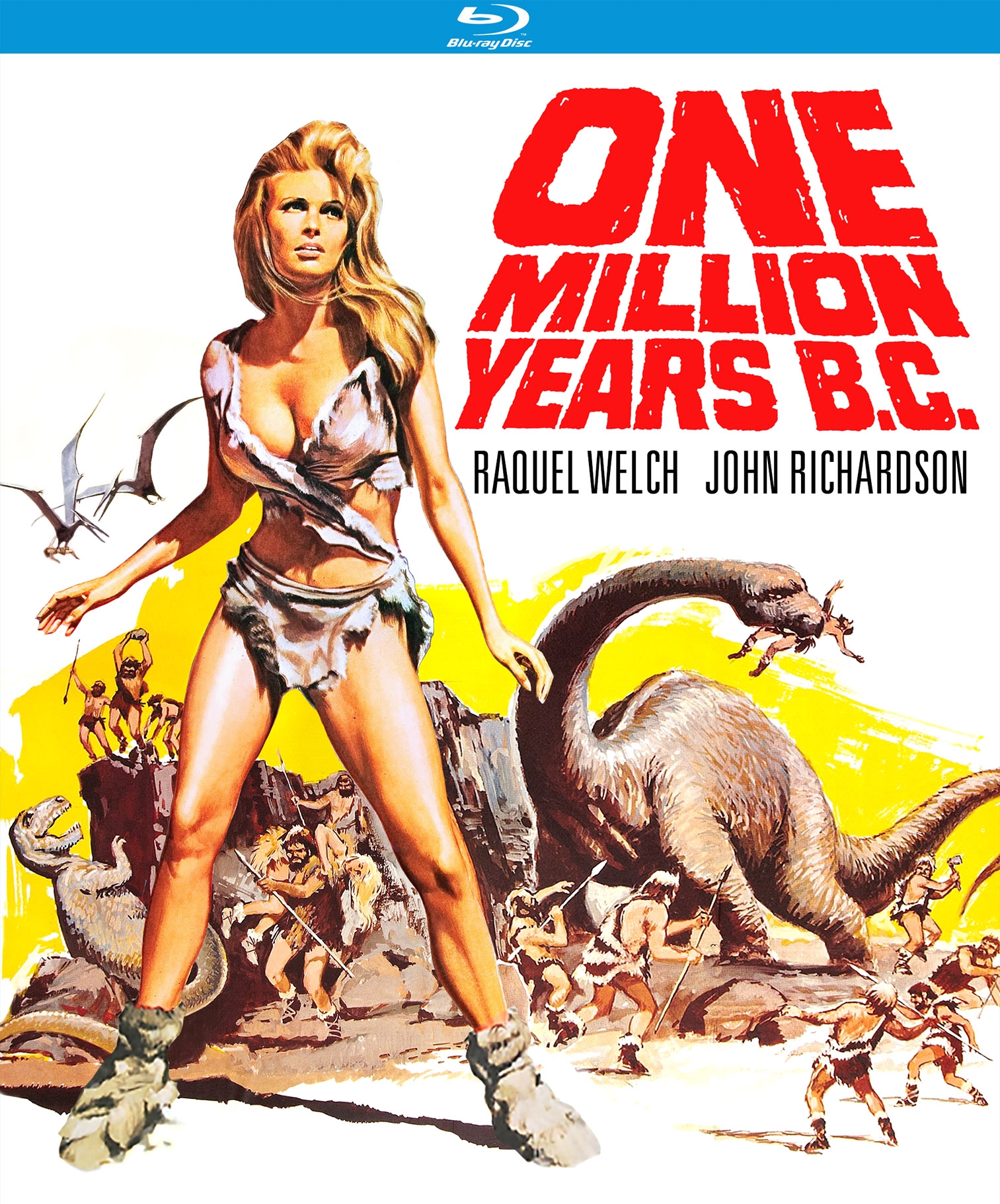

Beauties and the Beasts in Blu-Ray: One Million Years B.C. and When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth (Web Exclusive)

by Robert Cashill

One Million Years B.C.

Produced and written by Michael Carreras; directed by Don Chaffey; cinematography by Wilkie Cooper; edited by Tom Simpson; art direction by Robert Jones; music by Mario Nascimbene; costume design by Carl Toms; visual effects by Ray Harryhausen; special effects by George Blackwell; starring Raquel Welch, John Richardson, Martine Beswick, Percy Herbert, and Robert Brown. Blu-ray, color, 91/100 min.,1966. A Kino Lorber release.

When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth

Produced by Aida Young; written and directed by Val Guest, from a treatment by J.G. Ballard; cinematography by Dick Bush; edited by Peter Curran; art direction by John Blezard; costume design by Carl Toms; visual effects by Jim Danforth; special effects by Alan Bryce, Roger Dicken, and Brian Johnson; starring Victoria Vetri, Robin Hawdon, Patrick Allen, and Drewe Henley. Blu-ray, color, 100min, 1970. A Warner Archive Collection release.

Science tells us that dinosaurs died out sixty-five million years ago, and that humans have been around for only 190,000 years. Telling us differently are the creationists behind Ark Encounter, a $101 million theme park that opened last year in the land that time forgot (that is, the state of Kentucky, which publicly financed some of its construction). Ken Ham, the director of Answers in Genesis, the fundamentalist Christian sect behind the project, claims the Earth is only six thousand years old, and that a centerpiece diorama depicting dinosaurs, humans, and “a race of giants” fighting gladiator-style in an arena is thus true to life.

To say there is considerable reason for skepticism regarding this claim is an understatement. But it is established and incontrovertible fact that dinosaurs and humans did co-exist fifty years ago—on TV’s The Flintstones, and in One Million Years B.C., the big-screen hit that launched twenty-six-year-old Raquel Welch to stardom. (“A marvelous breathing monument to womankind,” raved The New York Times.) Indeed, we’ve been together since about the dawn of movie time, when animator Winsor McKay interacted with his creation, Gertie the Dinosaur, in 1914. The stop-motion alchemy of Willis O’Brien brought us together, as contemporary explorers visited The Lost World (1925) and retrieved King Kong (1933) from prehistory. In 1940, the clock was set back to One Million B.C., as cave people Victor Mature and Carole Landis skirted lizards blown up to dinosaur size in footage recycled for decades in B-movies. “I had to ‘ugh’ my way through that picture,” Mature recalled.

Ray Harryhausen models one of the stars of the show, the Ceratosaurus.

Notwithstanding an Oscar nomination for the film’s effects, dinosaur fans “ughed” their way through the tarted-up reptiles and man-in-costume “suit-a-sauruses” of One Million B.C., which felt regressive after O’Brien’s earlier wonders. 1966’s One Million Years B.C., an attempt by England’s Hammer Films to remake its way out of the Gothic mode of its Dracula and Frankenstein series, corrected that flaw by hiring O’Brien’s protégé, Ray Harryhausen, to create more realistic stop-motion creatures. And it also upped the sex appeal. While Welch called her blue-eyed co-star, John Richardson, a “hunk,” she would be the main attraction this time—indeed, months before the movie opened, publicity photos taken of her on location in the Canary Islands had already caused a major stir.

How alluring is Raquel Welch in the movie? So much so that in The Shawshank Redemption (1994) prisoner Tim Robbins uses a pin-up poster of her to conceal the tunnel he’s carving through a wall, figuring, correctly, that none of the guards would dare disturb it. It was her second feature, after a supporting part in the same year’s Fantastic Voyage. There her male co-stars pull clinging antibodies from her tight-fitting wetsuit, as they travel through an injured scientist’s body in a microbe-sized submersible. “I was in sci-fi hell…did Lana Turner start this way?” she muses in an archival interview on the new Blu-ray of One Million Years B.C. The doeskin bikini-type wear esteemed theater designer Carl Toms created for her was scarcely more comfortable in the cold and wet far from the Canary Islands’s beaches. But no one claws at her, other than a couple of flying pterosaurs. Loana, a member of the Shell People, is her own cavewoman.

One Million Years B.C.: Raquel Welch in the still that launched her career.

Evangelicals disturbed by the pulchritude can take comfort in the storyline, which cribs from the Bible. Tumak (Richardson, who had previously ceded the spotlight to Barbara Steele in Black Sunday, reviewed in Cineaste Vol. XXXVIII, No. 2, and Ursula Andress in Hammer’s remake of She) squabbles with his father Akoba (Robert Brown), the leader of the brutish Rock People. Exiled into the volcano sands beyond their territory, home more to beast than to man, Tumak is rescued by the Shell People, and tended to by Loana. Apart from an occasional attack by an Allosaurus, theirs is a more Edenic existence, with tribespeople who communicate through laughter, tears, and a word or two. (Welch “akitas” and “udalas” her way through the picture.) Tumak’s bestial ways get him kicked out of paradise, but Loana joins him in his perpetual exile. Circumstances oblige them to rejoin the Rock People, who have been taken over by Tumak’s conniving brother, Sakana (Percy Herbert). There Loana must square off against Tumak’s former lover, Nupondi (Martine Beswick), in mortal combat. Yet in victory she refuses to kill Nupondi, as her civilizing influence takes hold. Rocks and Shells unite, warily, to take arms against reptilian agitation and Sakana’s tyranny, with a final earthquake and volcanic eruption clearing the air for peaceful coexistence.

Welch doesn’t appear in the movie until almost the half-hour mark, but the unusual locations, and Mario Nascimbene’s “primeval” score, are compelling in their own right. The movie doesn’t embarrass her, and Loana, who has brains and brawn to go along with her bikini, makes a good case for advanced civilization. There are no dumb blondes among the Shell People. In the U.S. cut of the film in this two-disc set, the one kids like me saw over and over again on WABC’s “4:30 Movie” in New York B.C. (Before Cable), the movie does seem to stereotype the hirsute, dark-haired Rock People as the bad guys. Not so the longer International version, where Tumak and Loana are frightened by a cannibalistic tribe of ape men, and recognize how far they’ve come as humans, and how far they need to go to survive.

While the U.S. cut has nostalgia in its favor, the International version on the second disc is the keeper. Not only does it rescue that key scene, it also has more dinosaur footage, which, incredibly for Harryhausen buffs, was also whittled down. Reunited with Don Chaffey, the director of his legendary Jason and the Argonauts (1963), this was work-for-hire for the animator, but it has splendid passages. The pterosaur attack, which sees Loana lifted into the skies, dropped into a nest for its hungry hatchlings, and fought over by another creature, is a classic sequence, and there’s no way to better a genre staple, a battle between a horned Triceratops and a meat-eating Ceratosaurus, no matter that an epoch or two separated the species in real life. (“Professors care about those things, not audiences,” Harryhausen scoffs in an interview segment.) But the menagerie begins disappointingly, with another actual lizard stomping through the first scene. While appearing to be a homage to One Million B.C., it was intended to be a curtain raiser for Harryhausen’s work later in the film, and he admits to it being a letdown. Budget cuts reduced an epic climactic battle between the tribes and a Brontosaurus to just a twenty-second glimpse of his splendid model early on. Harryhausen’s final exploration of prehistory, the cowboys vs. dinosaurs adventure The Valley of Gwangi (1969), was he felt definitive, and it, too, is now on Blu-ray, making all of his features available in the format.

An Allosaurus confronts the Shell People in One Million Years B.C.

Tumak (John Richardson) and Loana (Raquel Welch).

Kino Lorber’s Blu-ray of One Million Years B.C. includes a typically thorough and engaging commentary by film historian and Video Watchdog publisher Tim Lucas, covering everything from the movie’s links to the James Bond series (Beswick had small roles in From Russia with Love and Thunderball, while Brown, quite expressive as Akoba, succeeded Bernard Lee as M), the birth of the “Raquel Welch genre” after the film became Hammer’s biggest hit, and an intriguing aural resemblance between the final note of Nascimbene’s score and the following year’s Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Besides the fifteen-year-old interviews with Welch and Harryhausen, the disc includes a fun new interview with Beswick (who recalls her off-screen attraction to Richardson, her future husband, and how she and Welch performed their big “catfight” themselves when their stunt doubles proved inadequate) and an animated montage of posters and images, including an arresting one of a crucified Welch. The film’s Biblical allusions don’t go quite that far; fifty years later, however, Loana still manages to “cross” time barriers.

[One Million Years B.C. completists with region-free Blu-ray players—hello!—may also want to obtain StudioCanal’s release of the film, which appeared in advance of Kino Lorber’s. The boxier 1.66:1 aspect ratio differs from the wider 1.85:1 framing of the U.S. transfer—its colors, particularly the exteriors, looked a tad more vibrant on my screen. Besides the Beswick interview, there’s a new sitdown with the ever-stunning Welch, who embroiders her earlier stories with more details, like how her children were fascinated with Harryhausen’s models when they visited his London studio. His fans will appreciate a selection of stills and artwork, and storyboards from the discarded ending.]

Julie Ege in Creatures the World Forgot.

Hammer’s subsequent Prehistoric Women (1967), starring the sultry Beswick but insufficient prehistoric creatures, flopped. The natural order (according to primeval cinema) was restored in the studio’s When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth (1970), which is now on Blu-ray from the Warner Archive. Contrary to the title, the first dinosaur we see, a captive plesiosaur, is burned alive and eaten when it tries to escape, and blondes like Sanna (Victoria Vetri) are having no fun. Another bestial dark-haired tribe is sacrificing her gentler kind to the Sun God, as the planet is rocked by periodic atmospheric disturbances. Adding religious superstition to the mix, the film reworks One Million Years B.C., with Sanna, who flees, the wanderer this time. She is eventually coveted by the manly Tara (Robin Hawdon) after many pitfalls, including her near-consumption by a carnivorous plant and his near-sacrifice to another seagoing plesiosaur. In the film’s cutest scenes, Sanna domesticates an adorable baby “made-up-asaurus,” which, added to her rudimentary numbering system and other charms, seals the deal for the smitten Tara. Both survive to witness an extraordinary event, the one causing the tides to churn, the birth of the moon.

In short, lots of ahistorical, unscientific balderdash for Ken Ham to incorporate into his theme park. I’m not sure he’d appreciate this uncut version of the film, however, which eluded U.S. viewers for decades—Sanna and Tara have a near-nude sex scene, and Sanna bathes topless soon thereafter. [This was news to Warner Bros., which distributed the film on DVD via Best Buy with a G rating, and faced a minor ruckus upon its release. The Blu-ray retains this stronger cut, from a time when a declining Hammer was spicing up its wares with nudity and greater violence, and is now unrated.] The explicit content feels like another patch holding together a turbulent production, written and directed, unhappily, by Val Guest (who got the studio on its feet with the classic sci-fi thriller The Quatermass Xperiment in 1955), from what he called “a sketchy treatment” submitted by none other than that master of dystopian literature, J. G. Ballard. The film’s producer, Aida Young (the highest-ranking woman at Hammer), liked his novel The Drowned World, but few of his concepts made it into the movie, which mistakenly credits him as “J.B.” He and Anthony Burgess, who contributed languages for the more fastidiously accurate Quest for Fire (1981), did what they could to uplift prehistoric cinema.

Stop-motion animator Jim Danforth received his second Oscar nomination for When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth.

Besides the plot elements, When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth also recycles the Canary Islands for locations, the “akitas” and “udalas” for speech, and Nascimbene, whose score is more like his fanfare-heavy efforts for movies like The Vikings (1958). Vetri, Playboy’s Playmate of the Year in 1968, made an in-joke appearance in Rosemary’s Baby that same year, and is appropriately fetching as Sanna. Perhaps in part because she and Guest lacked rapport (he called her a “nitwit”), she doesn’t command the screen with Welch’s confidence, and her career stalled. Vetri recently transitioned from the big screen to the big house, and is currently in prison for the attempted murder of her fourth husband.

The assignment was equally trying for animator Jim Danforth, an Oscar nominee (for George Pal’s 1964 fantasy 7 Faces of Dr. Lao) who came onto the film in Harryhausen’s absence, then fell out with the production, as the front office nixed his Tyrannosaurus for having a “gay stance.” (As if to answer the slight, a burly T-rex’s roars unfurl a banner reading “When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth” in 1993’s Jurassic Park.) Danforth’s work on the accepted menagerie is spectacular, highlighted by some unsettling giant crabs and a charging Chasmosaurus, and his special effects earned Hammer its one and only Oscar nomination. But the movie was draining, and someone threw in blown-up reptile footage from Irwin Allen’s 1960 remake of The Lost World, which Allen recycled again and again for his cut-rate TV shows (Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, etc.)

Hammer’s final film in this vein, 1971’s Creatures the World Forgot, forgot to add any creatures, and vanished. The burlesque of Ringo Starr in Caveman (1981) helped hasten the separation of early man and dinosaurs in movies—and, now that we manufacture them ourselves, in the Jurassic Park movies, we don’t need our ancestors to guide us through lost worlds. Indeed, we don’t need humans at all to add dino drama, something proved by the BBC’s Emmy-winning Walking with Dinosaurs (1999), whose prehistoric animals, observed in CGI-rendered habitats with narration alone as an escort, captivated TV viewers. But the trope persists, recently in Pixar’s The Good Dinosaur (2015), which was rejected by creationists for presenting an alternate reality where humans and dinosaurs mingled. “In fact, according to the Bible’s history, dinosaurs and man were created on the same day,” moaned a representative from Creation Ministries International upon its release. Untrue—but maybe we can all agree that Raquel Welch, a superior example of homo sapiens, came a day later.

Robert Cashill, a member of the Online Film Critics Society, is a Cineaste Editor and the Film Editor of Popdose.

Copyright © 2017 by Cineaste, Inc.

Cineaste, Vol. XLII, No. 3