaste: Are you familiar with David Solnit’s project, “The Real Battle in Seattle”?

Townsend: Yes.

Cineaste: What are your thoughts on that?

Townsend: I think he feels like the event, the story, was not told by the activists in the first place, it was told by mainstream media, Time and Newsweek, and that it was in a sense distorted. I think he thought of our production as this big Hollywood film. It was difficult, because he came there not very open to what we were doing, in a sense, and then he set up this Web site called “The Real Battle in Seattle.” Good luck to him.

Luckily, our film was shown to a lot of activists, and overwhelmingly they appreciate what I’ve tried to do, and they understand that this is a rare opportunity where the debate actually gets focused on activists, in Hollywood. Although I don’t call my own film a Hollywood movie, because I don’t think it is—it’s absolutely independent and there’s a big distinction—what I am trying to do is make this a mainstream movie as much as possible. I think most activists realize that my intentions are good, and that this is a chance to reignite a debate, it’s a chance to refocus the spotlight. So it’s been really great. And then obviously there are just a few people who feel different, and that’s fine.

Cineaste: In your film you deal with issues that protesters were arguing over, not just between protesters and the WTO, but amongst protesters themselves. For instance, the issue of violence versus nonviolence. How did you decide to include those issues in the film?

Townsend: The anarchists are such a misunderstood and yet important aspect of the whole event. I didn’t want to make an anarchist movie, but I wanted to represent them. If you look at the Gap scene with Charlize, they’re looking at baby clothes and it’s all very sweet. And then, “Smash!” The window smashes. If there ever was an expression of why anarchists break windows, that’s the expression: to break the malaise. It’s to smash something and say, “Wake the fuck up.” In the cinema, it smashes everybody in the audience. People jump out of their seats in that moment. That’s I think, in one sense, what anarchists are trying to do as agitators.

I wanted that classic argument, nonviolence versus violence, and the anarchists saying, “We’re the ones who are going to make this day famous.” That’s kind of true, you know. One thing I liked about the research was that there were so many voices, and many of them were right and wrong at the same time. It was very hard to find a bad guy. I had big troubles with the film in the beginning because there was no antagonist, no singular bad guy, no villain.

Then that kind of became interesting to me, because, the Mayor, he’s not really the villain, he’s more of a tragic character. In my research, that’s what I looked at him as. He wasn’t perfect, but I don’t think he was a bad guy. The police, plenty of people will say “Fuck the police,” but I think most cops are just working-class joes doing a job. Some police are bad, but you can’t paint everyone with that brush.

The protesters were there for very noble reasons, but then their protest also disrupted some NGOs, like Doctors without Borders. That was a gray area. That doesn’t mean protesters are bad, but I just think its interesting how, in one sense, they disrupted each other. They’re both going there to fight the good fight and they end up disrupting each other—I like that, I like those gray areas. Some people don’t like that at all, but I thought that was one of the strengths of the film.

Then who are the bad guys? Well, they’re fucking faceless bureaucrats and faceless lobbyists, the worst kind of enemy of all.

Cineaste: Was it your intention to use the characters to delve deeper, to show gray areas? I’m thinking of Michelle Rodriguez’s character, Lou, she seems in between some issues in the film.

Townsend: Yeah, I think so, because I don’t think anything is black and white. There’s definitely the anarchist argument. I wanted to put that in there, because that was something I came up against time and time in the film. To have her appear early on as an anarchist was one part of it. More than anything, with Lou there’s a certain anger there that has nothing to do with activism, which I think is more of just a character thing.

That’s probably the hardest part for activists seeing the film, because they’re like, “Well, these characters are getting in the way of the facts.” It’s hard because they are meant to get in the way of the facts. This isn’t a documentary. Most people don’t know the world of activism. That’s kind of who I made the film for, is for the people who don’t know and get excited by it in the same way I got excited about it when I started researching it.

I didn’t want to do a docudrama where it’s just fly-on-the-wall constantly, and you never really get a sense of the characters. I wanted to make this a character-based film. The first half of the film is really more about the event, and setting up stuff, and the second half of the movie is a little slower, it’s a little bit more about the characters. Some people love it and go, “I really got attached to those characters.” Some people say, “There were so many characters, I found it hard to get attached to any single one.” That’s just what you get. You get people saying, “I really loved this one character, I really loved this other character.” I think that’s the nature of an ensemble film.

Cineaste: Since the protests there have been competing accounts of what happened—not only between the police and the city, and the protest organizers, but between the organizers themselves—nonprofits, direct-action organizers, anarchists. How did you parse through that? How did you decide which stories to focus on?

Townsend: I think time does it. I researched for a year and a half. In those eighteen months, I just let things digest. I was constantly reading all of these books. Some of them were obviously arguing against each other, but the more I researched, the better sense of it I got. In the end, I think the more work you do, the easier it is to synthesize the facts.

The ensemble nature came from the fact that there were so many sides to the event. I had to have protesters in there. I wanted to give the police a voice, because I felt like the real footage would villainize them enough. In my research, I read that some of the police were scared to go out there. They were not trained properly, they were not fed properly, they didn’t get to go to the can much. A lot of them didn’t get any sleep. That kind of stuff doesn’t justify their actions, but it certainly humanizes it, and I wanted to make sure that that was represented.

The hardest part of all my research was that there was very little information on what went on in the WTO, inside, because it’s nontransparent. My only way in was to the doctor with Doctors without Borders and the African delegate. They were the only instances I found of anything that happened internally.

The characters came from the search to represent the different sides and the different factions, and hopefully create some gray areas in there so that’s it not a black- and-white kind of movie. I definitely felt from all my research that most of the protesters were out there for the right reasons. My overall sense, just as a human being studying it all, I found that the people who advocated free trade, that kind of economic-shock therapy, I really found that hard to digest. I didn’t agree with them, and I ended up very much agreeing with the protesters asking for labor rights and good working standards, and good environmental standards, and safety standards.

I think those protesters were actually ahead of the curve. In 1999, the jury was still not in on the debate around free trade. Now, we’ve seen the financial crisis of East Asia, we’ve seen Argentina, we’ve seen time and again that free trade doesn’t work. I think time has caught up. Most people in 2008 are far more aware of the environment than they were in ’99. I think the film still has relevance.

Cineaste: Do you think the film has a role to play in the discussions and the movements since the protests?

Townsend: I hope so. I hope it does this year. If you look at the election, I think that Obama has politicized this whole new generation that needs to be politicized and needs to start caring about their country and where it’s going. Get involved; take action; participate. That’s what this film is about. It’s about a story that you probably don’t remember, and hopefully you get inspired when you see the film and ask, “Holy fuck! Why don’t I remember? I want to know more.”

It’s about participation. That’s a real democracy. Hopefully, the film shows the commitment that those protesters had and the level of patriotism. The power of the individual and the power of solidarity: all those issues are eternal. Ultimately, I just want the film to inspire people. You can be cynical about the film, but I’ve seen it inspire people already. That’s a huge thing to ask. If there’s one thing that I would like people to come away with, it is to be inspired.

- Immanuel Wallerstein, “Cancun: The Collapse of the Neoliberal Offensive.” Confronting Capitalism: Dispatches from a Global Movement. Edited by Eddie Yuen, Daniel Burton-Rose, and George Katsiaficas. New York: Soft Skull Press, 2004.

- Kristine Wong, “Shutting Us Out: Race, Class and the Framing of A Movement.” Confronting Capitalism: Dispatches from a Global Movement. Edited by Eddie Yuen, Daniel Burton-Rose, and George Katsiaficas. New York: Soft Skull Press, 2004.

Andrew Hedden lives in Seattle, WA and writes regularly for lucidscreening.com.

Copyright © 2008 by Cineaste Magazine

Cineaste, Vol. XXXIII, No. 4