The 2015 Oberhausen International Short Film Festival

By Jared Rapfogel

Takashi Ito's Spacy (1981)

Despite its strict focus on the art of the short film, the Internationale Kurzfilmtage Oberhausen (Oberhausen International Short Film Festival) is an event of many, somewhat disparate parts. Anchored by its Competition sections (International, German, North-Rhine Westphalian, and MuVi or music video), its greatest strengths normally lie elsewhere—in the numerous Profiles of individual artists, its short film Distributor showcases, and, more recently, in the Archive programs, which provide a platform to various film archives to present a selection of recently preserved films or gems from their collections. Each annual edition of the festival also features a “Theme” section, a carefully curated series of screenings of films new and old, from throughout the world, that are organized around a particular theme.

For those of us who focused our attention away from the Competition screenings, toward the (normally) more dependable ancillary sections, the 2015 edition of the festival was marred by an extremely disappointing Theme section, even as the especially strong Profile and Archives programs provided a large measure of redemption. To get the bad news out of the way immediately: the theme section was entitled “The Third Image—3D Cinema as Experiment,” and despite its promising premise, it was something of a disaster. Curated by filmmaker Björn Speidel and comprising six programs and an installation (by American artist Lucy Raven), it was a painfully perfect illustration of an approach to film programming in which concept trumps content. Speidel must have had a clear idea of what each program was supposed to accomplish and of the aspects of 3-D filmmaking that were to be represented, but in finding films to fit his construct, he seemed almost wholly indifferent to quality or (even more fatally) to the ways in which films enter into dialogue with or amplify each other.

Curating short film programs is not an easy task—it’s immensely challenging to select and position films so that a coherent and compelling overarching idea or theme emerges, even as the integrity and distinctive modus operandi of each individual work is allowed to shine through in its own right. The short film programmer faces pitfalls on either side. We’ve all seen programs consisting of fine films that nonetheless clash unproductively with each other. But more often the problem lies in the other direction, with curators who conjure up a pet concept and then proceed to find films onto which they can impose their idea—who, in other words, start with a concept and then shoehorn a group of films into this framework, rather than starting with the films themselves and perceiving within them a shared theme. In the context of programs like these, individual films are too often stripped of their many ideas, dimensions, and resonances, and reduced to an illustration of an idea to which they’re sometimes only tangentially related. Or, even worse from the standpoint of a viewer, such programs often include films that are present purely because they “fit” into the curator’s framework, though they’re of very little interest from any other perspective.

All of these pitfalls were on display in the 3-D program. Above all, the series encompassed too many films that were simply so awful that, giving the curator the benefit of the doubt, one could only assume they were present because they demonstrated some facet of 3-D filmmaking toward which he felt it was important to gesture. But a bad film is a bad film, and while it may make sense to allude to such works in an article or workshop about 3-D filmmaking, it makes none whatsoever to screen them in a film program—not only did their awfulness obscure any specific relevance they might have had, their inclusion did a disservice to the worthy films that they screened alongside. I’m thinking in particular of films like Celine Tricart’s Lapse of Time, a sub-Hugo work of sickening whimsy and preciousness and thuddingly obvious thematics, and Nakamura Ikuo’s Aurora Borealis 3D, a portrait of the Northern Lights that demonstrates that however magnificent the phenomenon may appear in person, photographed (in 2-D or 3-D) it comes across as clichéd postcard imagery, especially when accompanied by comically sentimental music. Programming these films represented, at best, a misapprehension that the purpose of a series exploring 3-D should be to focus on the raw technical possibilities of the medium, rather than on how talented creative artists have successfully utilized the format. To include failed experiments that are not entirely successful films but that represent honest, interesting attempts to apply 3-D in innovative ways is all well and good. But many of the films here were neither innovative with respect to 3-D nor valuable in any other context, and their inclusion in the series could only cheapen the other films with which they were shown.

The theme section was a terribly missed opportunity, since there’s no question that 3-D has become ubiquitous and has expanded from a primarily commercial strategy to a phenomenon whose potentialities avant-garde filmmakers and artists are increasingly experimenting with and exploring. This could have, and should have, been the whole story of the program, but at least there were a number of films that did illustrate the point. That the avant-garde embrace of 3-D is not a new development was demonstrated by the inclusion of Paul Sharits’s 3D-Movie (1975), a dynamic work of abstraction in which the screen is transformed into a pulsating, undulating field of dots whose rhythms and interactions, rendered in 3-D, become truly cosmic; and by two works from Ken Jacobs. Jacobs’s tireless, decades-long devotion to optical experiments of all kinds, and to stereoscopic filmmaking in particular, qualifies him as the godfather of experimental 3-D. He has been infatuated by the possibilities inherent in the technology for decades now, and has made dozens of films using various formats, including anaglyph, Pulfrich, and his own invention, Eternalism 3D (patent pending)—not to mention his Nervous Magic Lantern live performances, which induce a perceptual state very close to the three-dimensional.

Ken Jacobs's Capitalism: Child Labor (2006) uses a stereo photograph to create 3D effects

Jacobs—who has made a multitude of films that could’ve fit into the Oberhausen selection—was represented by Capitalism: Child Labor (2006) and Opening the 19th Century: 1896 (1990), both of which demonstrate his extraordinary ability to fuse the most challenging, visually stimulating perceptual experiments with an impassioned political and historical engagement. Both films utilize early photographic artifacts: for Capitalism: Child Labor (part of a series of Capitalism films), Jacobs digitally animates a stereographic photograph taken in a nineteenth-century thread factory, many of whose workers are children, while Opening the 19th Century: 1896 repurposes footage shot by the Lumière brothers in Cairo, Venice, and other cities (elsewhere in the theme program, Speidel included an early 3-D film by the Lumière brothers themselves, a 1935 “remake” of their 1895 short, L’Arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat). In the first film, Jacobs demonstrates an effect he’s returned to many times: by rapidly alternating the two sides of the original stereographic image, Jacobs simultaneously reveals the sense of depth the photograph was designed to express and brings the image (and the individuals documented therein) to life by unleashing a jittery (Jacobs favors the term “nervous”) but charged sense of back-and-forth movement. The effect is sublime, in part because there’s a further dimension to it that’s difficult to account for—by alternating between these two frames, the image appears to be perpetually revolving, though without actually changing its orientation. There’s something frustrating about this motion without progress, but at the same time it results in a moving-image that’s far more alive than you’d expect a simple alternation between frames to generate. This is the film’s foundation, but as it progresses, Jacobs uses his digital arsenal to zoom in on certain parts of the composition, usually in order to focus on a particular individual’s expression or gesture, a strategy that seems almost to restore these long-dead factory workers to life.

Opening the 19th Century: 1896 is similarly intoxicated by the reanimating capacity of photography, but here Jacobs’s intervention is not to bestow motion upon a still image, but to reveal depth within a two-dimensional moving image, a feat he achieves by means of the Pulfrich effect, in which lateral motion is transformed into 3-D by placing a dark filter over one eye. By slowing down the light that reaches that eye, the two-dimensional image effectively becomes a stereoscopic one, creating as convincing a three-dimensional effect as any other format. With this simple intervention, Jacobs creates a film about photography, the urge towards documentation, changing technologies (photography to cinema, 2-D to 3-D), and the unstable relationship between reality and representation.

In terms of more contemporary works, two of the standouts were Tim Geraghty’s Something Might Happen and Blake Williams’s Red Capriccio. In the interests of full disclosure, Geraghty is a close colleague and friend—but his recent 3-D work is so breathtakingly multilayered and so committed to exploring untapped dimensions of stereoscopic filmmaking that I can’t resist the temptation to discuss it. Geraghty is one of the few filmmakers I know of (and certainly one of the few included in the theme section) who exploit 3-D for its capacity to play with multiple planes of imagery. 3-D is so often spoken of as a technology that allows filmmakers to work in depth, but few acknowledge the fact that stereoscopic 3-D does not capture anything like true, fully articulated depth, but rather transforms reality into a series of planes, resulting in something no less artificial and stylized than conventional 2-D photography. There is a sculptural effect to be sure, but there is also a planar effect—and Geraghty is one of the few filmmakers who fully exploits both of these qualities of 3-D, and who probes the intersection between them.

Tim Geraghty's Something Might Happen (2014) features multiple layers of 3D imagery

Something Might Happen is a landscape study, a portrait of a piece of land in rural Virginia during the emergence of a deafeningly loud species of cicada that appears once every seventeen years. But while Geraghty does use stereoscopic photography to portray the landscape in depth, just as often he uses the format to depict multiple, distinct layers of imagery. In other words, he uses 3-D not so much to create a naturalistic illusion of depth, but to layer imagery in a way that’s not possible in 2-D. In effect, he’s taking the technique of multiple-exposure or optical juxtaposition that filmmakers such as Bruce Baillie and Gregory Markopoulos have used to create masterpieces like Castro Street (1966) or Sorrows (1969), and projecting it into a third dimension, so that the multiple layers interact in radically new and dizzying ways—often, in fact, in ways that are difficult to perceptually and mentally process. Like those earlier works, Something Might Happen is a film of extraordinary density—Geraghty deploys the red/cyan anaglyph filtering at times to create the familiar sense of depth, but at others to send unrelated images to each eye, while often juxtaposing images from both categories over each other, and pairing the whole visual edifice with a similarly overwhelming, cacophonous soundtrack. Something Might Happen’s mind-expanding quality—headache-inducing yet exhilarating—signals a genuinely innovative exploration of 3-D, one that is largely missing from most of the contemporary work Speidel unearthed for the program.

Though distinctly different from Geraghty’s film in structure, tone, and technique, Blake Williams’s Red Capriccio embodies a similarly liberated approach to anaglyph 3-D—in true avant-garde form (since after all, the avant-garde tradition has always been dedicated to exploring the vast realms of cinematic possibility generally ignored by commercial filmmaking), Geraghty and Williams display not only an interest in the tried-and-true use of the technology but also, more importantly, an inspired curiosity about what else it can do.

Red Capriccio calls attention to 3-D’s paradoxical nature: ostensibly more “realistic,” 3-D in fact results in such an artificial, stylized form of dimensionality that it creates a sense of unreality. It envelops us in a world, but one that is profoundly defamiliarized. Williams takes advantage of this defamiliarizing quality to create a witty, haiku-like, yet haunting mood piece constructed entirely from (2-D) YouTube footage. The world of Red Capriccio appears to be populated not by people but solely by flashing lights and police cars, both of which exhibit strange behaviors that suggest nonverbal attempts to communicate.

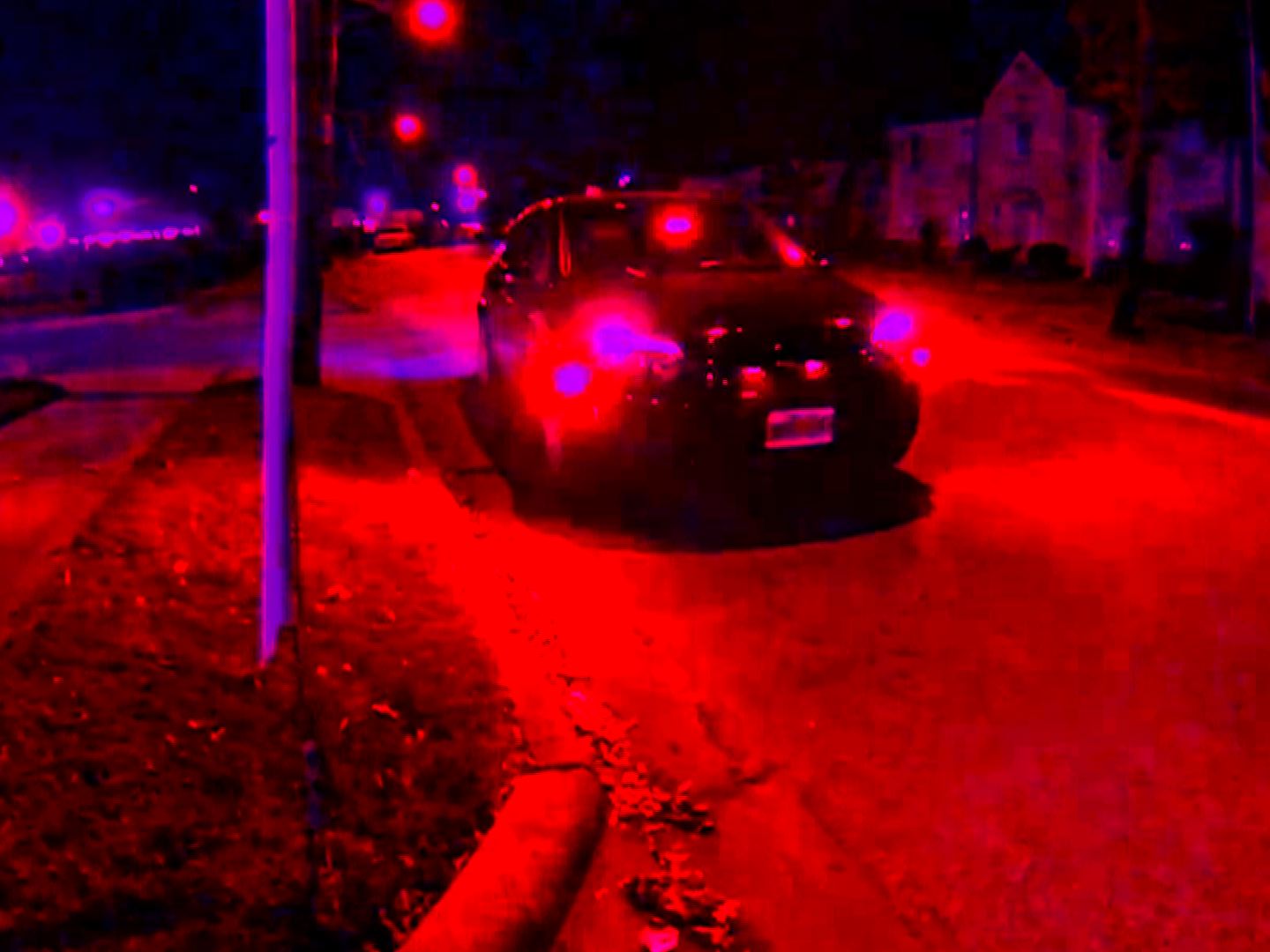

Blake Williams's Red Capriccio (2014) is constructed using found footage sourced from YouTube

The film opens with footage in which an unmarked and seemingly abandoned police car is slowly approached and circled. With the police car’s multiple flashing lights at full blast, the image is from the start quasiabstract, the flashing lights turning the screen into a canvas of vibrating color fields. Williams amplifies this by repeating the footage several times, varying the balance between red and cyan each time (and accompanying it with a dramatic musical cue), and finally ending the sequence by deconstructing it into a rapidly edited, condensed version, whose flashing frames mirror the car’s flashing lights. Next comes a series of through-the-windshield shots of highways at night, with lightning flashing on the horizon, before Williams cuts to a suburban house that’s raked by two powerful spotlights, one rendered in red, the other in cyan. After a very brief glimpse of children in the back of a car (the only explicitly human presence in the film), the film transitions to the (again depopulated) interior of a club, whose bright spotlights flash and sweep the room in what, again, seems like some kind of secret code, before a final shot of a police car wildly donuting, as if dancing to the music from the club. One of the most uncanny, intuitive, and oddly funny found-footage films in recent memory, Red Capriccio is an intentionally unassuming film (it lasts all of seven minutes) but it truly casts a spell. And while this spell owes a great deal to its use of anaglyph “3-D,” Williams seems at least as attracted to the ability to play with competing red and cyan filters, to a kind of painterly use of anaglyph, as to a quality of depth. Or rather, for both Geraghty and Williams, 3-D offers far more than access to naturalistic depth—it offers an imagistic depth, a third dimension in which to extend their visual explorations.

Just as structuralist filmmakers in the past took pains to emphasize the phenomenon by which still images projected in rapid succession take on the appearance of fluid movement, filmmakers like Geraghty and Williams subtly emphasize the phenomenon by which, in 3-D, two images are integrated in our minds (with an assist from a pair of glasses) into a single, three-dimensional image. In their work, and in that of other avant-garde filmmakers experimenting with 3-D, the multiplicity of images lurking beneath the apparently single 3-D image is brought to the surface—in Geraghty’s case by layering multiple images on top of each other, with the images both fusing and not quite fusing into one; in Williams’s case by creating a similar, not-quite-melding between the red and cyan components. If 3-D in experimental films often seems not quite to “work,” it’s precisely this disjunction or slippage that the filmmakers celebrate and engage with.

But enough about the 3-D section, whose shortcomings were, thankfully, largely offset by a particularly strong series of Profiles, and by the always-dependable Archives programs. I’ve written at length about the Archives programs in the past, so suffice it to say that this component of the festival, which was inaugurated in 2013, remains an invaluable part of Oberhausen. Each year several archives are invited to present a program highlighting recently preserved films as well as rarely screened items from their vaults. But these screenings amount to more than a rich opportunity to see rare films in ideal conditions—each program is presented by one of the institution’s archivists, who provide a glimpse into the world of film archiving and preservation, revealing the mechanics, technological challenges, and selection criteria that underlie the effort to preserve cinematic works, as well as detailing their extensive research into the films they’ve worked on. The Archive screenings are invariably fascinating and stimulating film programs, as well as master classes on the art of film preservation. This year’s featured archives were the British Film Institute (represented by Will Fowler, who unveiled the Super 8mm films of John Maybury), the Academy Film Archive (Mark Toscano curated a selection of lesser known American avant-garde films from the 1960s–1990s), the Austrian Film Museum (Alejandro Bachmann hosted a highly eclectic program bringing together amateur films, advertisements, experimental works, and screen tests), and the National Film Center, Tokyo (Tochigi Akira presented a selection of amateur films, primarily from the 1930s).

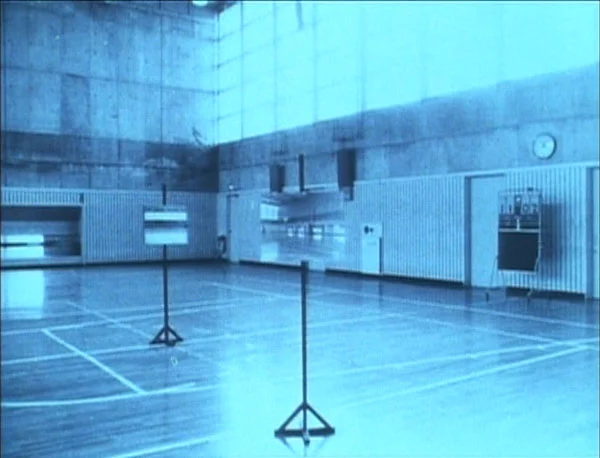

In Takashi Ito's Spacy (1981), the camera is continually swallowed up by two-dimensional images mounted on easels

The Profiled filmmakers this year were Ito Takashi, Oberhausen veteran Jennifer Reeder, William Raban, Vipin Vijay, and Erkka Nissinen. To my regret, I was unable to see the programs of work by Vijay and Nissinen, but the first three provided some of the most memorable moments of the 2015 festival. I was not previously familiar with Ito Takashi, and if his later work delivered diminishing returns (becoming increasingly slick and flashy), early films such as Noh (1977), Movement 2 (1979), Movement 3 (1980), and especially Spacy (1981) were revelatory. All of these films utilize and explore the single frame, creating dynamic and provocative investigations into the relationship between still imagery and motion (which of course lies at the heart of cinema). Spacy is clearly Ito’s masterpiece, a dizzying experiment whose propulsive electronic soundtrack and space-bending maneuvers add up to a uniquely intense and otherworldly experience. As simple in concept as it is vertiginous in effect, Spacy takes place in an indoor basketball court, throughout which Ito has placed easels displaying photographs of the court itself. Filming one frame at a time, Ito moves the camera forwards towards these easels until the photographs fill the frame. Since the photographs represent wide angle views of the court, every time the camera completes its “zoom-in” and the photograph fills the frame, the camera has essentially started over from where it began, seemingly swallowed up into the still image which then becomes the “reality” of the film. Perpetually in motion (or more accurately, an apparent motion created by the rapidly changing stills—but then, this is true of every movie), Spacy becomes a continuous loop, whose dynamism grows increasingly overwhelming as Ito carries out every possible permutation of his scenario, multiplying the number of easels, pivoting the camera as it hurtles towards each image, reversing the motion of the camera, and even placing some of the images on the floor of the court. The result is a profoundly disorienting and space-defying film that systematically calls into question the nature (still and in motion, two-dimensional and three-dimensional) of every image.

Jennifer Reeder operates in an entirely different mode—or rather, many different modes. Born in Ohio and based in Chicago, Reeder burst on the scene in 1995 with White Trash Girl—The Devil Inside, a gleefully trashy, hilariously aggressive, feminist punk provocation that packs a whole career’s worth of inventiveness, vitality, and sociopolitical ire into its blink-and-you-miss-it eight minutes. In the years since, Reeder’s body of work has expanded to include a handful of feature films, nonnarrative experimental shorts (often structured around popular music), and, more recently, a series of mid-length narrative films that invariably concern the lives of teenage and/or middle-aged women. The Oberhausen selection, which was curated by Jennifer Lange (curator at the Wexner Center for the Arts in Columbus, Ohio, Reeder’s hometown), featured a generous selection of these mid-length films—And I Will Rise if Only to Hold You Down (2011), Tears Cannot Restore Her: Therefore, I Weep (2011), A Million Miles Away (2014), and Blood Below the Skin (2015)—which find Reeder developing a genre that’s distinctly her own, at least within the context of the experimental film world. In style, tone, and approach to storytelling, these films have little in common with White Trash Girl—The Devil Inside, or with Reeder’s nonnarrative/installation work—gentle, sensitive, and large-hearted where White Trash Girl is loud, brash, and (at least ostensibly) nihilistic. But Reeder’s preoccupation with female psychology and experience—with a twin focus on teenage girls and struggling, single, middle-aged women—and her spirit of empowerment, are clear and present. And within the world of noncommercial, so-called experimental filmmaking, Reeder’s unapologetic adoption of relatively conventional stylistic and narrative methods is almost radical, a reflection of the sense of inclusiveness and lack of vanity that suffuses her treatment of her characters, actors, and themes. Reeder has increasingly chosen to practice a form of filmmaking whose “independence” is signaled not by its rarefied aesthetics but by its dedication to depicting realms of (female) experience that are neglected in commercial and independent cinema alike, and by her collaborative method of working with her casts and crews.

Kesley Ashby-Middleton in Jennifer Reeder's Blood Below the Skin (2015)

Her most recent film, Blood Below the Skin, is perhaps the most accomplished of these narrative works: her handling of her (largely nonprofessional) actresses, her unshowy but emotionally expressive imagery, and the precision of her storytelling are all rendered with a newfound level of confidence. Like And I Will Rise if Only to Hold You Down and A Million Miles Away, the new film splits its focus between a handful of teenage girls who struggle to form identities, establish connections, and manage their fraught home lives, and a middle-aged woman whose sense of self and emotional stability is perhaps even more fragile (Million and Blood also feature almost identical casts). It’s a remarkably graceful film whose storytelling is as concentrated as its sensibility and themes are expansive.

Not entirely unlike Reeder’s, William Raban’s work has shifted over the years, becoming in some ways less formally challenging while growing both more accessible and more explicitly engaged in political and social concerns. Raban’s early films—View (1970), River Yar (1972), Broadwalk (1972), Diagonal (1973), Take Measure (1973), 2’45 (1973-2014), and others—fit squarely in the tradition of structuralist and expanded cinema, utilizing time lapse, multiple projectors, and, in some cases, audience interaction (last year’s theme program—“Film Without Film”—featured both Take Measure and 2’45; in the former, a length of film, depicting a motion-picture-frame counter, is stretched from the screen to the projection booth, retracting backwards over the heads of the audience as it passes through the projector, while in the perpetually growing 2’45, each time the film is screened the audience’s reaction is incorporated into the subsequent screening). These frankly experimental works, as well as Raban’s role in managing the London Film-Makers’ Coop, established him as a key member of the UK avant-garde film scene. With the exception of View, however, none of these early works were included in his three-program survey at Oberhausen. The survey’s curator, Jonathan P. Watts, chose instead to focus on the films Raban has made since 1992. This was mildly disappointing for those of us who are strongly drawn to 1970s avant-garde cinema, and who have only a partial familiarity with Raban’s early work. But it was an interesting choice, especially since Raban’s trajectory has been quite unusual (albeit mirrored by Reeder’s career) in moving from unmistakably avant-garde techniques to a distinctly different and arguably more widely accessible mode.

Raban’s later works demonstrate an explicit concern with English society, politics, and urban development that stand in striking contrast to the political disengagement of so much of structuralist cinema. Raban’s films of the 1990s and 2000s (at least the ones that were screened at Oberhausen) are consistently preoccupied by the transformations that have befallen English society over the past quarter century, and on the way they’ve manifested themselves in London’s skyline. Sundial (1992) and A13 (1994) take aim at the Canary Wharf Tower, while MM (2002) is similarly focused on the Millennium Dome, two super structures that Raban seizes upon as all-too-conspicuous symbols of the yawning class and economic disparities that were fueled by Margaret Thatcher and her ilk, and that have been nursed by the neoliberal governments that followed. These films, and the other equally socially and politically attuned films that screened alongside them, speak a language entirely different from that of conventional documentaries, and display a compositional and conceptual rigor that sets them apart too from the overly-familiar city-symphony films they in some ways resemble. But in contrast to structuralist cinema, with its emphasis on the materiality of film, on stripping the medium to its bare elements, his later films find him directing his attention squarely towards the world at large, towards the structures of urban and social organization.

The artist Stephen Cripps in William Raban's 72-82 (2014)

If Raban’s early films were for the most part missing from the Oberhausen survey, they were present in a sense in the first program, which was devoted to his most recent, feature-length work, 72–82 (2014). Functioning as a kind of bridge between the different chapters of Raban’s career (it even encompasses excerpts from some of Raban’s early films), this film chronicles the first decade of the groundbreaking London arts organization Acme, which played a crucial role in London’s art world in the 1970s, both thanks to the seminal Acme Gallery and to its creation of a program by which abandoned and sometimes doomed buildings were made available to artists as studios. Though 72–82 appears to follow the template of so many historical documentaries, relying on archival footage and talking heads, it’s both a stellar example of the form and in a key sense far more thoughtfully and rigorously constructed than most. Thanks to an image track composed entirely of archival material (moving image footage as well as photographs, audio recordings, exhibition posters, brochures, and more), with not a shred of banal, contemporary connective tissue, 72–82 is more of an historical collage than a Ken Burns-like illustrated lecture. And, as signaled by the film’s subtitle, “Fallibility of Memory?,” Raban subtly reconfigures the documentary format to emphasize the process by which history is not revealed but rather constructed, even by direct participants (of whom Raban himself is one—he exhibited his work in several shows at the Acme Gallery and lives, to this day, in an Acme-owned house).

Most importantly, 72–82 trains a spotlight on a fascinating organization, and an extraordinary period in London’s cultural life, awash with young artists creating what seems to be truly singular, vanguard work in every kind of media imaginable. And any fatigue at archival-footage-filled documentaries is quickly eradicated thanks to the sheer wondrousness of the documentation Raban has unearthed. Generous time is devoted to footage of various performances and happenings—mostly by artists totally unknown to me, yet by all appearances very much worthy of further research. Most memorable of all (truly worth the price of admission) is the chapter devoted to Stephen Cripps, an artist who was apparently inordinately fond of explosive pyrotechnics (and who died in 1982 at the tender age of twenty-nine). 72–82 contains documentation of one of his Acme Gallery performances that’s shocking, scary, and hilarious in equal measure, and suggests that Cripps may be (or may have been, had he lived into his thirties) a figure to add to the pantheon of profoundly subversive, wildly misbehaved, and perhaps genuinely unhinged twentieth-century artists, alongside Jack Smith, Harry Smith, Kenneth Anger, Chris Burden, Joe Coleman, and others. At a festival in which some of the expected fireworks fizzled out, Cripps’s very literal fireworks provided a welcome blast of energy and inspiration, cutting through the curatorial missteps, and demonstrating that, even in an off year, Oberhausen always provides its share of revelatory discoveries.

Jared Rapfogel is a member of the Cineaste editorial board and film programmer at Anthology Film Archives in New York City.

For more information on the Oberhausen Short Film Festival, click here.

Copyright © 2015 by Cineaste Magazine

Cineaste, Vol. XL, No. 4