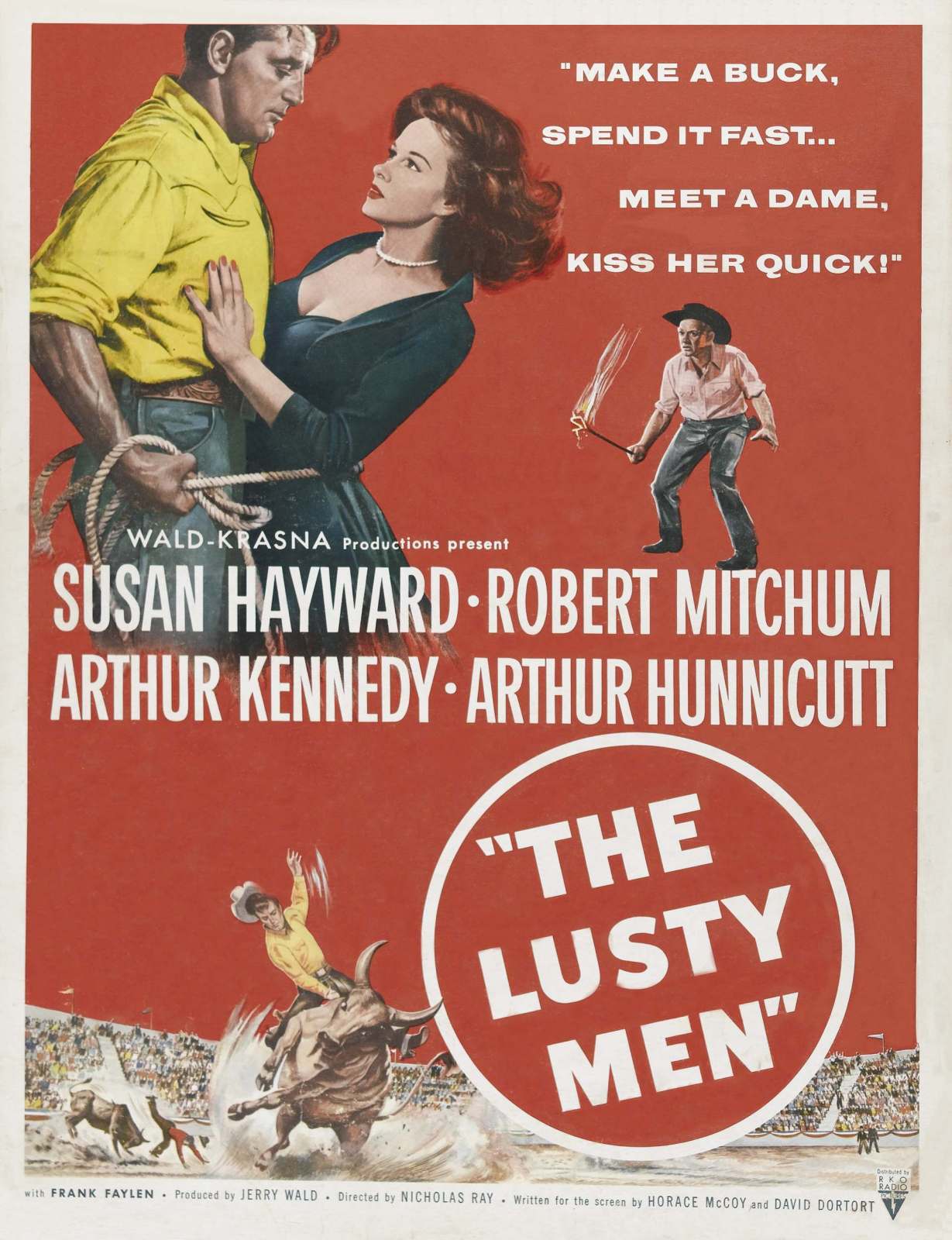

The Lusty Men (Web Exclusive)

Reviewed by Leonard Quart

Produced by Jerry Wald; directed by Nicholas Ray; screenplay by Horace McCoy and David Dortort; suggested by Claude Stanush’s story; cinematography by Lee Garmes; edited by Ralph Dawson; sound by Phil Brigandi; art direction by Albert S. D’Agostino and Alfred Herman; music by Roy Webb; starring Robert Mitchum, Susan Hayward, Arthur Kennedy, and Arthur Hunnicutt. DVD, B&W, 113 min., 1952. A Warner Archive Collection release, http://www.wbshop.com.

Nicholas Ray was an original—an emotionally intense, visually inspired, and self-destructive American director who was at war his entire working life with the artistic compromises demanded by the Hollywood studios. His best works, They Live by Night (1948), In a Lonely Place (1950), Rebel Without a Cause (1955), andBigger than Life (1956), were suffused with a romanticism that centered on lonely, wounded outsiders at odds with American middle-class values, like familial domesticity, that dominated their lives. These films conveyed a passionate sympathy for the alienated and the marginal, with whom Ray clearly identified. Still, like many great Hollywood directors of his era, most of his films involved a variety of studio assignments and genre films. To express his personal vision and style he had to find artistic space amidst the narrative conventions and commercial demands of the industry. More often than not he succeeded, but at great emotional cost. Toward the end of his life, Ray became increasingly difficult to work with, developing a serious dependence on drugs and alcohol and a reputation for instability. He retired from commercial filmmaking after directing two epic films in Spain.

The Lusty Men (1952) was an early work of Ray’s, shot in striking black and white by cinematographer Lee Garmes, that takes place in the very male subculture of rodeos and its participants. One of the film's strengths is its central character, Jeff McCloud, a sleepy-eyed, laconic, calmly masculine, and charismatic Robert Mitchum in one of his strongest performances. McCloud is a former rodeo champ who has dissipated his winnings on gambling and women, and after being injured by a bull has left the circuit penniless. After nearly twenty years away, he has drifted back to his boyhood home in Texas. Ray depicts McCloud’s departure from the rodeo with a stunning melancholy long shot of him limping in a desolate field with papers blowing about, while on the soundtrack we hear the wind whistling through the emptiness. Reaching his old home—a shack—he finds a toy gun, a cowboy magazine, and a tobacco tin in which he used to keep his money. That’s all that remains of his past, and the film seems to convey, for just one moment, that Jeff may feel some regret for the life choices he has made.

Jeff meets a married couple, the fiery, sharp-tongued, redheaded Louise (Susan Hayward) and Wes (Arthur Kennedy), a poor but ambitious cowhand. Their dream is to buy a ranch, and Wes calculates that Jeff could be the mentor who will turn him into a rodeo champ, enabling him to make some quick cash. Wes turns out to be a natural and, despite Louise’s objections and fears, becomes a star on the circuit.

The tense triangular relationship between Jeff, Wes, and Louise centers the film. Wes’s sudden celebrity goes to his head, he forgets about his dream of a ranch and begins to live high, to play around with other women, and to reject Jeff and the sound advice he offers. A frustrated Louise begins to confide in Jeff, who has fallen in love with her. It’s all rendered in a low-key, natural manner, without melodrama or tearful scenes. Louise may be attracted to Jeff, but her enduring commitment is to Wes, who holds out the only hope of something solid and rooted in a life that from childhood has been fragmented and impoverished. It’s the Fifties, and marriage is the only option that a woman like Louise can conceive of to give some meaning to her life.

Robert Mitchum as former rodeo champ Jeff McCloud

Ray’s deepest sympathies are for outsiders, not for those who choose domesticity. But the film doesn’t sentimentalize the rodeo ethos and its peripatetic participants. Using documentary footage, the film provides us with a detailed and seamlessly integrated portrait of the stadium ambience: the pageantry touched with patriotism, the rodeo clowns and trick riders, and the calf roping and bronco and bull riding, where the contestants get scarred and crippled, and a few even die. It’s rare that any one of them ends up with much to show for their efforts. There are no real winners in the rodeo.

It’s also a swaggering male world where heavy drinking, womanizing, and hard partying are the norm, and it’s dominated by a kind of foolhardy macho fearlessness and stoicism. While the men’s wives and girlfriends sit in the stands through the events, rooting for their men and hoping they come out unscathed, life on the circuit is transient and often mean. Most of the contestants live in small trailers where family life is close to impossible. Aside from Louise, however, most of the women bear the difficulties and dangers of the life with little complaint.

Notwithstanding, Ray is sympathetic to the men, who revel in the applause of the crowd and are willing to risk their lives for small rewards. His heart goes out to those who wander endlessly, like Jeff, who love the rodeo life. Jeff has his flaws, but he conveys a touch of nobility—more so than any of the other characters in the film.

The Lusty Men concludes on a relatively realistic note—Jeff dying in a rodeo accident, and Wes reaffirming his respect for him (“He was the best”), and abruptly quitting the circuit and heading back with Louise to Texas and ranching. Ray, however, had to fight the producer and the studio to conclude the film the way he wanted. They pushed for a Hollywood-style sentimental finish with Jeff surviving and going off into the sunset with an ex-girlfriend. Ray’s ending is truer, and there is no happy future in the offing for any of the characters. Louise and Wes have chosen a more secure and tedious, but less autonomous and adventurous life. From Ray’s perspective, nobody wins in a film where one feels a gloomy fatalism underlying all the action. The Lusty Men is a small, poetic film with an emotional resonance that goes beyond its bare narrative.

Leonard Quart is the author or co-author of several books on film, including the fourth edition of American Film and Society Since 1945.

To purchase the Warner Archive DVD of The Lusty Men, click here.

Copyright © 2015 by Cineaste Magazine

Cineaste, Vol. XL, No. 2