Breathless

Reviewed by Armond White

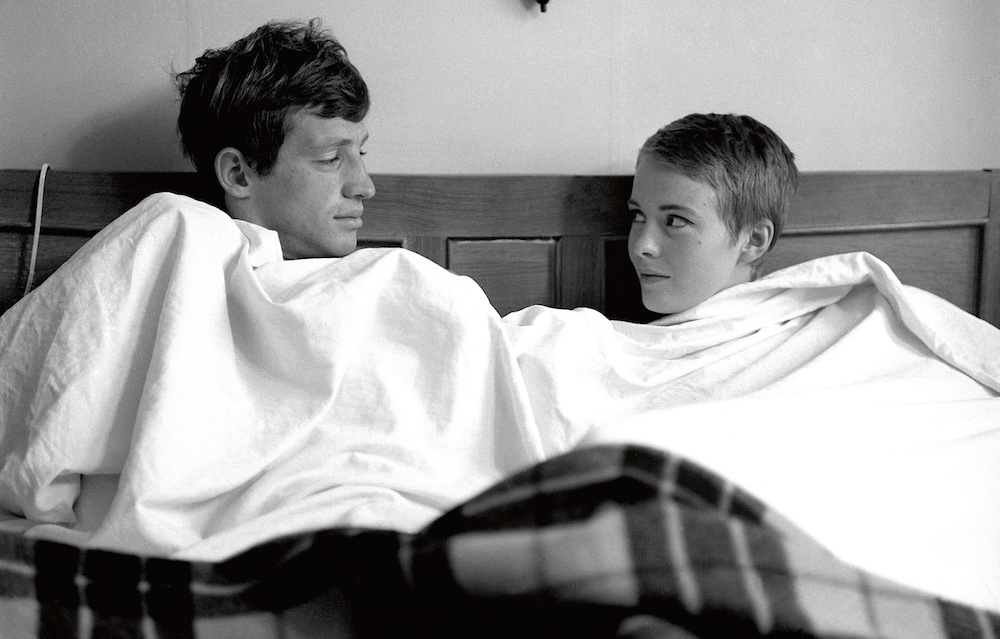

Jean Seberg and Jean-Paul Belmondo.

Directed by Jean-Luc Godard; screenplay by Godard, based on an original treatment by François Truffaut; cinematography by Raoul Coutard; edited by Cecile Decugis; music by Martial Solal; starring Jean-Paul Belmondo, Jean Seberg and Daniel Boulanger. DVD, B&W, 90 mins., French dialog with optional English subtitles, 1960.

In a Seventies reassessment of Jean-Luc Godard's 1959 debut feature, critic Colin L. Westerbeck memorably proclaimed "Breathless exists! Breathless exists so that the Siegfried Kracauers of the world can hold their breath. Breathless exists!" He was celebrating a movie that employed cinematic theory as a practical, elating fact. All imaginable advances that came into popular culture following the appearance of Breathless—when commercial cinema and television imitated and trivialized the formal inventions of Sixties European art cinema (such as Godard's casually innovative use of the jump cut)—are facts that we now take for granted.

A certain kind of nonchalance has come from living with Breathless almost fifty years, and watching it in poor prints, faint VHS copies, squished TV broadcasts. The excitement of discovery is almost gone, meaning it's time for rediscovery. First-time viewers might yet find Godard's rigorous technique a challenge—perhaps even intimidating given how the once-novel jump cut, the hand-held camera, on-location shooting, and natural lighting have now become routine and meaningless parts of visual media vocabulary. But what never ceased to be compelling about Breathless is the tragic love story between Parisian bum Michel Poiccard (Jean-Paul Belmondo) and American adventuress Patricia Franchini (Jean Seberg). Their mismatch might be the most revolutionary aspect of Breathless, revealing that Godard's technical experimentation was integral to modernizing a timeless romantic archetype.

The clash of European tradition and American newness are organic to Michel and Patricia's chemistry. Their sexual allure (and Belmondo and Seberg remain one of the most delectable male-female pairings in movie history) gives a sparkling patina to the cultural-political circumstance of Franco-American relations. Breathess scholars have frequently commented on the notoriously censored edit where Michel skirt-chasing Patricia is matched to a shot of a De Gaulle parade—implying French politicians scampering after American policy—but this merely touches upon an obvious political irreverence. It is the femme-fatale plot of Breathless that provides a more powerfully personal sense of European infatuation with Yankee style and supremacy.

Fact is, the poignancy of Michel's crush turning into a crushing love with the uncaring, career-driven American girl creates a fable about the transitory innocence of post-WWII youth. Godard's depiction of Michel and Patricia's mutual love/hate was either prescient or the realization of an eternal cultural condition.

In this classic broken-hearted love story. Michel represents the culture that American power recently liberated being cruelly paid back by the next ahistorical generation. Thus, it expresses both romantic yearning and political severity—timeless human circumstances. Neither Michel nor Patricia are political animals, but they are barometers of attitudes—the real-life politics of daily habits (his restless sexuality, her seemingly complacent sense of power); survival (his petty theft, her careerism) and opportunism (his stumbling upon death in the mechanical murder of a motorcycle cop, her resigned attitude toward betrayal and spiritual death).

Though rarely discussed as either a love story or a political film, Breathless maintains fascination because it is equally both. Godard's political-romantic ambivalence—toward women, toward America (Hollywood) —locates a crucial and basic complexity about what has been called the American century. That doubled feeling, the Michel-Patricia love-hate paradox, has been the subject of several, even epochal films—from Vincente Minnelli's 1951 An American in Paris to Bernardo Bertolucci's 1972 Last Tango in Paris. Those signposts contain the reverse of Godard's story; the protagonists' positions are altered to American male supplicant and French female idol.

What Godard accomplished through this switch of Minnelli's prototype was a response to Hollywood narrative that spoke back to American mythology. Michel's Bogart-fancy reveals a debt to America that Patricia cruelly collects; as drama it is a psychosexual expression of the European left's view of American imperialism. By the time Bertolucci responded to Godard's modernist vision of cultural and political relations, the male-female antagonism was switched back to the Minnelli model, yet is suffused with a European sense of regret (Brando's American supplicant doesn't reference Bogart but the tragic figures of French poetic realism like Jean Gabin in Port of Shadows and Italian neorealism like Massimo Girotti in Ossessione).

To look at Breathless as an extension of the film noir and gangster movie, based primarily on Godard's stated dedication of it to Monogram Pictures places too much of a limit on all that the film evokes. Its politics run deeper than just a crime story; despite the plot's cop-chase framework, the story moves into more personal-political realm. Godard deepens and elevates his protagonists into figures with the rich psychological compulsions of A-level melodramas like those of Minnelli, Nicholas Ray, and Otto Preminger. (The Preminger connection is made undeniable by Godard's implication of Jean Seberg.)

As the United States' global image currently endures a new era of anti-American sentiment, Patricia's alarming blank expression of innocence at the end of Breathless ("Déguelasse ? I don't know what that means!") seems more resonant than ever. It is more than simply critical of American sexual, romantic, military, political, and economic might; the final image of Patricia also admits enthrallment with that very same irresistible monster. After all, Godard's choice of a career in filmmaking (perhaps the most bourgeois of all artistic pursuits) has to entail a certain degree of guilt for a politically conscious intellectual.

In this sense Michel and Patricia's love story represents innocence in the face of guilt. That's what propels Breathless in the imaginative life of every new generation of college-student film lovers. Although the cinematic canon has shifted in recent years away from Hollywood-based and Eurocentric cataloging, there has been no new film that expresses political and cultural ambivalence as ingeniously as Breathless does.

The legend of Godard's Breathless as the most radical expression of the French New Wave, catapulting the Nouvelle Vague into the vanguard of both cinematic experimentation and popular appeal is revived with its new, enhanced DVD version. For all that the film can now be seen to contain (a love story, a political allegory, a cultural-diplomatic examination, a revolution in film esthetics), its significance is more vibrant than ever. (Best among the DVD extras in Criterion's sharp new release are Godard's early, rarely seen shortCharlotte et son Jules starring Belmondo, a 1959 interview with Jean Seberg, and two interviews with cinematographer Raoul Coutard and assistant director Pierre Rissient that recall the technical risks of the film's production; the use of new techniques and radical attitudes toward filmmaking that should be of particular interest to the current rise in faster, more personal digital-video filmmaking.)

Godard turned theory into practice and romance into politics so successfully that Breathless' central position in film culture and its popularity among serious film-watchers has never receded. Movie history and cultural politics vibrate throughout Breathless. It exists indeed.

Armond White is film critic for The New York Press and author of The Resistance: Ten Years of Pop Culture that Shocked the World and coauthor of Rebel for the Hell of It: The Life of Tupac Shakur.

Copyright © 2007 by Cineaste Magazine

Cineaste, Vol. XXXIII, No. 1