Buster Keaton DVDs (Web Exclusive)

Reviewed by Randall Conrad

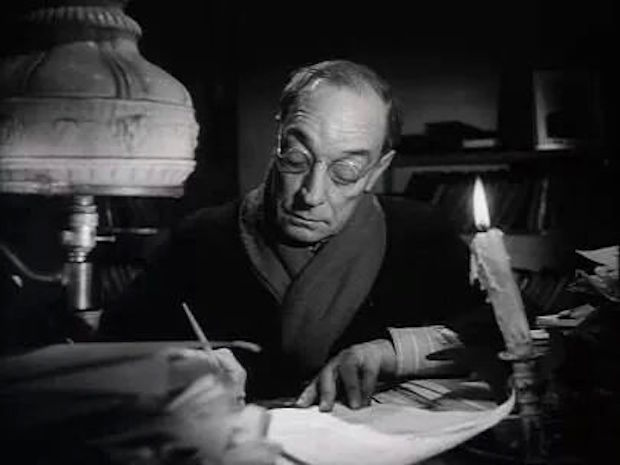

Buster plays it straight in The Awakening

Two DVD releases from Kino Video.

Lost Keaton: Sixteen Sound Comedy Shorts (1934-37), a two-DVD set, approx. 306 min., and Keaton Plus (1921-1962), approx. 200 min.

Ah, Buster Keaton! His feature-length silent comedies, produced mainly by his own studio during the 1920s, now rank as the greatest work ever done in that form, easily rivaling (and artistically outranking) Charlie Chaplin.

Viewed today, Keaton's features—Our Hospitality, The Navigator, The General, and Steamboat Bill, Jr., among others—are among the most beautifully photographed and stylistically modern films of the entire silent era. The General (1926), Keaton's Civil War locomotive chase epic, is the highest-ranked silent film in the AFI's hundred-greatest poll.

Keaton pioneered his own comedy of the absurd, capturing the pervasive aura of aloneness and mystery that haunts contemporary life. His silent masterpieces juxtapose an unpredictable world against one tiny individual whose reactions to it are always logical. Keaton performed all his own stunts, some of the most fascinating and hilarious feats of muscle, wit, and timing ever filmed. He risked his life swinging over waterfalls, plunging into chasms, and being hurled through seething rapids. Keaton eschewed using a stunt double or the standard editing tricks. “We get it in one shot or we throw out the gag,” he would say—for this visual unity helps to sustain our suspension of disbelief, making the physical comedy more thrilling.

The core of Keaton’s characterizations, and his comedies, is human fulfillment. In his features, he often played (as he said), “a really useless young millionaire who can’t even shave himself.” In the course of events, the callow youth would discover love, competence, and courage. Keaton's last independent production, Steamboat Bill, Jr. (1928), is an archetypal father-son tale: Buster's effete college boy grows into a man while comically battling a devastating cyclone on the Mississippi, managing to rescue both his father, a tough steamboat captain, and his girlfriend, the daughter of dad's business rival.

Keaton's silent features themselves are available as a box set of eleven DVDs from Kino (2001) titled The Art of Buster Keaton. (The eleventh volume is none other thanLost Keaton.) After the grandeur of his silent features, Buster was brought low during the Depression by a perfect storm—one, changes in the film industry and in the medium itself with the advent of the talkies; and two, an emotional maelstrom worsened by advanced alcoholism. Working now for MGM, Keaton lost creative control. (His last good feature was The Cameraman, 1929.) At the same time, he succumbed to devastating symptoms of an alcohol addiction that had previously been held in check by the hyperactivity of his creative life. He ruined his marriage and racked up large debts.

Even after Keaton had sabotaged his life and career options, however, he continued to work in film. During the Thirties, notably, he appeared in a number of two-reelers (twenty-minute comedies) of uneven quality. Until very recently, most historians had no chance to watch these shorts, even after the restoration and redistribution of Buster's silent classics in the 1960s, but had to rely on secondhand summaries instead.

As a result, Keaton's creative decline has been misunderstood and misrepresented by earlier biographers. He was "wasted in cheap shorts," thought William K. Everson (1967). "It was like lightning felling the oak... Buster Keaton was annihilated. He was vanquished," Robert Benayoun expostulated in 1983.1

In contrast, James L. Neibaur argues in The Fall of Buster Keaton (2009) that, "the 'MGM and after' efforts are not always the complete disasters that their reputation would have some believe... The better films from this period of his career have significant Keaton touches that bolster their critical value."

In particular, a number of short comedies Keaton made for a poverty-row studio named Educational Pictures (all collected on Lost Keaton) bear out Neibaur's claim. In these two-reelers, Buster, who sometimes contributed uncredited gag writing and directing, is at his finest when he is simply wrestling with everyday props—stepladders, folding chairs, fishing tackle, pistols, loose planks and breakaway furniture—as in the silent days. The Gold Ghost (1934, in which Keaton becomes the sheriff of a ghost town), features a number of nice gags culminating in a free-for-all and gunfight as the town is repopulated by tourists in a second gold rush. Although many of the gags in these extra-low-budget pictures depend on editing, a few are achieved in a single, unbroken take, obedient to Keaton's golden rule when he was master of the silent feature.

Keaton Plus, the other Kino DVD, includes short films (with two or three repeats from Lost Keaton), including the prelapsarian Hard Luck (1921), a recently restored two-reeler in which Keaton attempts suicide in various comedic ways. Keaton Plus also includes scenes from a 1951 TV series whose production credits include erstwhile Keaton collaborators. Worth a watch is Buster performing a tango with a female co-star, who stands a head taller, in an excerpt from Detective Story. Other TV clips include an "informational film" and other commercials in which Keaton's stunts sell gasoline, motor oils, instant photography, and beer. The DVD also has a "Locations" section that takes us to the exact premises Keaton used in Cops (1921) and The General, based on the book Silent Echoes: Discovering Early Hollywood through the Films of Buster Keaton (2000, www.SilentEchoes.net) and narrated by its author, John Bengston.

One item of passing interest from the McCarthyist years is a half-hour teleplay that was produced on Douglas Fairbanks Jr. Presents, a TV series that ran from 1953 to 1957. The Awakening (1954) is the tale of a humble clerk (Keaton in a straight dramatic role) who dares to rebel (successfully) against a 1984-style bureaucratic dictatorship, exposing "what could happen if a man forgets the true meaning of freedom and sacrifices himself on the altar of regimentation," in the bombastic words of the program's introduction.

- Tom Dardis's exceptional Keaton: The Man Who Wouldn't Lie Down (1979), remains a sensitive and scrupulously researched biography. Dardis traces Keaton's deadpan ability to absorb physical pain to its origins in abusive treatment at the hands of an alcoholic father. This included being tossed around the stage and into the audience as part of the family vaudeville act. Dardis also argues that "it was the financial failure of Buster's best work that stifled his creative freedom at the beginning of the sound era. It has been widely believed that Buster's sound films for MGM were financial failures compared with his great silent films; in fact, the reverse is true." Buster's masterpieces The General and Steamboat Bill, Jr. both bombed at the box office, while the MGM productions made decent money—proof (to the moguls) that MGM knew best how to build vehicles for the recalcitrant comedian.

Randall Conrad is a former Contributing Editor to Cineaste.

Click the titles to purchase Lost Keaton and Keaton Plus.

Copyright © 2011 by Cineaste Magazine

Cineaste, Vol. XXXVI, No. 2