Sacco and Vanzetti (Web Exclusive)

Reviewed by David Sterritt

Produced by Arrigo Colombo and Giorgio Papi; directed by Giuliano Montaldo; screenplay by Fabrizio Onofri, Giuliano Montaldo, and Ottavio Jemma; cinematography by Silvano Ippoliti; production design by Aurelio Crugnola; edited by Nino Baragli; music by Ennio Morricone, with song by Ennio Morricone and Joan Baez; starring Gian Maria Volonté, Riccardo Cucciolla, Cyril Cusack, Milo O’Shea, Geoffrey Keen, Marisa Fabbri, William Prince, Rosanna Fratello, Claude Mann, Edward Jewesbury, and Valentino Orfeo. Blu-ray and DVD, color and B&W, with both Italian and English audio tracks, 125 min., 1971. A Kino Lorber release.

Just under a century ago, the world reacted with horror to the deaths of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti in the electric chair of a Boston prison. Working-class Italian immigrants who followed the teachings of radical anarchist Luigi Galleani, they were put to death in August 1927 after being convicted of murder in a 1920 trial so outrageously flawed that the verdicts sparked protests, strikes, and riots across the United States and around the globe. As their execution approached, tanks were sent to guard the American embassy in Paris, Swiss citizens attacked shops selling American products, the American flag was burned in South Africa, and outcries arose in Asia and South America; afterward 100,000 mourners filed past their electrocuted bodies in the mortuary where they lay before cremation. Although the kind of xenophobic bigotry that led to their death sentences has hardly subsided since then, the furor that erupted in the Twenties is hard to imagine amid the political apathy and inward-gazing nationalism of our own day. This makes the renewed availability of Giuliano Montaldo’s 1971 docudrama Sacco & Vanzetti all the more welcome. The film falls short of greatness, sketching the Sacco and Vanzetti case in a simplified and sometimes simplistic manner, but Kino Lorber’s edition (made from a 4K restoration) provides a grim reminder of the evils that can ensue when a judicial system goes belligerently off the rails.

Riccardo Cucciolla as Nicola Sacco (left) and Gian Maria Volontè as Bartolomeo Vanzetti (right).

Two outbursts of violence open the story: the Palmer Raids, a series of Justice Department attacks targeting people suspected of disruptive leftist sympathies in 1919 and 1920, and the death of Andrea Salsedo, an anarchist who “jumped” from the fourteenth floor of a New York City building where he was held and interrogated for weeks about a string of political bombings in 1919. These events are still fresh when Sacco (Riccardo Cucciolla) and Vanzetti (Gian Maria Volonté) are arrested and charged with murdering two employees carrying payroll money in Braintree, Massachusetts, a Boston suburb. Bewildered and terrified, both men lie to their captors, claiming to have no weapons or links to anarchism, although both have handguns with them and are quickly shown to be active in the anarchist movement. They have good reason to lie, as Montaldo indicates with repeated shots of Salsedo plummeting to his death, a fate that could easily await them as well. Instead, they go on trial, facing a judge named Webster Thayer (Geoffrey Keen), an enemy of subversives who also despises Italian immigrants. The prosecution is headed by Frederick Katzmann (Cyril Cusack), a county district attorney; in the actual case Sacco and Vanzetti had different defense counsels, but Montaldo’s version puts most of the burden on Fred Moore (Milo O’Shea), a firebrand from the radical Industrial Workers of the World who scandalizes the judge by wearing sandals and repeatedly mouthing off.

Anti-immigrant protests.

The courtroom proceedings resulted in guilty verdicts followed by years of appeals and pleas for a new trial. Even the film’s highly condensed account gives a vivid idea of the wildly conflicting eyewitness testimonies, mountains of ambiguous evidence, and barely concealed prejudices that piled up innumerable causes for reasonable doubt; moreover, a convicted criminal named Celestino Medeiros (Valentino Orfeo) confessed to the murders in 1925 and said Sacco and Vanzetti had nothing to do with them. But nothing budged Thayer, who rejected every appeal, and nothing swayed the tribunals that might have recommended a retrial. Although informed opinions vary to this day as to whether Sacco and/or Vanzetti committed the Braintree crimes, the rampant defects of the trial and its aftermath are indisputable. Anyone reading the transcript of the case, Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas accurately remarked years later, “will have difficulty believing that the trial with which it deals took place in the United States…The game was played according to the rules. But the rules were used to perpetuate an awful injustice.”

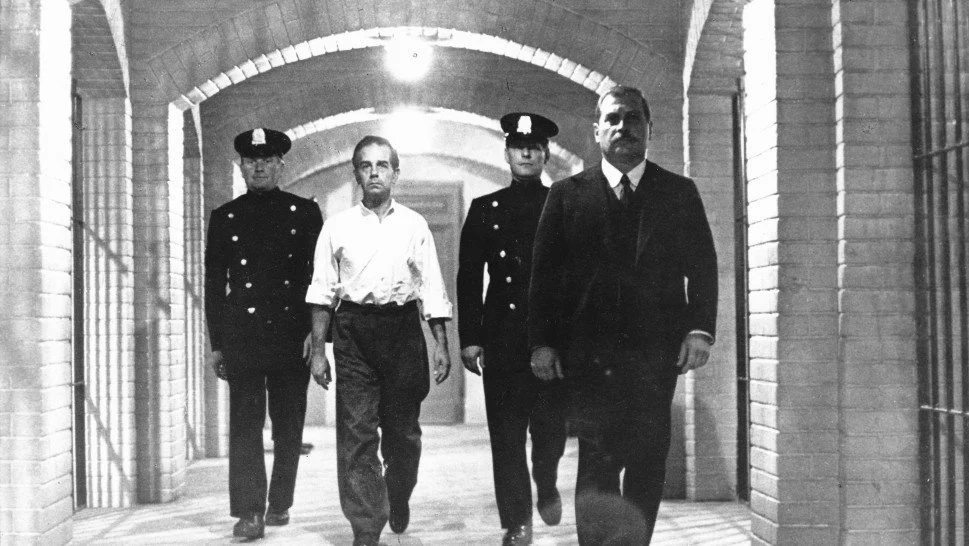

Sacco on his way to the electric chair.

Sacco & Vanzetti tells its story with restraint. It begins and ends in the black and white of a traditional newsreel, keeps to a low-key color scheme in other scenes, and energizes the many courtroom episodes with smooth, unshowy camera movements. The multinational cast was evidently chosen to bolster ticket sales in multiple countries; the title roles are played by Italians while Cusack and O’Shea hailed from Ireland, Keen came from England, and William Prince, who plays the late-arriving defense lawyer William Thompson, was an American known mainly for television roles. Unsurprisingly for an Italian-French production with an Italian director, all the voices are dubbed, and the Kino Lorber disc provides both the Italian and English dialogue tracks; to my ears they’re about equal in acting quality, although Volonté’s climactic speech and O’Shea’s escalating emotionalism should certainly be heard in their native tongues. As a Bostonian in bygone years, I also appreciate some of the broad New England accents on the English-language track; whoever dubbed Marisa Fabbri’s performance as the unreliable witness Mary Splaine got the lingo exactly right. Ennio Morricone’s music fits well with the film’s temperate visual style, and his score is supplemented by two songs he co-wrote with Joan Baez, who sings them during interludes in the story and behind the closing credits. They’re not major offerings, but their High Seventies sensibility has nostalgic appeal.

A years-long process with a highly charged historical background is a lot for a single film to handle, and although Sacco & Vanzetti clocks in at more than two hours, it alters, abridges, or omits a good deal of necessary material. The two defendants are frequently shown together, so you’d never guess they were locked in separate prisons and rarely saw each other; nor does Montaldo depict their hunger strikes or give much sense of their prison conditions, which were especially ghastly for Sacco, a vigorous man driven to despair by endless days of enforced inactivity in a tiny, stifling cell. Completely missing is Vanzetti’s trial and conviction for attempted murder in a slightly earlier crime, for which he was serving time when his joint trial with Sacco took place. The court’s incredibly messed-up handling of physical evidence is ignored, and while Montaldo’s terse execution scene gives the film a bluntly effective conclusion, I wish he had included Vanzetti’s last-minute forgiveness of “some [of the] people” who pursued and condemned him. It was a remarkable statement, made just moments before the current surged through his body.

Prosecutor Fred Moore (Milo O’Shea).

For the disc’s audio commentary, Kino Lorber has turned to filmmaker Alex Cox, an interesting choice but not an excellent one. Since one of his first remarks is conspicuously wrong—the 1967 heist movie Grand Slam was not Montaldo’s first feature, as Cox avers, but his third—one can only hope that his other factual statements are more accurate. Cox also lapses into silence quite often, blaming this on the movie’s copious length, as if 125 minutes were a very tall order. These caveats aside, he gives a useful précis of the production, which was shot mainly in Yugoslavia, with additional scenes filmed in Italy and Dublin as well as Boston, where the Braintree robbery and murder were re-enacted in their actual locations. It took two years for Montaldo to find producers for the project because news about the Sacco and Vanzetti trial had been heavily censored by the fascist regime in Italy, and the case was virtually unknown there when he began looking for funding and support; a breakthrough came when he realized that Grand Slam producer Arrigo Colombo, who fled Italy for America in 1937, had practiced his English-language skills by reading the published edition of letters Vanzetti wrote to his defense committee. (Sacco & Vanzetti carries the banner of Jolly Film, the legendary production company founded by Colombo and Giorgio Papi in 1964.) Signing the high-powered Volonté was another coup, especially since the star was himself an activist for leftist causes, and Montaldo insisted on him when the French coproducers lobbied for Yves Montand, who had equally strong credentials as actor and activist but lacked the Italian identity that made Volonté a perfect candidate. Beyond particulars like these, Cox’s commentary suggests a lack of deep thought about the material. He finds it “quaint” that Massachusetts calls itself a commonwealth instead of a state—does that go for Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Kentucky, too?—and he thinks Vanzetti’s first trial and conviction are negligible details that the film justifiably leaves out. To the contrary, that very relevant proceeding also took place before Thayer, whose unusually harsh sentencing foreshadowed his hostility toward the defendants in the more notorious case that followed.

The real-life defendants.

On the bottom line of whether the ill-fated anarchists were in fact guilty, Cox claims that the most recent research points to innocence for both. He doesn’t specify what research he’s referring to, but there is nothing like unanimity on this matter. In his 2007 book Sacco and Vanzetti: The Men, the Murders, and the Judgment of Mankind, perhaps the definitive analysis of the case, Bruce Watson runs through arguments in both directions, giving a formidable list of never-resolved questions about inconsistent timelines, murky motivations, missing money, and plenty more. Numerous other authors have weighed in with books over the years, most of them coming from the left and declaring the defendants innocent, as do the fiery Howard Fast in The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti, the highly personal Katherine Anne Porter in The Never-Ending Wrong, the angry John Dos Passos in Facing the Chair and the mighty U.S.A. trilogy, and the logorrheic Upton Sinclair in Boston: A Documentary Novel. More recently, some observers have concluded that Sacco was indeed culpable, Vanzetti not. The debate may never end.

Apart from Montaldo’s film, moviegoers interested in the case can choose from such undistinguished options as Terry Green’s 2013 drama No God, No Master, with David Strathairn as a federal agent investigating the case, and Peter Miller’s 2006 documentary Sacco and Vanzetti, where historian Howard Zinn is among those in the emphatically-not-guilty camp. Against this competition, Montaldo’s picture is the easy winner. As film historian and Cineaste editor Richard Porton has persuasively shown, Montaldo is more concerned with eliciting sympathy for his eponymous martyrs than with explaining their anarchist principles or probing the full implications of their belief in “propaganda by the deed” at a time when political violence was far from rare. Yet his movie is well worth viewing for its earnest denunciation of anti-immigrant biases, bigoted power brokers, and out-of-control judiciaries in an era not altogether different from our own.

David Sterritt is editor-in-chief of Quarterly Review of Film and Video, film professor at the Maryland Institute College of Art, and author or editor of fifteen film-related books.

Copyright © 2022 by Cineaste Magazine

Cineaste, Vol. XLVII, No. 4