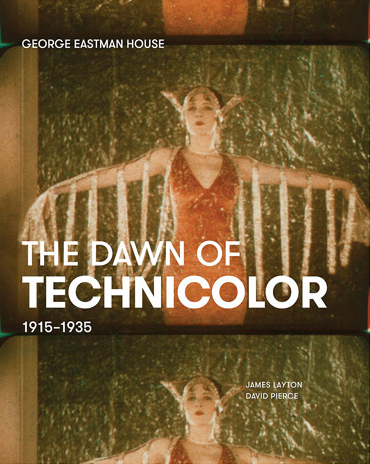

The Dawn of Technicolor, 1915–1935

by James Layton and David Pierce. Rochester, NY: George Eastman House, 2015. 440 pp., illus. Hardcover: $76.00.

Reviewed by Robert Cashill

Technicolor is the new black at repertory houses this year. Among several programs celebrating the centenary of the process was one at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, “Glorious Technicolor: From George Eastman House and Beyond,” a comprehensive survey encompassing sixty feature films, including classic achievements in cinematography including The Wizard of Oz (1939), Blood and Sand (1941), and Duel in the Sun (1947). You won’t find much mention of those in this book, which stops short of the ultimate realization of Technicolor on celluloid in those dreamy, dazzling fantasias. This is the nuts-and-bolts story of twenty years’ worth of often frustrating experimentation and the eternal struggle between art and commerce, and it’s a page turner—with many pages to turn.

The problem with just jumping into a tome like this (time to reinforce your coffee table, or buy a new one) is that the many gorgeous illustrations will catch your eye and pull focus from the illuminating text. It’s best to dwell on them for a few minutes. (And, no, your eyes aren’t deceiving you: the book’s pages are edged in red and green, for a “two-strip” effect, appropriate for the story of how two-strip Technicolor came to be.) That’s Katharine Hepburn in a breathtaking test shot for a film about Joan of Arc that was realized without her. A color production sketch for the 1934 short La Cucaracha is shown opposite a still from the film, and the match is close. Reproductions of frames of nitrate film are sprinkled throughout. The book’s final section, an annotated filmography of two-color titles produced between 1917 and 1937, is studded with lovely photos, and interesting notes about each production. You can loiter for quite some time there, and bemoan the “survival status” of too many of these historic efforts, some only available in single frames.

Given that this volume hails from the George Eastman House of Photography, it’s no surprise that it’s a gearhead’s delight, with plenty of technical facts and figures, and sidebars about the key technologists who participated in the birth of the process. But Layton and Pierce, both film historians, don’t stint on the human drama, and the interaction of strong personalities. Technicolor was, for engineer Burton T. Westcott and Massachusetts Institute of Technology grads Daniel Comstock and Herbert T. Kalmus, strictly business, something they could improve upon (the first color processes were terribly unstable, and gave viewers headaches) and sell to studios that might be looking to differentiate their offerings from black and white, which already consumed a great deal of light. Nothing came easy, as much faster film stocks needed to be devised and other technical hurdles needed to be overcome. Kalmus and his wife, Natalie (the company’s “Technicolor Color Director,” whose presence on sets often irritated filmmakers), carried on long after the other partners had left.

Anna May Wong in the two-strip Technicolor feature The Toll of the Sea (1922)

Early on, two-strip Technicolor (one film was dyed red in the lab and the other was dyed blue-green) was a flop; the images had an embalmed look and two projectors had to run simultaneously for them to be viewed, a difficult feat for projectionists. The two strips were then glued together, which was a little more palatable, and resulted in one of the more impressive titles, 1922’s The Toll of the Sea, a Madame Butterfly adaptation starring Anna May Wong. But it was limited, even after advances made gluing obsolete, and color was prohibitively expensive. Filmmakers like Douglas Fairbanks pushed the processing to its limits on movies like The Black Pirate (1926), but balked at further productions, making company finances precarious. Elaborate flops like MGM’s The Mysterious Island (1929), a hodgepodge four years in the making, were also damaging. Actors complained. Lionel Atwill, the star of the two-strip thrillers Doctor X (1932) and Mystery of the Wax Museum (1933), said the lights “bake your brains and eat up the red corpuscles in the blood.”

The book should end on a high note, with the landmark feature-film debut of three-strip, full-spectrum Technicolor on Becky Sharp (1935). But the authors conclude that “the initial beliefs that the appeal of color was self-evident and that the addition of color to films would justify itself in terms of increased attendance never proved true.” We’ll have to wait for the sequel to see a reversal of fortunes. Until then, revel in this richly hued history, which has been restored to vivid life.

Robert Cashill, a member of the Online Film Critics Society, is a Cineaste editor and the Film Editor of Popdose.com.

To purchase The Dawn of Technicolor, click here.

Copyright © 2015 by Cineaste Magazine

Cineaste, Vol. XL, No. 4