Becoming Visionary: Brian De Palma's Cinematic Education of the Senses

Reviewed by David Greven

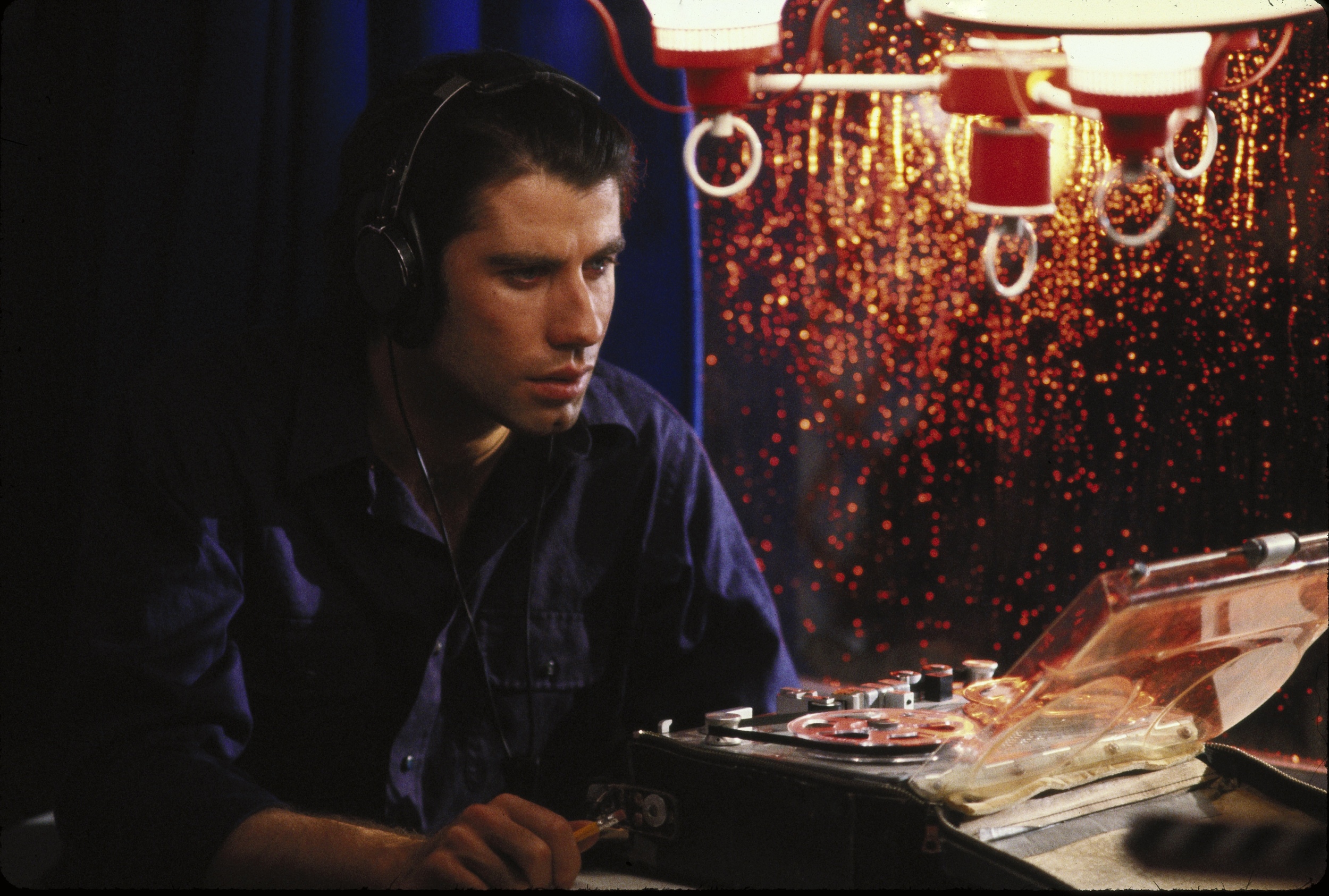

Blow Out

By Eyal Peretz. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2007. Hardcover: $55.00 and Paperback: $21.95.

In his exciting and innovative study, Becoming Visionary: Brian De Palma's Cinematic Education of the Senses, Eyal Peretz situates Brian De Palma's importance as a director within a philosophical and psychoanalytic framework of the gaze, arguing that De Palma's cinema allows us to understand the gaze not as mastery of vision but as a blinding rupture within vision itself. Fascinatingly, Peretz describes De Palma's cinema as "a laboratory attempting to isolate, demonstrate, and give a genetic account, in other words, a historical account, of the emergence of various defensive human gazes."

Peretz's book performs a vital intervention in the career assessment of Brian De Palma, in my view the most daring and original genius in American cinema after Hitchcock, but also one of the most critically maligned and, when not maligned, misunderstood of Hollywood directors, even by some of his most fervent supporters. Robin Wood, Kenneth MacKinnon, and Terence Rafferty, and, most famously but also most problematically, Pauline Kael, express admiration for De Palma in a way that is both stimulating and thoughtful. But they have done little to dispel certain misconceptions about him. For years, De Palma's work has been dismissed as misogynistic, on the one hand, and opportunistically derivative, on the other. About this latter point, De Palma's astonishingly productive and ongoing agon with the work of Alfred Hitchcock—commencing with the 1973 Rear Window homage Sisters and vividly on display in his recent masterpiece Femme Fatale —has been viewed by the general run of critics as plagiaristic and crass appropriation of the "Master of Suspense" by a talented but shallow hack.

Peretz's book is invaluable both for the insistent force of its belief in De Palma's significance as a great filmmaker and for the brilliantly incisive acuity of several of its insights on the study's own philosophical terms. For Peretz, De Palma is the "greatest contemporary investigator, at least in American cinema, of the nature and the logic of the cinematic image," which Peretz, following Lacan, describes as a "blankness at the heart of the senses." The three main chapters focus, respectively, on three of De Palma's most significant films: Carrie, The Fury, and Blow Out; the epilogue turns to De Palma's sumptuously oneiric Femme Fatale as a "paradoxical happy ending." The chapter on The Fury—one of the very greatest and most difficult, and also, most overlooked (except by Godard) of De Palma films—contains some particularly provocative and brilliant insights. However, the depth of coverage in these chapters comes at the expense of the opportunity to convey either the range of De Palma's cinema or its antic, avant-garde comedic origins. Nevertheless, Peretz's book is a bracing beginning to a new appreciation of De Palma's oeuvre.

Peretz articulates the methodological context of his book this way: "How is one to think through the significance of the art of film for philosophy? What would it mean to introduce film as a question for the philosophical enterprise?" This approach reaps the rewards of some dazzlingly suggestive insights into De Palma's cinema. Peretz provides a bravura reading of the great sequence in The Fury in which psychically supergifted Gillian (Amy Irving) has a staircase vision of her psychic twin; Peretz reads the entire sequence as a meditation on the experience of the cinema itself. Yet, brilliant as this sequence is, it is certainly secondary to the sequence in which Gillian, with help of some allies, escapes the imprisoning Paragon Institute. And for some reason, Peretz does not explore it as well, although it is a sequence in which De Palma fully realizes the disparate elements of his sensibility: a penchant for dreamlike lyricism, an appetite for sadistic shock, a prankster wit, and, above all, a rigorously mournful, tragic pessimism. Peretz's lack of attention to it—and to De Palma's staging of the prom sequence in Carrie—reveals a certain, a surprising, squeamishness about the director he aims to champion. One almost gets the feeling that Peretz is, on some level, as embarrassed by the director as are many of his detractors; Peretz focuses on the De Palma that can best accommodate his intellectualized take on the director.

In re-creating De Palma in the image of his theories, Peretz joins himself to one of the most unfortunate aspects of the history of criticism about this director. For example, one of the major frustrations of Pauline Kael's invaluable but vexing reviews of De Palma is her lack of appreciation for the tormented emotional investments of De Palma's films. This is not to suggest that she did not ultimately recognize the suffering in De Palma, but this recognition did not come about until her review of Blow Out . Her reviews of Sisters (De Palma's first masterpiece and first Hitchcockian homage, which she panned), Obsession (one of his most important films, dismissed by her in passing), Carrie, The Fury, and Dressed to Kill (1980) certainly conveyed the pleasurable aspects of De Palma's style, but they also cemented the view of De Palma as a fiendish cinematic prankster, gleefully raiding the "trash heaps" of popular culture. (It should be noted that her review of De Palma's anguished Vietnam War film tragedy Casualties of War [1989] is one of her very finest and most acutely sensitive reviews, and signaled a full recognition of the tragic nature of De Palma's vision.) Still, the extent to which De Palma remains a figure of critical opprobrium can be most clearly seen in the enduring ridicule Kael received because of her appreciation for De Palma's work. In a New York Review of Books account of her career, Louis Menand (with singular obtuseness) cites her highly positive review of De Palma's Blow Out as a "shameless rave" that evinced Kael's weakening critical powers.

One of the factors in Kael's celebration of this "prankster" De Palma was her own anti-auteurist dismissal of Hitchcock as primarily "an entertainer" (ironically enough, Andrew Sarris's own denunciation of Kael). Because Kael could not recognize Hitchcock's own genius as a director, much less the urgency of his directorial obsessions, she failed to recognize the extraordinary intertextual dialog De Palma conducted with an important cinematic predecessor. Although other directors have conducted an agon with a fellow director—Chabrol and Hitchcock, Woody Allen and Ingmar Bergman—no director other than De Palma has ever more self-consciously inhabited the style and sensibility of another director and yet managed to create a style so distinctly his own. It's not just all of the stylistic devices that are unique to De Palma's cinema, such as the obsessive use of split screen, that distinguish him from Hitchcock. In every way, De Palma's cinema, even at its most Hitchcockian, comes up with remarkably distinct effects. Yet the connections between the two directors, who share a predilection for the same thriller genre and the same film grammar, are perhaps more salient.

As salutary as Peretz's book is, therefore, I think it errs in failing properly to draw out the connections and exchanges between Hitchcock's and De Palma's oeuvres. This lapse occurs even though Peretz offers an insightful account of De Palma's relationship to Hitchcock and the critical opprobrium it has generated: Hitchcock as "the ideal model," the "real thing," is precisely what De Palma "seems to obstruct from direct view, which these accusing viewers seem to want; it is the real face of Hitchcock, a face De Palma scars and distorts, that they desire to see." In my view, no critic—including Peretz—has yet written incisively on the precise nature of De Palma's intertextually Hitchcockian cinema. While other directors, most notably Chabrol and, to a lesser extent, François Truffaut, have also cultivated their Hitchcockian fascinations, De Palma is not a mere Hitchcock obsessive but a director unique in the cinema in his sustained, intently focused obsession with the nature and potentialities of the experience of cinema itself. Hitchcock is famous for his metatextual cinematic experiments, such as Rope and Rear Window, but De Palma goes a step beyond metatextuality. The only way to understand what De Palma does in his Hitchcock homages is to imagine that De Palma immerses himself within the cinematic body of a Hitchcock film and creates a new cinematic life within the Hitchcockian host body. Quoting Hitchcockian film grammar, De Palma constructs entirely new syntax; extending Hitchcock's faith in pure cinema, De Palma takes Hitchcock's pure cinema to places Hitchcock anticipates but never quite ventures (not that he needed to).

When De Palma remakes Hitchcock, he uses Hitchcock films generally as a kind of collage of symbols, metaphors, and techniques that he can recombine, with those of other directorial styles and with his own idiosyncratic obsessions, to make altogether new meanings. To give a sense of what I mean, in Carrie (1976), De Palma makes one of Stephen King's worst-written yet most suggestive novels an occasion for a vigorous mediation on Hitchcock's cinema that frees Hitchcock's fixations to achieve a radical new vision of both cinema and gender. De Palma recasts Hitchcock's Norman Bates as Carrie White, the excruciatingly shy and awkward—yet secretly and thrillingly powerful—heroine with a living Mrs. Bates for a mother. If Hitchcock's Psycho captures feminine anxiety and tormented sexual confusion in black and white, De Palma's Carrie transmutes those psychosexual tensions into vividly dramatic color, recombining Psycho with Hitchcock's magnificent melodrama Marnie, the scarlet suffusions of which now erupt as the palette of the unleashed fury of Carrie's unshackled id. The shower murder sequence from Psycho represents the annihilation of a woman's body as the destruction of the cinematic image itself; the shower sequence in the early portion of Carrie reassembles Hitchcock's tropes to create a new narrative about female sexuality, conceived not through a threat from the outside but from that within, the undeniable force of nature that erupts in Carrie's first menstrual blood. If this red fluid represents trauma here, in the spellbinding prom sequence it figures female wrath, the explosion of Carrie's no longer pent-up force of will. The sequence in which she annihilates her mother with a telekinetically hurled array of kitchen utensils recombines the Psycho shower murder with the excessive force of surrealistic cinema, culminating in the religious blasphemy of the mother's martyr's orgasmic release.

But for me the deeper problem with Becoming Visionary is that the philosophical framework of Peretz's methodology often threatens to subsume the individualistic potency of De Palma's cinema; tellingly, the Introduction leads with its philosophical agenda rather than its focus on De Palma. One gets the uncomfortable feeling, at times, that De Palma is, while not exactly incidental to the philosophical claims of Peretz's argument, an appropriated vehicle through which Peretz chooses to express them. "De Palma," Peretz writes, is a "philosophical filmmaker in that his cinema involves us in a profound logical investigation of the cinematic ways of producing meaning, or of making sense." Peretz means sense here in a deeply philosophical sense: "De Palma's films call upon us 1) to rethink the major categories of sense that have served, implicitly or explicitly, in all major interpretations of art and film, and 2) to examine the particular significance that the art or medium of film has for the general question of sense."

Peretz's analysis transforms De Palma's deeply corporeal, erotic cinema into philosophical abstraction. In De Palma's depiction of Carrie in the shower—which De Palma, revising Hitchcock, turns into a tableau of sexual metaphors (the phallic shower head spewing water, the steam, the surface of Carrie's skin)—she is a woman in autoerotic plenitude startled into the burdens of gendered identity. Peretz's analysis has a resolute knack for dissolving the sexual specificity of De Palma's cinema into philosophical "rigor": "What Carrie discovers under the shower is precisely that she has a period, that is, that she is a body, and a body as nakedness, that is as something that can bleed and therefore be wounded, a naked body that is not a self-sufficient totality but a vulnerable open surface." But De Palma's fascination with Carrie stems from the fact that hers is a woman's body, not just any, philosophically de-sexed body. What any analysis of De Palma's cinema needs to address is his fascination and conflictual identification with the feminine. If charges of misogyny have been unfairly leveled against De Palma—and I would argue that it is precisely because of his investment in femininity that De Palma has been paradoxically branded a misogynist; of all of the other great New Hollywood directors of the Seventies, De Palma is the only one, other than, perhaps, Robert Altman, who truly attempts to explore feminine identity—any profound investigation of his work must address these issues, the gendered specificity of his cinema. Peretz has little to say on the question of misogyny or genderbending in De Palma's cinema (he almost entirely leaves out Dressed to Kill and Raising Cain, reservoirs of these concerns, from his study). The philosophical focus freezes out the erotic body of De Palma's cinema.

Despite my frustrations on occasion with Peretz's approach, on its own terms his study is penetrating in its brilliance and often daring in its interpretations. Becoming Visionary goes a long way towards establishing De Palma as the great director that he is, even as it reminds one of how much more needs to be said and done—and seen—in this regard.

To buy Becoming Visionary click here

David Greven, an Assistant Professor of English at Connecticut College is the author of the forthcoming Manhood in Hollywood from Bush to Bush (University of Texas Press).

Copyright © 2008 by Cineaste Magazine

Cineaste, Vol. XXXIII, No. 3