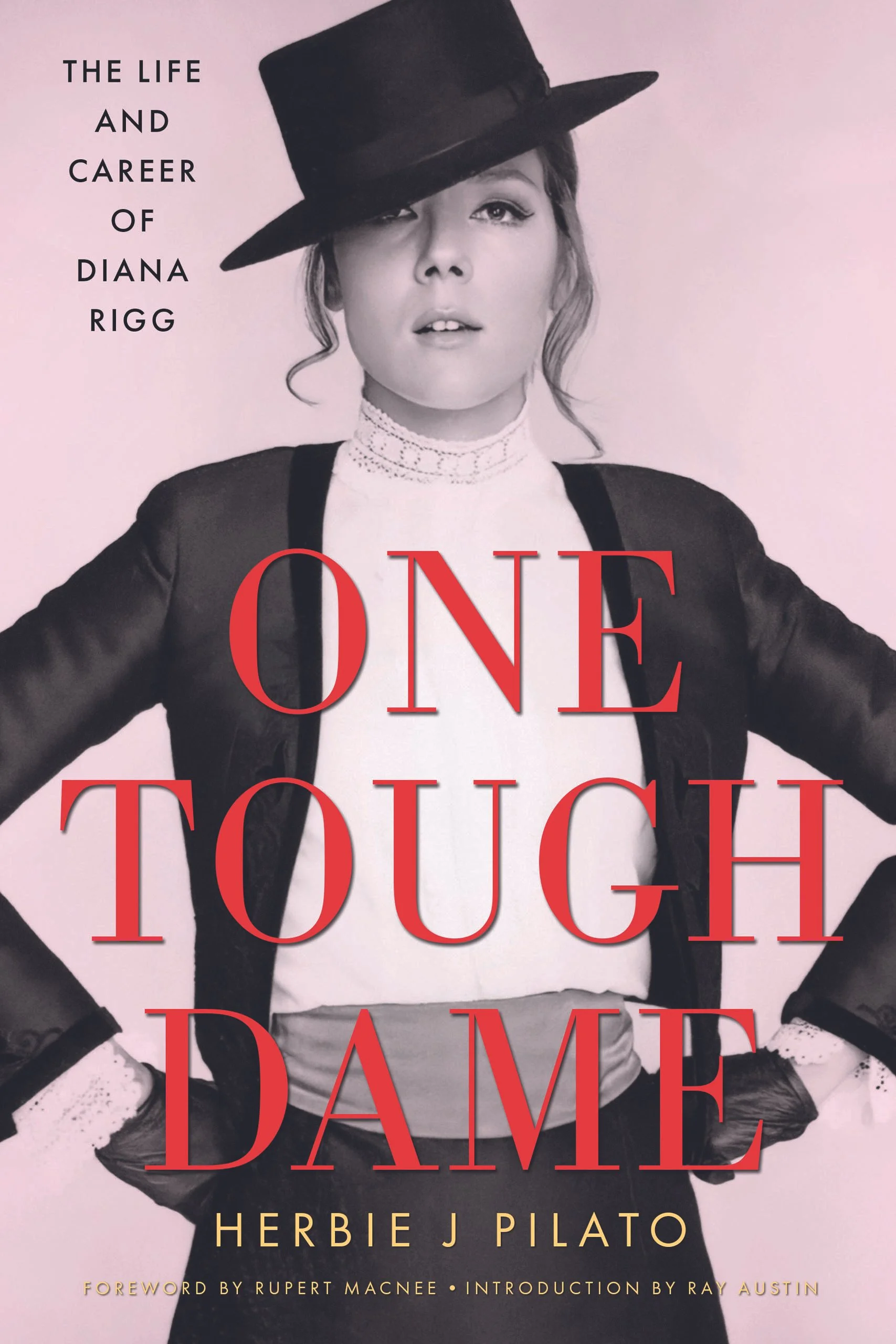

One Tough Dame: The Life and Career of Diana Rigg (Web Exclusive)

by Herbie J. Pilato, with a foreword by Rupert Macnee and an Introduction by Ray Austin. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2024. 217 pp., illus. Hardcover: $35.00, Kindle: $14.91.

Reviewed by Page Laws

She was my idol, and, yes, indeed, I considered her “One Tough Dame.”

I may have had the physical hots for suave Patrick Macnee (Rigg’s co-star in The Avengers from 1965 to 1968) and for David McCallum (over on a different network’s The Man from U.N.C.L.E. series), but I worshipped and longed to emulate the protofeminist attitude, smooth Kung Fu moves, and, above all, the unstoppable smarts and courage of Diana Rigg as Emma Peel. Even as a relatively svelte teenager, I could never have gotten into one of her catsuits. But I could still fantasize from afar and long to be Mrs. Emma Peel, if not a feminist (she balked at that label), at least as “protofeminist” as one could be in her time.

Diana Rigg as Viola, with Sir Toby Belch (Brewster Mason, left) and Sir Andrew Aguecheek (David Warner), as they prepare for their duel in the 1966 Royal Shakespeare Theatre presentation of Twelfth Night.

Now comes a new conjuration of Rigg’s personal magic in the form of One Tough Dame: The Life and Career of Diana Rigg, written by a prolific entertainment industry biographer Herbie J. Pilato, whose other biographical subjects include Elizabeth Montgomery, Mary Tyler Moore, and Sean Connery, among others.

Born in 1960, educated at UCLA, Pilato is skilled in researching his subjects via interviews and research, but he doesn’t really attempt serious criticism or evaluation of Rigg’s work. (In that, this book seems like Kathleen Tracey’s Diana Rigg: The Biography [BenBella Books, 2015], not examined for this review but apparently similar in scope.) Pilato selects two interesting former co-workers of Rigg (or relatives thereof) to write a helpful Foreword and Introduction. The first is by Patrick Macnee’s son Rupert who knew Diana well through his father, and the second is by Rigg’s Kung Fu instructor for The Avengers. Despite Pilato’s lack of any substantial attention to Rigg’s performances, he does prove that he can present a thesis and stick to it.

As Emma Peel in The Avengers, Diana Rigg demonstrated her karate skills, and despite training with stuntmen, she said “I was still black and blue by the end of most days.”

In a publicity portrait for The Avengers, Emma Peel borrows John Stead’s bowler hat and his sword-concealing umbrella.

His main idea here is that Rigg fought hard against being stereotyped as Emma Peel—leaving The Avengers after two seasons when she and it were still alive and (literally) kicking (the bad guys). This was due to her refusal to abandon her Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts training and youthful Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC) experience that made her determined to pursue her theatrical career in a wide array of roles (classic and modern; comic and tragic) in a variety of genres and media. But this also makes her a difficult subject for biographers, especially those relying on fanboy enthusiasm rather than critical close readings.

In this regard, one might question Pilato’s decision to structure the entire book around the Emma Peel experience. Part One, for instance, is entitled “Before [The Avengers]”; Part Two is “During”; Part Three is “After”; and Part Four is “Forever After,” with a focus on her celebrated role in Game of Thrones (2013–17) as Olenna Tyrell.

Rigg had an impressive career on British television, on stage in the West End and on Broadway, and later in both American and British films. But Pilato’s narrative most often merely cites a new role with little more than a mention of the production’s title and Rigg’s co-stars. She portrayed, for example, innumerable roles in Shakespeare productions, mostly on stage but also on screen. She began with the RSC and eventually moved to the National Theatre Company at the Old Vic. She played a daughter to three different megafamous King Lears—Charles Laughton, Paul Scofield, and Laurence Olivier. She performed with many British stars, including John Gielgud. She co-starred with America’s “big dog” actors as well, including Orson Welles, George C. Scott (in 1971’s The Hospital), Vincent Price in Theatre of Blood (1973), Jason Robards and Charlton Heston (the last two in 1970’s Julius Caesar). She also performed in Bertolt Brecht plays—The Caucasian Chalk Circle and Mother Courage and Her Children as well as those by French classicist Molière (The Misanthrope) and modernist Jean Giraudoux (Ondine).

She became briefly famous for marrying James Bond (a miscast George Lazenby in 1969’s On Her Majesty’s Secret Service), but her character, Contessa Teresa di Vicenzo, could not, of course, be allowed to live much past the wedding. Other spy and detective roles for film and television came her way, including Agatha Christie’s Evil Under the Sun (1982) and The Mrs. Bradley Mysteries (1998–2000), among others. She also ranged from lightweight American films such as The Great Muppet Caper (1981), an ill-fated NBC sitcom called Diana (1973-74) and more substantial stage performances, such as West End and Broadway productions of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1973–74).

Rigg appears as Regan, the treacherous daughter of King Lear (Laurence Olivier), in a 1983 televised production of a Royal Shakespeare Company touring production of King Lear.

Amidst this tidal ebb and flow of shows and films, we get brief looks at Rigg’s love life, including her two husbands: artist Menachem Gueffen (married from 1973 to 1976) and Archie Stirling (married in 1980 and divorced in 1990). We also finally meet Rigg’s fellow actor/daughter Rachel Stirling. In 1988, Rigg was named “Commander of the Order of the British Empire,” for her varied acting career. Six years later, in 1994, she was made a “Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire.” In addition to her acting career, Rigg edited an anthology of notoriously bad theatrical reviews called No Turn Unstoned (Doubleday, 1983).

Though Pilato sticks to his thesis idea of Rigg’s having been marked but not limited by her Avengers past, he is less skilled in ordering the many events of Rigg’s life, giving us relatively little of her childhood and youth in the U.K. and India, and sometimes discussing events out of order or repeating himself. We’re told, for example on page 67, about Rigg’s daughter being an actress, before we’ve even be told she has a daughter. Among other questionable aspects of Pilato’s biography, we surely do not need to know the exact worth of Diana Rigg’s estate at her death. That seems both invasive and tacky. We can likewise do without Pilato’s somewhat demeaning armchair psychoanalysis about why Rigg smoked so obsessively (she died of lung cancer in 2020). “Had Diana not smoked so obsessively, maybe her skin may have retained slightly more elasticity, her teeth might have remained a little whiter; and maybe she possibly would have lived a trifle longer. One will never know.” Ouch! The observation seems needlessly judgmental. We also learn, in true tabloid fashion, that Rigg experimented briefly with drugs but apparently moved on quickly from that potentially deadly habit.

Since Pilato played a significant role in founding The Classic TV Preservation Society (CTVPS), the real fun of this book is rifling through the numerous photos of Rigg in various film and stage performances, along with her co-stars, with nearly every photo in the book credited to this collection.

Rigg as Lady Macbeth with Anthony Hopkins in the title role in a 1972 production of the Shakespeare play.

All her roles were not star-quality, and she always refused to be labeled a bra-burning feminist. But she was, sort of. She insisted, for example, from the Emma Peel era onward, that women should be equitably paid. And then, late in her life, she took the role of Mrs. Pumphrey, owner of Tricky-Woo, the upstaging Pekinese canine, in All Creatures Great and Small (2019, dying after the first season had been completed). Her masterful performance eclipsed the fussy pup. It was a hearkening back to many a Masterpiece or Mystery show in which she swept all before her. During her life, Rigg conquered Broadway and her own British Isles. She was a master of her craft, and a cracking good feminist, in spite of herself.

Page Laws, Professor of English Emerita and Founding Dean of the R. J. Nusbaum Honors College at Norfolk State University, is corresponding theater and opera critic for The Virginian-Pilot newspaper.

Copyright © 2025 by Cineaste, Inc.

Cineaste, Vol. L, No. 3