Trumbo on Trumbo: An Interview with Christopher Trumbo (Web Exclusive)

by David Sterritt

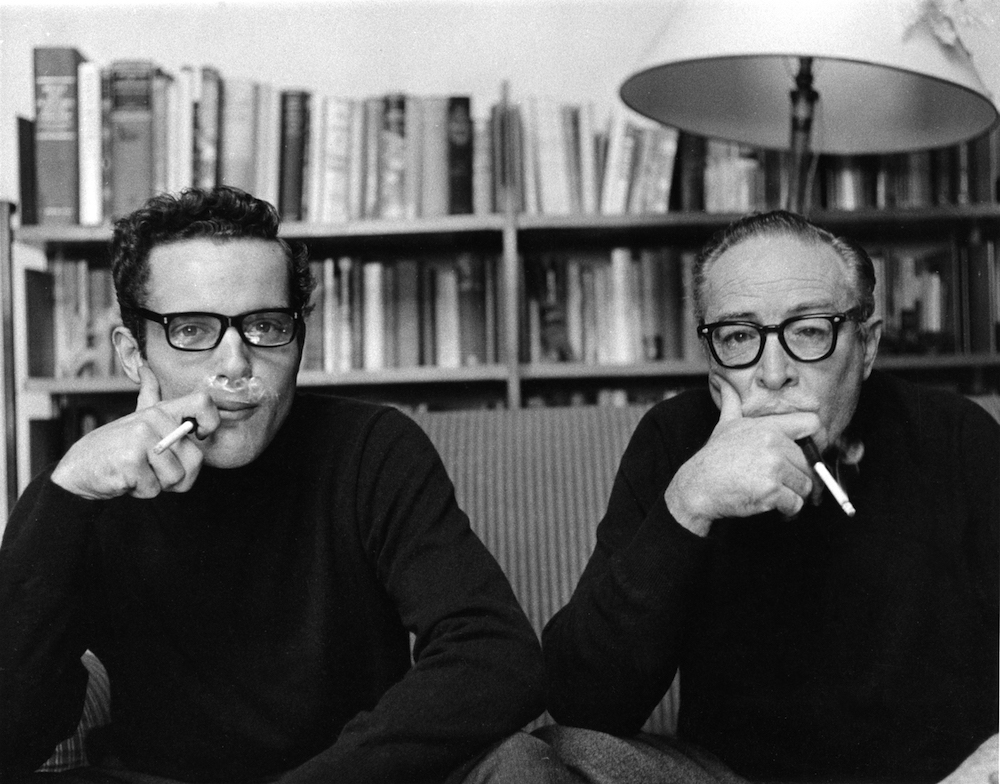

Christopher Trumbo (left) and his father, Dalton Trumbo (right)

Christopher Trumbo, born in Los Angeles in 1940, observed Dalton Trumbo’s blacklist experiences as a child—in their home and visiting him in jail—and explored them through conversations and correspondence until his father’s death in 1976. They also worked together at times; in 1971 Christopher was assistant director of Johnny Got His Gun, the only film Dalton Trumbo directed, and in 1973 he wrote (uncredited) the Devil’s Island sequence of Papillon when illness forced his father to withdraw. I talked with him about Trumbo at his home in Ojai, California.

Cineaste: What prompted you to write the play Trumbo and then the documentary film?

Christopher Trumbo: I did it basically because the history of the blacklist has been misunderstood in all kinds of ways. People often think it was part of the [Senator Joseph] McCarthy era, but this was before that time. Also, people don’t realize that the blacklist had different periods within it, times when it was easier to get work and when it was more difficult.

Cineaste: There was a lot of murkiness and misunderstanding even at the time, and even among those involved.

Trumbo: At first no one really knew what the blacklist was, including people who were blacklisted. After eleven people testified—the eleventh was [Bertolt] Brecht, who went straight back to Europe the next day—the [HUAC] hearings were shut down because the press was split about the situation and the law reviews were saying the [Hollywood] Ten had a good case, so the committee didn’t know what its legal position was going to be. Meanwhile the studios were waiting to see what would happen, still hiring people but maybe for less money. When the Ten were sentenced, the committee understood that it had a lot of power, and so did the Hollywood right wing. So the committee reopened for business, and the people who were called were in a whole different situation because they knew what can happen if you don’t cooperate.

Cineaste: Do you agree with the view that HUAC picked on Hollywood because of the publicity it would bring?

Trumbo: Sure, the publicity value of Hollywood was huge. The images of actors and actresses were carefully managed and presented as products, and they were closely associated with studios, which also had personalities of their own. Of course Hollywood is still an industry, but at that time it was a much more closely held industry.

Cineaste: HUAC and the blacklist didn’t arise out of nowhere. How far back do its roots go?

Trumbo: It was all such a bizarre occurrence, but it’s actually part and parcel of political repression in this country, which begins much, much earlier—the Alien and Sedition Acts [of 1798], President Wilson throwing people who disagreed with him during World War I into jail… it’s a continuing process. You don’t expect something like the blacklist, but suddenly there it is, and you say, “How could they do this?”!

Cineaste: Your father’s letters show that he often thought of being a novelist or playwright instead of a screenwriter. Why was he so determined to get back into movies when he was released from jail and blacklisted?

Trumbo: One problem was earning a living. The second was, if you abandon the industry, how do you convince it, or the Establishment in general, that they can’t do these things? His idea was that if enough people on the blacklist were able to write enough, they could undermine the system, because you’d create a black market that would devalue the regular market. So he wrote a lot, and when rumors started, he refused to either confirm or deny that he was writing a picture. That way he managed to get [his name] associated with the good pictures, and not with the bad ones, which pissed off writers, and the Writers Guild too! In those days, Hollywood was a smaller community, and everyone worked at a studio. So the blacklist destroyed a great many friendships and [badly hurt] the collegial atmosphere among writers. And it became a model for what government can get away with [regarding] anyone whose politics could be considered suspect. That’s what McCarthyism is. And then you have people deciding to avoid these sorts of situations by not speaking their minds at all.

Cineaste: One last question. Are you now, or have you ever been, a member of the Communist Party?

Trumbo: [Laughing] It never occurred to me to join! I always wondered how communism could actually work—how are they going to do those things they talk about?

Cineaste: Some say it’s never really been tried.

Trumbo: That’s a good argument. But you can say the same thing about democracy!

To buy Trumbo click here.

David Sterritt, Chairman of the National Society of Film Critics, writes about movies for Tikkun. The Trumbo DVD is reviewed by Sterritt in the Winter 2009 issue of Cineaste.

Copyright © 2009 by Cineaste Magazine

Cineaste, Vol. XXXV, No. 1