Videodrome (Web Exclusive)

Reviewed by Royal S. Brown

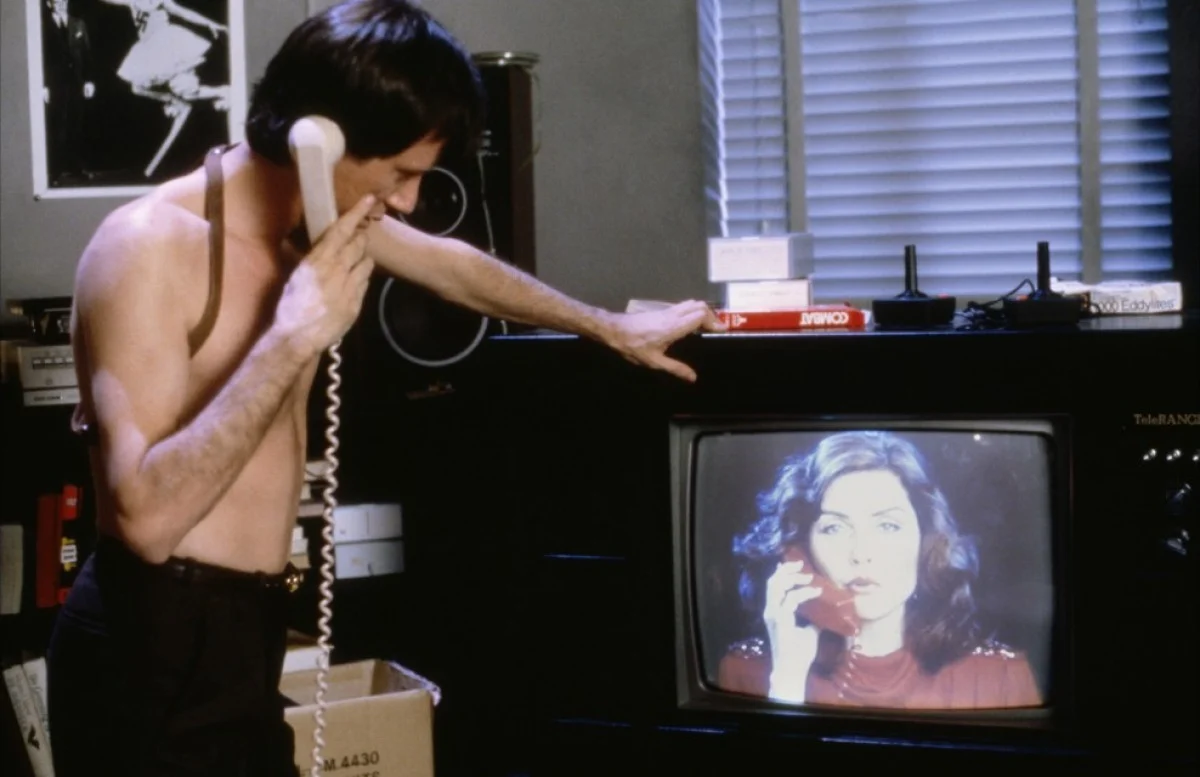

Deborah Harry as radio host Nicki Brand speaks to Max (James Woods)

Written and Directed by David Cronenberg; produced by Claude Héroux; photographed by Mark Irwin; edited by Ronald Sanders; music by Howard Shore; starring James Woods, Deborah Harry, Sonja Smits. Blu-ray, color, 89 mins., 1983. A Criterion Collection release distributed by Image Entertainment.

On one of the two audio commentaries available on this Blu-ray disc of Videodrome, actor James Woods, who plays the movie’s demanding main role, uses the words “philosophical, theological, and sociological” in an attempt to define the various intersecting layers that the attentive viewer/listener can discern in this thoroughly bizarre but utterly brilliant sixth feature film from Canadian writer/director David Cronenberg. It is in fact difficult to separately address each of these layers—to which I would add a fourth and fifth, “political” and “psychological”—when writing about Videodrome, which focuses on the character of Max Renn (Woods), the coowner of a Toronto-based cable-TV station that is moving big time into soft-core pornography in order to attract a larger viewer base. In what can be considered the movie’s initial phase, Renn is seeking out films that will, in his words, “break through. Something tough.” He first auditions the last cassette of a thirteen-part series brought to him by two Japanese men. Although one of his partners feels that “Oriental sex is a natural,” his other partner does not find it tacky enough to turn him on, and Renn himself finds it too soft. Later he auditions—and rejects—an even softer Greek-themed tape brought to him by Masha (Canadian actress Lynne Gorman), an older woman with a foreign accent and a taste in much younger men.

In between these two fruitless searches, however, Max is introduced by his resident pirate, Harlan (Peter Dvorsky), to fifty-three seconds of video material that definitely piques his interest. Apparently transmitted by a satellite feed, the material shows nothing but a nude woman being chained to a pipe by two hooded men and then garroted by one of them. In a second visit to the pirates’ den Max sees another feed in which a black man hanging on chains has electrodes attached to his genitals by one black-hooded person while another whips him. The entire program, according to Harlan, is about nothing but “torture, murder and mutilation.” Renn, rather than being appalled, reacts enthusiastically: “It’s brilliant. There’s almost no production costs. You can’t take your eyes off it. It’s so realistic” (all of the movies-within-the-movie footage was shot specially for Videodrome). A bit later, as a belly dancer does her number in a Greek restaurant, Masha, hired by Max to investigate Videodrome, informs him that what he has seen is “snuff TV,” an idea that Max dismisses: “Why do it for real? It’s easier and safer to fake it.”

Now, even though Cronenberg, in his audio commentary, acknowledges the ideas of a fellow Canadian, media philosopher Marshall McLuhan, as a principal impetus forVideodrome’s narrative, the philosophy that this first phase in the writer/director’s cinematic vision engages more than anything else is, in my opinion, that of Jean Baudrillard, who spent much of his career examining the phenomenon of simulacra in contemporary culture. While Max pooh-poohs—strictly for practical, not moral, reasons, it should be noted—the need for “snuff” movies, in which the hideous acts taking place onscreen are purported to have been “real,” his quest for “something tough” is driven by the same desire that nurtures the fantasies of snuff movies, namely to bring the various signs that represent something “real” ever and ever closer to that reality. Put another way, there will theoretically be no distinction between the sign and what it represents (“Is it real, or is it Memorex?”). Baudrillard, in his 1985 article “L’an deux mille ne passera pas” (badly translated as “The Year 2000 Has Already Happened”), uses quadraphonic sound (remember that?) and hypergraphic pornography as blatant examples of attempts to realize this impossible dream.

But a funny thing happens as Max continues on his quest, becoming more and more obsessed with Videodrome, and this gets us into the Marshall McLuhan phase of the movie. While he is seeking a type of cinema in which viewers will see and hear onscreen action as real rather than as a concatenation of diverse audio and visual signs in motion, Max suddenly finds that his mind has been taken over by the Videodrome images he has been watching, which cause him to enter a world in which the line dividing what we presume to be reality from wild hallucinations of sex, violence, and physical transformation simply disappears. An absolutely essential quality of Cronenberg’s film is that it gives his viewer/listeners absolutely none of the usual cinematic cues—blurry images, weird music, things like that—which normally allow filmgoers to say, “Ah, that’s just an hallucination.” Like the film’s hero who, increasingly trapped in his mental states, appears in every one of Videodrome’s sequences, the audience finds itself trapped in a labyrinth of images and images of hallucinations made even more “real” by the extreme tactility of the special makeup and video effects from Rick Baker and Michael Lennick, respectively, which range from the unsettling—living and breathing video cassettes and television sets, for instance—to the downright gruesome—a vaginal slit that opens in Max’s stomach to receive living and breathing video cassettes or a pistol that becomes more and more organic; masses of yucky golfball-size tumors that spill out of the head and body of an assassinated victim.

There are two faces to this phase of Videodrome. One is that of Nicki Brand (Deborah Harry, the lead singer of the rock group Blondie, although she has sumptuous auburn hair in this picture), ironically the host of a radio help show, who introduces some solid moments of masochism, climaxing with her burning an extra nipple onto her breast with a lit cigarette, into her graphic lovemaking scenes with Max. As the movie presents it, this sexual activity, along with the Videodrome images, helps open channels in Max’s mind that make it more susceptible to the invasion of video images. But there is a much more sinister side to this invasion, a second face, if you will, and that’s where the film’s political layer comes in. As it turns out Videodrome is the creation of what Cronenberg refers to in his commentary as a group of moral right-wingers that include Harlan and a businessman improbably named Barry Convex (Les Carlson). Their goal is to use the hallucinogenic Videodrome signal to infiltrate the minds of viewers across the continent so that the entire North American population can be controlled by the political agenda of a power elite. Cronenberg notes that he based the Barry Convex character on televangelists such as Jim Bakker, whom he refers to as “sinister” and “dangerous,” and, after his sex scandal and conviction of accounting fraud, as a “scumbag” and a “scoundrel,” “a man of the cloth bringing in the right people in order to eliminate them.” A starting point in this campaign becomes the takeover of Max’s TV station.

In this sense Videodrome turns out, as several have remarked, to be quite a prescient film. As the ever frank Cronenberg remarks, “It’s basically getting fucked by television, which I think everybody is.” As Videodrome metaphorically, but only somewhat metaphorically, suggests, audio/video images have become so prevalent that they have installed themselves as a permanent part of the human brain, resulting in a massive sociological reversal whereby it is no longer the outside world that inspires images but video images that shape and determine the way we perceive the outside world and conduct ourselves, often violently, within it. Since, of course, we are dealing with a filmic narrative, something of an apocalyptic battle becomes all but inevitable, which brings us to Videodrome’s third phase. Standing against the fascists who want to take control of the North American mind via a psychologically crippling video signal is one Bianca O’Blivion (Sonja Smits), daughter of the film’s McLuhan figure, Brian O’Blivion (Jack Creley), a media philosopher who allows himself to be seen on television only on television. Bianca runs the Cathode Ray Mission (!), described by Cronenberg as the kind of cult that Marshall McLuhan would have established had he been so inclined. At this mission the down and out—the underclass that the conservative right is particularly eager to bring under total control—come and are shown to individual cubicles within which they watch television all day long.

One might think, of course, that this would feed right into the hands of Barry Convex and his crowd, particularly given the nature of the crap the down and out are watching. But the film takes a rather sophisticated philosophical turn here, a turn that somewhat brings together McLuhan and Baudrillard. One is to suppose, I think, that by being constantly exposed to the audio/visual image, the down and out, along with any others doing the same thing, will begin to experience the reality of the image (what the film ultimately calls “the new flesh”) rather than the image as reality. It is into this area that Bianca O’Blivion ultimately leads Max who, by the end of the film hopelessly trapped in his own mind, ends up in a condemned tugboat in the port of Toronto. His only salvation is to allow himself, with the guidance of Nicki, who shows up on a television set inside the tugboat, to become “the new flesh,” a concept that raises the McLuhan aphorism “The medium is the message” to a new level: the medium is the new flesh. The film concludes with an act presented as an image within the image, which is then identically repeated as an image on the movie screen. This represents the final undoing of the linearity of the signifieràsignified relationship that is at the very base of media manipulation.

As far as I am concerned Videodrome is David Cronenberg’s masterpiece, and I am a huge fan of just about all of his movies. In some ways the film is consistent with a vision that runs through much of the writer/director’s work, namely the body reclaiming, sometimes in very yucky ways (one thinks immediately of the exploding heads in Scanners), its autonomy in a world whose inhabitants are constantly attempting to isolate it from the mind. But at the same time that much of Videodrome comes across as a low-budget sci-fi/horror film, it offers a profoundly complex vision of the philosophy of the image that ultimately can be understood only via the carefully constructed images of the philosophy of images brilliantly created across the body of the film. In a wholly different area Videodrome also offers viewers an engaging and sometimes depressing portrait of 1983 Toronto, a city all but unknown to the cinema at the time but that has now become one of the world’s film capitals. The final sequence, shot at the port of Toronto in early winter, offers one of the most visually bleak landscapes to be found anywhere in the movies. It is a landscape that mirrors what Max Renn’s mind has become by the end of the film.

Adding to the film’s depth is the mostly synthesizer score by Howard Shore, described by Woods as “almost an electronic version of Bernard Herrmann.” “Almost” is the key word here, because just as Max wanders in a no-man’s land somewhere between the inner and the outer worlds, Shore’s often morbid musical strains fall, unlike most of Herrmann’s, somewhere between tonality, via which most people in the Western world still measure their sense of musical reality, and atonality. The principal timbres are a synthesized string orchestra and a synthesized church organ, the latter often playing simple but dissonant intervals in unison. But there is one extended quasistrings cue, which I would label a rhapsody, heard initially during the first lovemaking sequence and then returning behind the end titles, that drones its way slowly and very sadly through minimally shifting harmonies that seem to extend out and beyond that extraordinarily bleak horizon we see in the last sequence.

Max's body reacts to the effects of Videodrome

This is one of film music’s finest productions.Criterion’s Blu-ray disc definitely has that breathtaking clarity one is beginning to take for granted in this medium, although I do find some of the scenes on this transfer darker than I remember them from other viewings. The disc also offers numerous extras, including two separate audio commentaries that are both interesting and revealing, should you opt to run them with the film. One is by Cronenberg and director of photography Mark Irwin, the other by James Woods and Deborah Harry. But the absolute gem amongst the extras is a seven-minute short entitled Camera that Cronenberg created for a collective film entitled Short6, released in 2001. In this film an older man (Les Carlson, who plays Barry Convex in Videodrome) pessimistically muses on how the media are instruments for recording aging and death (“When you record the moment you record the death of the moment”), this in response to a full-blown Panavision 35mm movie camera wheeled into his house by a group of children.

Most of the film is shot in video, and includes a number of pretty grotesque close-ups. But as the character continues to relate his very dark philosophy the children form a complete film crew, cleaning the contacts, setting up the boom mike, combing the character’s hair and checking his makeup, bringing the camera into his room, etc. By the end a young boy who has become the director calls out “action,” at which point the film switches to a glorious 35mm image, complete with a musical snippet from Howard Shore, as the old man begins all over again with the lines that opened the film. It brought tears to my eyes.

To purchase Videodrome, click here.

Royal S. Brown is a professor in the City University of New York. He is the author of numerous articles and reviews. He is currently preparing two books, including a series of interviews with composer Howard Shore and analyses of some of his scores.

Copyright © 2011 by Cineaste Magazine

Cineaste, Vol. XXXVI, No. 2