The Other 1968s (Web Exclusive)

by Clarence Tsui

Walking down a side street in the very central second arrondissement of Paris one morning in March, I chanced upon an announcement in the window display in a small bookstore advertising an upcoming talk about the possibility to “write a world history of 1968.” Amidst the “May ’68” fever gripping the French capital—ranging from the protest-chic window displays at upmarket fashion houses, to the commemorative magazines on sale at press kiosks—this small and intimate happening was proof of the efforts to expand the understanding of that historical landmark as part of an interconnected, global phenomenon.

And for one week in the French capital this spring, I witnessed how films and videos were deployed to evoke and amplify the internationalist aspects of 1968, in a timely riposte to the xenophobia advocated by right-leaning political strongmen around the world. From the Cinéma du Réel documentary festival at the Centre Pompidou to a multimedia exhibition at Nanterre, programmers and curators tried to reshape the simplistic representation of May 1968 as merely a display of bourgeois belligerence from beautiful, beret-wearing bohemians, as Bernando Bertolucci’s The Dreamers (2003) and Michel Hazanavicius’s Redoubtable (aka Godard Mon Amour, 2017) would like us to believe.

Trading in Gallic stereotypes, these two films—and certainly many others before them—were the result of what British historian Daniel A. Gordon, in his 2008 essay, “Memories of 1968 in France: Reflections of the 40th Anniversary,” described as a “triple reduction” of that fateful year. The dominant cultural view, he wrote then, was to limit les événements to the sole month of May, its geographical terrain to Paris or even to the Latin Quarter, and its protagonists only to young university students with their utopian ideals and catchy slogans.

But 1968 was, of course, more than just a mythical, month-long manifestation of eroticism, ennui, and existential crises by the Seine. Rather, the revolt was very much nurtured by the multiple influences and ideologies arriving on French shores during the early to mid-1960s. Consider the origins of some of the texts circulating widely among students who took over the Sorbonne in May 1968: On the Poverty of Student Life, a provocative polemic that chastises apolitical students for being “stoic slaves” and progressives as peddling “political false consciousness at its virgin state,” was written in 1966 by the Tunisian-born Situationist Mustapha Khayati. An Open Letter to the Party, a pointed analysis about the world being split between Western imperialism and the Soviet Union’s fossilized bureaucratic version of communism, was the work of Polish dissidents Jacek Kuroń and Karol Modzelewski.

To (mis)quote the title of Jean-Luc Godard’s 1976 film, Ici et ailleurs, about the slippery nature of media representations of reality, 1968 was as much about “elsewhere” as it was about “here” in Paris, if not more. Activists, artists, and filmmakers had demanded the overthrow of the established social order in Japan, West Germany, and Mexico well before their French counterparts did—and it’s perhaps about time that this was acknowledged on screens large and small across Paris.

In Nanterre, the suburb on the western fringes of Paris, where a takeover of a university administration building in March 1968 kick-started the student activism across the city in the months to follow, the municipal arts space La Terrasse hosted “1968/2018, des métamorphoses à l’oeuvre” (“the metamorphosis of an art work”), a multimedia exhibition offering a “heterodoxy of perspectives” on les événements from across class, gender, and national divides.

Cinétracts (1968)

Admittedly, La Chinoise (1967) and the Chris Marker-initiated Cinétracts (1968), a set of thirty-six unsigned agit-prop shorts about what happened that May, took pride of place in the show, with both films playing in a loop on TV screens. Categorized as “historical oeuvres”, however, they seemed to serve more as points of reference or departure for pieces marked as “contemporary oeuvres.”

In an attempt to update and expand the scope of the 1968 Cinétracts, Frank Smith appropriated viral videos online to depict a “violent and chaotic” twenty-first century as grim as that of his predecessors. Les films du monde comprises nineteen shorts, which, among other things, broached police brutality in the United States, the war in Syria, political protests in Hong Kong, and the dangerous crossings of refugees across the Mediterranean Sea. Adding his own voice-overs and on-screen texts, Smith questions both the social order and our understanding of it through what he describes as a “shifting, multiple and multipolar” representation of the world.

In their introduction to 1968: The World Transformed (2008), Carole Fink, Philipp Gassert, and Detlef Junker wrote of how left-leaning soixante-huitards removed Stakhanovite workers from their pedestals and replaced them with “heroic Third World fighters.” Rather than simply taking the cue from their own history—the French Revolution, say, or the Paris Commune—the young French rebels sought inspiration from the doctrines of Mao Zedong, Che Guevara, or Ho Chi Minh, or the feats attained by their fellow student activists in the Americas, Asia, and Africa.

This celebration of these international struggles was evident at the Cinéma du Réel this year. The festival was perhaps as its most militant in its section dedicated to Shinsuke Ogawa, the Japanese documentarian who spent nearly his entire life chronicling radical resistance movements from up close. Having cut his teeth making publicity and educational films for a publishing house, the then young filmmaker found his metier by establishing his own independent outfit, Ogawa Pro, and started making documentaries about Japan’s burgeoning social movements “from the inside”: his modus operandi was to immerse himself in the lives of the activists and produce a detailed and intimate chronicle of their work.

Shinsuke Ogawa

While Godard was still contemplating the merits of converting to Maoism and Chris Marker was still more than a year away from linking up with striking factory workers to form the filmmaking collective Medvedkin Group, Ogawa had already revolutionized Japanese independent cinema by joining hands with student radicals and protesting peasants in the making of highly politicized work. Spearheading the Réel’s Ogawa showcase was Sea of Youth: Four Correspondence Course Students (1966) and Forests of Oppression: A Record of the Struggle at Takasaki City University of Economics (1967), in which the filmmaker recorded the fight of activists who barricaded themselves inside universities with the hope of planning a campus and country-wide insurrection. While obviously sympathetic to their cause, Ogawa also highlighted their questionably harsh routines: their belligerence against students who did not share their views, their anxiety about attacks from the authorities and right-wing thugs, and their desperation as they sense the disintegration of their own movement.

The Battle Front for the Liberation in Japan: Summer in Sanrizuka (1968)

Five decades later, the films remain scintillating documents of those fiery times. Forests of Oppression ends with a student leader saying his failure could pave way for future struggles, and “we’ll fight on until the end.” It’s a struggle Ogawa embraced heartily, his defiance against what was perceived as the pro-Establishment agenda of mainstream news channels illustrated further through Report from Haneda (1967) and The Battle Front for the Liberation in Japan: Summer in Sanrizuka (1968). These two films, also shown at the Réel, revolve around the rural resistance against the Japanese government’s attempts to raze villages and build a new airport outside Tokyo. Having settled themselves into the village and lived with the local farmers, Ogawa and his team would make a further seven films about this struggle in the next decade, long after revolutionary moments in France (or elsewhere) had faded from the view.

Forests of Oppression: A Record of the Struggle at Takasaki City University of Economics (1967)

With a program titled “For Another ’68,” the Réel also sought to reshape long-running perceptions of 1968 and also what “classical activist cinema” should be like. Mirroring the festival’s general intentions to commemorate its fortieth edition by exploring the nature of reality and the also the documentary genre, programmer Federico Rossin probed the social uprisings fifty years ago by exploring what he described as the corresponding “revolution of artistic forms” from filmmakers from around the world.

In the section dedicated to Vietnam—or just “Nam,” to give the sub-program its official title—there’s no place for obvious candidates like the French omnibus Far from Vietnam (1967), Emile de Antonio’s The Year of the Pig (1969), or Peter Davis’s Hearts and Minds (1974). Veering away from the canon, Rossin picked titles taking potshots at the United States’ protracted and brutal military intervention in Southeast Asia through more experimental means. Some, for example, choose to lambast Euro-American complacency of the atrocities unfolding in Vietnam by juxtaposing images of violence from “over there” (that is, “elsewhere”) with pop culture (“here”).

Viet Flakes (1965)

Combining a ceaseless stream of photos of traumatized Vietnamese civilians with a soundtrack comprising Bach, Buddhist chants, and the Beatles, Carolee Schneeman’s Viet Flakes (1965) unfolds like a delirious dream that very much reflects how the West, apparently at once priding itself as the custodian of civilization (embodied in classical music) and indulging in material pleasures (symbolized by pop music), regard images of (other people’s) pains as mere flickers in the consciousness. In Harun Farocki’s White Christmas (1968), Bing Crosby’s crooning underscores sequences of German children meeting Santa Claus and playing with their new toys while comfortably ensconced in a country house. But this facade of bourgeois comfort has to give: a boy’s model house explodes, amidst texts decrying the suffering of Vietnamese children under U.S. bombing raids and photographs depicting these young victims.

White Christmas (1968)

Some, meanwhile, deployed even more abstract metaphors. Now largely known for his minimalist sculptures and land art, Walter De Maria was present here with his 1969 short film Hard Core, in which a gunslinger’s shoot-out punctuate a series of slow and protracted shots of a barren, windswept desert. The film then ends with a static shot of an Asian girl. Alluding to the iconography of Westerns, the film could be interpreted as cowboys trying to conquer a new Wild West and realize their Manifest Destiny on other shores: a nod, perhaps, to Washington’s ever-expanding campaigns in Vietnam and beyond.

On the other end of the spectrum, Carlos Bustamante and João Silverio Trevisan illustrated the urgency of their cause with films heavily reliant on rapid editing of a wealth of source material. Titled after the Latin motto of the Green Berets, Bustamante’s 1968 piece De Oppresso Liber (“To liberate the oppressed”) shows the United States doing exactly the opposite of that, as shown by the machine-gun montages of the devastation the country’s soldiers unleashed on Vietnam’s citizens. Trevisan’s Rebellion (1969), meanwhile, contains rarely seen images of South Vietnamese students protesting against the American-led war on their home turf, amidst footage of similar acts of resistance (and subsequent repression) around the world. It ends with an on-screen text—shown in seven languages—which says: “We must dare to think, to speak, to act, to be bold and not to be intimidated by the great names in authority.”

De Oppresso Liber (1968)

Break the Power of Manipulators (1968)

For activist/artists in 1968, the mainstream media were part of that authority. As part of a section titled Guerilla Media, Heike Sander’s Break the Power of Manipulators (1968) combined documentary footage and expositional sequences to reveal the way German news baron Axel Springer propped up the establishment and fanned antileft sentiments through the wide gamut of broadsheets, tabloids, and magazines he owned. Co-written by Farocki, the film ends with a call for people to unshackle themselves from Springer’s media machine. Helena Lumbreras and Mariano Lisa did something similar in Fourth Estate (1970), in which they also offered a map of the “imperialist” control of the Spanish press by dictator Francisco Franco and his allies, and how they played up the “lawlessness” in France and the United States in 1968 to whip up fears against calls for democracy. Concluding this analysis, the film asks people to make their own press with typewriters, copy papers, and basic ink printing presses.

Fourth Estate (1970)

Underpinning these pamphlet films is a wish for people to imagine new possibilities and break free from constraints. That might very well include an attempt to defy expectations shaped by long-held notions of the self and the other. None of the films grouped under Palestine, for example, are the typical militant treatises produced by the Palestine Film Unit or the filmmaking arms of the various factions within the Palestinian Liberation Organization.

Produced in Syria, Iraqi director Kais al-Zubaidi’s The Visit (1970) is a melancholic piece switching between on-screen texts of poems about exile and death, and chiaroscuro-lit sequences illustrating a Palestinian man’s attempt to cross the border and return home. Devoid of dialogue or voice-overs and played out to the eclectic sounds of atonal strings, electronic glitches, and traditional music, the film offers an expressionist reflection of the trauma of exile for nationless Palestinians across the Middle East and beyond.

Lebanese filmmaker Christian Ghazi’s A Hundred Faces for A Single Day (1971), meanwhile, is a riotous and irreverent stab at a Palestinian middle-class more concerned with sustaining their material comforts and their chauvinist family structures in Beirut than the state of things in their ancestral lands. True to its title, the film morphs its stylistic tenor repeatedly, as poetic sequences (of abandoned landscapes or injured civilians in hospitals, for example) give way to more realist (and sometimes even comical) scenes making up a multistrand narrative about the pursuit of art and national liberation.

A Hundred Faces for A Single Day (1971)

On-screen militancy is also very much absent in the seven shorts of the Exploding India section. Rather than focusing on documentaries exploring the Maoist-Naxalite insurgency sweeping across the rural backwaters of the country from the late 1960s onward, this sub-program highlights the work produced by the Films Division, which is part of India’s information ministry and the country’s post-independence equivalent to Britain’s GPO Film Unit. Playing fast and loose with their assignments, these nominally government-employed directors deploy avant-garde techniques to advocate their audacious arguments about a nation struggling to confront its own changes and challenges.

I Am 20 (1967)

This uncertainty is best manifested in S.N.S. Sastry’s I Am 20 (1967). Marking the twentieth anniversary of Indian independence, the film gauges the state of the South Asian nation through interviews with twenty-year-olds from widely varied backgrounds. Interwoven with a dizzying wealth of images symbolizing what a voice-over describes as India’s “precarious today,” Sastry’s piece offers a remarkably vivid account of a country where people live in markedly different circumstances and aspire to extremely different things. In a sequence typical of the film, three individuals talk about what they want: a young farmer dreams of a tractor; a spoiled scion seek pop records; and an office worker dreams of getting fifty saris for his bride.

I Am 20 (1967)

S. Sukhdev’s And Miles To Go… (1967) begins with a proclamation about the film’s dedication to “back the government’s efforts in tackling violence and problems of the country.” The film then launches into a series of montages contrasting the yawning gap between different social classes. The rich spend their mornings smoking pipes and drinking coke in their swank condos, while the downtrodden wake up in a cramped hut, line up for water, and struggle with their livestock. Music is entertainment at rooftop parties, background noise in a factory, and the sounds to which a performer slashes himself in public for loose change. But the documentary reverts to official propaganda toward the end, as a pompous voice-over calls on people to “defeat the demons of greed and corruption” by “invoking the conscience and action in all walks of life.”

And Miles To Go… (1967)

These films depict India as a young nation still grappling with the need to establish its own identity two decades after the end of British colonial rule. On another level, they also reveal the attempts of a new generation of filmmakers in establishing their own postcolonial voices, as they aspire to accommodate modernity with their own distinct historical traits. Pramod Pati’s Explorer (1968) and Trip (1970), which were also shown at the Réel, offer a complete break from traditions with its dazzling psychedelic visions of Indian urban and youth culture. Sastry, however, has doubts with that: in the self-reflexive And I Make Short Films (1968), the filmmaker ponders whether films, as argued by modernists, are merely art, or whether they are also sociological products. On this, the jury is still out.

Sara Gómez

Running against the dominant 1968 narrative, the Indian Films Division directors sought to question the very political and social system they were somehow supposed to extol. In Cuba, Sara Gómez was doing the same with her documentaries about certain aspects of society that Fidel Castro had somehow failed to reform. Made in 1969 and released in 1972, My Contribution (Mi aporte) highlights the struggle to achieve gender parity in a highly chauvinistic society, with women’s input—as workers, wives and mothers—being ignored or exploited by their unsympathetic colleagues or useless husbands. But the documentary takes a self-reflexive turn in the end: echoing what Jean Rouch did in Chronicle of a Summer (1961), Gómez added a coda in which her interviewees debate the points they and their fellow interviewees made in the film. These dynamic exchanges allow the women to foster some kind of solidarity among themselves, and also allow them to contribute to Gómez’s filmmaking process.

I Am Somebody (1969)

At the Réel, My Contribution is part of a three-film section titled Womanists. Of the other two films, Madeline Anderson’s I Am Somebody (1969) is similar in its demands for the recognition of women in political struggles through the depiction of the strike of black hospital workers in Charleston, South Carolina. The majority of these workers were women, and Anderson filmed them protesting against the authorities, braving violent assaults by the police, and also sitting together to strategize their action and analyze the current political situation. Focusing on a fight where race and gender converged, the documentary returns her doubly oppressed subjects to the center of a Civil Rights struggle where men were usually pictured in the lead.

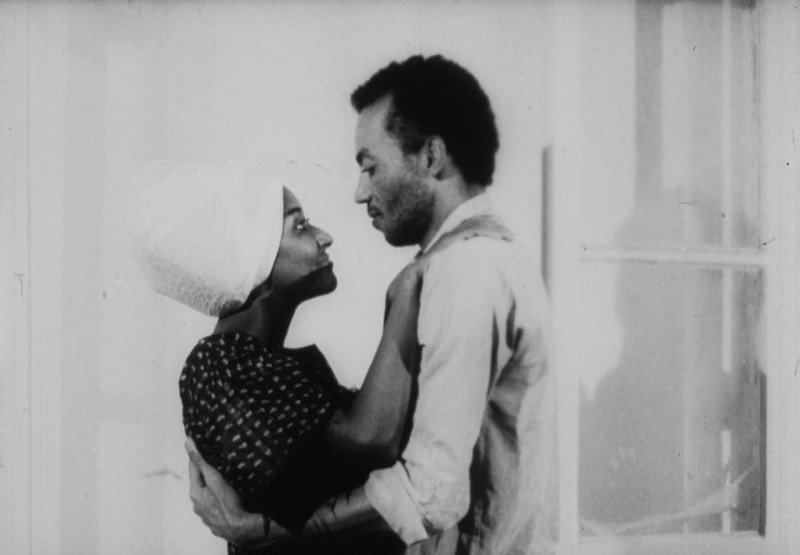

But the third entry of the section is perhaps best in revealing the global connections at work in 1968. A lyrical film revolving around the suffering of an Angolan freedom fighter in a Portuguese colonial jail, Monangambeee (1968) was the directorial debut of the Moscow-educated Guadaloupean-French filmmaker Sarah Maldoror. Designed to champion the anticolonial struggle in Africa, the film was made with the support of the Algerian government and the Conference of National Organizations of the Portuguese Colonies, and featured a soundtrack by the Art Ensemble of Chicago.

Monangambeee (1968)

Speaking of the border-transcending, genre-bashing nature of her first film, Maldoror—who was once married to the Angolan poet Mario da Andrade, and also worked with Chris Marker in establishing a film institute in Guinea Bissau—was quoted as saying how she is “from everywhere and nowhere.” With her multiple roles in the political and artistic revolutions emerging in the 1960s, Maldoror’s pedigree and perspective bears testimony to the internationalist dimensions of 1968 and the political movements to follow.

Clarence Tsui is a Hong Kong-based journalist and film critic who contributes to The Hollywood Reporter, South China Morning Post, and Film Quarterly. He also teaches at the Chinese University of Hong Kong and serves as an international consultant for the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival.

Copyright © 2018 by Cineaste Magazine

Cineaste, Vol. XLIII, No. 4