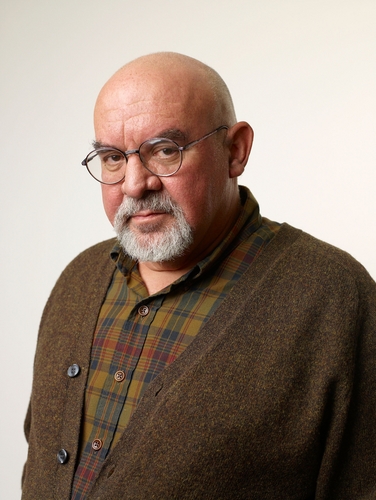

Things No One Likes to Talk About: An Interview with Stuart Gordon

by James Morgart

Director-writer-producer Stuart Gordon burst onto the horror scene with 1985’s Re-Animator, an adaptation of an H.P. Lovecraft short story, one of the great mad-scientist films, and a refreshing change of pace after the decade’s run of slasher movies. Spiced with quirky humor, kinky sex, and showers of body parts, Re-Animator found a fan in Pauline Kael, who rhapsodized about the film in The New Yorker. Gordon applied the same mixture to a second Lovecraft adaptation, From Beyond (1986). Witty and sophisticated without shortchanging on gore or lasciviousness, the two movies inaugurated a career in fantastic cinema that has encompassed a fractured fairy-tale (1987’s Dolls), a science-fiction adventure about giant robots (1990’s Robot Jox, made for a fraction-of-a-fraction of the budget of the Transformers movies), and Edgar Allan Poe adaptations (including 1991’s The Pit and the Pendulum).

When Showtime rounded up filmmakers for its Masters of Horror series, it was only natural that it called on Gordon, who contributed a Lovecraft story for its first season (“Dreams in the Witch-House,” 2005), a Poe for its second (“The Black Cat,” 2007), and a third for Fear Itself, the series’ continuation on NBC (2008’s “Eater”). By then, Gordon’s films had added politics to their witches’ brew of ingredients. Cowritten by noted science-fiction author Joe Haldeman (The Forever War), Robot Jox takes place in a future where war is outlawed, and the two super nations that make up the world duke it out for resources with robots that fight gladiator style. In the U.S. of 1993’s Fortress, a one-child-per-family limit is strictly enforced; a couple that has broken the rule by conceiving a second after their first has died is imprisoned in a futuristic complex laden with nasty mind control and torture devices, including the dreaded “intestinators.”

2007’s Stuck, a torn-from-the-headlines shocker, is based on a notorious 2001 crime. A hit-and-run incident leaves Tom (Stephen Rea), a homeless man, trapped in the windshield of a car driven by Brandi (Mena Suvari), a retirement home worker. Brandi promises help once she parks the car in her garage, then reconsiders, triggering a cat-and-mouse game between the protagonists. Gordon also directed the 2005 film version of one of David Mamet’s bleakest and most horrific plays, 1982’s Edmond. Protagonist William H. Macy walks out on his comfortable life and into an ugly urban underbelly rife with racist taunts, casual brutality, and murder.

Gordon and Mamet came up together in the Chicago theater scene. While a student at the University of Wisconsin, Gordon was one of the 10,000 who participated in the protests against the 1968 Democratic National Convention in the city. He shaped the experience into a controversial student production of Peter Pan. The play’s content was largely unchanged, but Pan and the Lost Boys were recast as hippies, Wendy and her brothers as straitlaced suburban kids, and Captain Hook and his band of pirates as, of course, Mayor Richard J. Daley and the Chicago police. Tinker Bell’s fairy dust became LSD. But what really created controversy was the trip to Neverland in which a psychedelic light show was projected on the bodies of seven naked dancers.

Though a hit, Peter Pan caused Gordon and his wife (Carolyn Purdy-Gordon, one of the nude dancers, and a frequent costar in his films) to be arrested for obscenity. Gordon recalls that the district attorney could press charges only if someone from the community issued a complaint. Unfortunately for the prosecutor, the only person to come forward turned out to be a convicted child molester. (Gordon plans to turn this story into a film, ‘68.)

All charges were withdrawn and Gordon and Purdy-Gordon moved to Chicago in 1970, where they formed the groundbreaking Organic Theater Company. The Organic made a name for itself with adaptations of Animal Farm and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and original productions like the three-part sci-fi epic Warp!, Bleacher Bums, E/R Emergency Room, and the world premiere of Mamet’s Sexual Perversity in Chicago. The company launched the careers of actors such as Joe Mantegna, Dennis Franz, Meshach Taylor and John Cameron Mitchell.

Though his career has had brushes with Disney (notably the story for the 1989 hit Honey, I Shrunk the Kids and the 1998 Ray Bradbury adaptation The Wonderful Ice Cream Suit) Gordon maintains his independence. He was interviewed for Cineaste by aspiring filmmaker, James Morgart, who has made his own horror movie, Won Ton Baby!—Robert Cashill

****

Cineaste: Of Re-Animator, Pauline Kael wrote, “This horror film about a medical student with a fluorescent greenish-yellow serum that restores the dead to hideous, unpredictable activity is close to being a silly ghoulie classic—the bloodier it gets, the funnier it is. It’s like pop Buñuel; the jokes hit you in a subterranean comic zone that the surrealists’ pranks sometimes reached, but without the surrealists’ self-consciousness (and art-consciousness)... Barbara Crampton is the dean's creamy-pink daughter (who’s at her loveliest when she's being defiled)." What was your reaction to this review, which, along with other rave reviews, put the film on the map?

Stuart Gordon: I was amazed, because I made a film that I thought the critics would hate. In a way, the fact that I took that approach is one of the reasons why I think it worked out as well as it did. I wasn’t worrying about the critics and I really didn’t expect the critical success, because what I had set out to do was: first, to make a film that I wanted to make; and second, to make a film that I thought the fans wanted to see. I think it was Roger Ebert who discovered the movie at Cannes and his review wound up creating buzz for the film that resulted in other critics reviewing the film, so I was pleasantly surprised at the responses that the film was getting. I have always been an avid reader of Pauline Kael, so when I read that she liked the movie, I just loved what she had to say, especially about Barbara Crampton’s character.

Cineaste: Do you find that, when it comes to horror, the fans tend to drive the industry more than other genres?

Gordon: The fans are definitely the most loyal of any genre. The horror fans are just incredible. The thing I keep discovering is that, first of all, they read everything. They’re incredibly well-read, so I’ve had great discussions with them on Poe or Lovecraft. And secondly, they don’t necessarily like everything. They’re extremely discriminating. I think that when it comes to horror fans, they really do try to see and know everything within the genre.

Cineaste: It seems that almost all of your films deal with ambition, power, and greed, from Honey, I Shrunk the Kids, where ambition both literally and metaphorically shrinks a scientist’s children, to Re-Animator, where it leads to horrific scientific advances. Are these statements about ambition’s negative effects intentional?

Gordon: I think these films are about dreams, and how incredible dreams can be. And the horror about dreams is that you have to be careful, because sometimes they can wind up becoming nightmares. Basically, at their root, they follow that old adage you’ve got to be careful what you wish for.

Cineaste: What do you think of the phrase “torture porn”?

Gordon: I hate it. First of all, there’s the phrase “porn” being thrown in there and there’s always been that stigma of horror being likened to porn. Secondly, torture is something that’s existed in drama since the very beginning. Shakespeare uses it effectively in King Lear. Honestly, I think whoever uses this phrase just doesn’t like horror very much.

Cineaste: Given their explicit violence, could films like The Pit and the Pendulum and Dagon (a 2001 Lovecraft film) be considered “torture porn”, though they're derived from classical sources?

Gordon: There’s torture in them. But I think horror reflects society, and the fact that for decades we’ve had horror films that have torture in them reflects the fact that for years we’ve had a government that endorses torture. Most recently, torture has been on the front page of the newspapers almost every day, and you’ve got people like Dick Cheney defending torture as something that’s necessary for our national security. So of course you’re going to see it reflected in art.

Cineaste: The films mentioned in reference to torture porn are films like Saw or Hostel, which came out just after details about Abu Ghraib were starting to surface in the press. Does the backlash against a film like Hostel, where humans are commodities, or its director, Eli Roth, come from torture just being too stark of a reality for some people to face?

Gordon: The thing about horror is that it deals with issues that we don’t really want to talk about—starting with the most basic idea, which is death. All horror films deal with death, which is a topic that most people don’t usually discuss. To have the ability to discuss or explore things that society wants to avoid is what makes the horror industry a very great and powerful thing.

Cineaste: Do you find the trend toward remaking horror films of the Seventies and Eighties derivative or inspired in its own way?

Gordon: I think it’s pointless. I don’t like these movies at all. I think when the movie was made, the filmmaker had something to say. When a studio goes out and hires some music video director to remake a film, it’s largely a commercial enterprise.

Cineaste: If you or someone else were planning to rework your older films, what might you do differently?

Gordon: What I’d do differently is that I wouldn’t rework any of my older films. And I’m not that big into sequels. I think that once you’ve done something, you should go on to something else. Unless, after the first film, you feel that there’s still more to say about the subject, which sometimes can happen. I was planning to make House of Re-Animator, but we missed our chance for the film to be relevant as it was to be centered on the Bush Administration. So, in a way, I’m kind of delighted that I don’t have to make it.

Cineaste: How has the marketplace changed for your films?

Gordon: I’m just lucky that people keep watching them. So at the end of the day, it’s really a matter of whether or not you’re proud of your work and the projects you’ve put forth.

Cineaste: What does it mean to be considered a “Master of Horror”?

Gordon: Well, you know, that term started out as a bit of a joke. It came from a documentary being made that was called Masters of Horror and they were interviewing all of us for it. It was [producer-writer-director] Mick Garris who realized that none of us were getting to meet one another as we were being interviewed separately and invited us all to dinner together. So that label “Masters of Horror” was basically born out of that first dinner. Here we were, sitting at this big table at a restaurant, and at a table near us they brought a cake for someone celebrating their birthday. Guillermo del Toro got all of us to stand up and sing “Happy Birthday.” And it ended with him saying, “The Masters of Horror wish you a happy birthday.” It was really fantastic. Then we started meeting every couple of months, and eventually Mick got the idea to do the series so we could all work together.

Cineaste: Edmond was an unusual choice to bring to the screen. How did you and David Mamet collaborate on the adaptation?

Gordon: It was something we had been talking about for years. In fact, I think he had written the screenplay shortly after he had written the play back in the Eighties. When it came to actually make the movie, we worked closely with one another, but the film actually wound up staying fairly close to the original, as it was quite brilliant.

Cineaste: What about the play attracted you?

Gordon: Again I think it’s tackling something that people really don’t want to talk about. The topic being, of course, racism, which is always a difficult one to broach. And the film addresses the idea that everyone is racist, which is something that people don’t want to admit, but it’s true. It’s just a part of the human condition. All you have to do is get into a bad traffic situation and you’ll find yourself saying things that you never would’ve expected could come out of your mouth.

Cineaste: Edmond and Stuck show horror erupting in everyday surroundings. Is there such a thing as “normal life”? Are we all fated to become monsters?

Gordon: I don’t think there’s such a thing as normal. [Laughs] I think that’s something that everyone likes to be. I think everyone has monsters within them and are in one way or another trying to contain them. And a lot of my movies are about monsters, but they’re not about fighting monsters, they’re about being one.

Cineaste: What drew you to the fact-based story of Stuck?

Gordon: It was about an ordinary person, this caregiver of senior citizens, who becomes a monster. How did that happen? After reading about it in the newspaper, I just couldn’t stop thinking about it. I'm influenced by both film and theater, but what I try to be most influenced by is real life. I really think that it's an artist's job to take life and put it into an artistic framework.

Cineaste: Why did you alter the race of the main character, Brandi?

Gordon: My intention was to make it unclear what the race of the main character was. In fact, the character was named after someone I knew who was a light-skinned black girl with green eyes. And so, with her character, there is that element of, “Is she a black girl or is she a white girl who is maybe a black wannabe?”

Cineaste: Edmond and Stuck present a harsh portrait of race. Does the election of President Obama inspire hope or deepen the fissures?

Gordon: I think it’s a great thing, an amazing thing. In fact, I think it’s the only good thing that came out of the Bush Administration. Because it never would’ve happened if things hadn’t gotten as fucked up as they did. But I don’t think his election is going to stop racism. People will always have that irrational fear and that’s not going to go away.

Cineaste: Those fears are surfacing now.

Gordon: I grew up in Chicago and while I was there, Martin Luther King, Jr. decided to march in the streets. And Mayor Daley said, “Well, this is Chicago, there isn’t any racism here”; King’s response was, “Then there shouldn’t be a problem, should there?” But, of course, there wound up being a huge problem as the protesters had stones and bricks and objects hurled at them by my neighbors as they marched. People who didn’t think there was racism in their city found out that, when confronted with the issue, there was a ton of racism within the city. I think it’s better to get it out there and to discuss it than to keep it bottled up and behind closed doors.

Cineaste: I’ve seen photos of you online out at the picket lines during the Writers Guild of America strike. Do you consider yourself an activist?

Gordon: Absolutely. I think I did a lot more back then than I do now. The writers’ strike was the first time I was out on the picket lines in years and years. But I do consider myself an activist.

Cineaste: How does your background in theater and politics of the Sixties inform your work?

Gordon: I think the Sixties were a time of us realizing for the first time that all art is political. We had a lot of turmoil going on around us and we were constantly reacting to that in our work. It’s just something that’s been part of my art ever since. That is, anything I'm going to do is going to be political in one way or another.

Cineaste: On the drawing board is ‘68.

Gordon: I’m hoping to get that made, but it might be a bit of a challenge as it’s the first time I’ll be making a love story. My wife and I are part of the story, so it’ll involve how we met and fell in love. But it’ll also involve our being tear-gassed at the convention and our arrest following the adaptation of the Peter Pan play.

Cineaste: So it’ll extend the politics of your work?

Gordon: Absolutely. It’ll be focused on the politics of the Sixties, as I really don’t think there’s ever been a great film about the Sixties that’s been able to capture the turmoil and turbulence of the time.

Cineaste: Edmond says, “Behind every fear is a wish.” Do you agree?

Gordon: I think your fears change throughout your life. But, I think that you always wish the best for the people you love, so there’s always that fear that something bad will happen to them. There’s this whole subgenre of horror films emerging right now about children who are killing their parents. And I think that’s one of the new fears now, that we’re becoming afraid of our own children. I don’t know why that is. Maybe it’s a Boomer thing, that my generation is now getting old and should just get out of the way of the younger generations. Maybe it’s technology that’s become a dividing line between us and our own children. “Oh, Dad is too dumb to figure out e-mail.”

James Morgart is a graduate student in Penn State University’s English Program, where his area of study is American Gothic Literature and Film. His writings have appeared in popular horror media outlets such as Fangoria, HorrorNews.net and Gorezone Magazine. His own first feature film, a horror-comedy titled Won Ton Baby!, is currently in postproduction.

Copyright © 2009 by Cineaste Magazine

Cineaste, Vol. XXXV, No. 1