Noriaki Tsuchimoto's Living Records (Web Exclusive)

by Aaron Cutler

Perhaps Tsuchimoto's best known film is Minamata: The Victims and Their World (1971), one of 15 documentaries he eventually made about mercury poisoning in Minamata

On the Road: A Document, DVD, B&W, 54 min., 1963. More information at http://www.zakkafilms.com/film/on-the-road-a-document/.

Minamata: The Victims and Their World, DVD, B&W, 120 min., 1971. More information at http://www.zakkafilms.com/film/minamata-the-victims-and-their-world/.

The Shiranui Sea—Minamata Series Part II, DVD, color, 150 min., 1975. More information at http://www.zakkafilms.com/film/the-shiranui-sea-minamata-series-part-2/.

Traces: The Kabul Museum 1988, DVD, color, 32 min., 2003. More information at http://www.zakkafilms.com/film/traces-the-kabul-museum-1988/.

Another Afghanistan: Kabul Diary 1985, DVD, color, 42 min., 2003. More information at http://www.zakkafilms.com/film/another-afghanistan-kabul-diary-1985/.

All titles distributed by Zakka Films, http://www.zakkafilms.com/.

“I make films so that anyone watching them can understand,” the Japanese director Noriaki Tsuchimoto once said. As several recent DVD releases of Tsuchimoto’s work attest, he did so by shaping each one of his documentary films in tandem with the lives of his subjects. The five Tsuchimoto films released to date by the Japan-centric boutique label Zakka Films, including this year’s release of The Shiranui Sea, represent the greater shape of his film career—from his beginnings as a subversive director of state-sponsored educational films through his rich middle period consisting largely of films about the mercury-sick city of Minamata up to his late reworkings of footage taken on earlier journeys, with new soundtracks and new meanings added.

The releases of all five films—made available by Zakka on all-region discs in good to very-good transfers—come with helpful liner notes and film descriptions by Abé Mark Nornes and Sachiko Mizuno, respectively, as well as an additional brief essay by Takuya Tsunoda on The Shiranui Sea. While one might complain about the dearth of extras (which are limited to some short video interviews with Tsuchimoto on the Shiranui Sea disc and a digital booklet available on the Zakka Website), doing so would overlook the space that these releases fill. They are the first home-video releases outside Japan representing an artist commonly identified along with colleague Shinsuke Ogawa as his country’s greatest documentary filmmaker.

Though the films differ drastically from one another in several regards, they share their auteur’s implicit mark. “Once we filmmakers determine something in our mind, our own vision changes,” Tsuchimoto once said. “It won’t be worthy without that.” Always, he is somewhere slightly distant from the people in the scene, observing them, and opening himself up to be transformed by their interactions with him.

He was born in 1928 in Japan's Gifu Prefectureto a family whose patriarch was a minor government official. When he was very young his family moved to Tokyo, the city that he would call home until his 2008 death.Tsuchimoto would recall later in life how he was raised to worship the Emperor as a god, even serving in elementary school pageants at the Imperial Palace, then received a sudden shock at the end of the Second World War at learning that the Emperor was just a man. From then on—as he recounted at the 1995 Yamagata Documentary Film Festival—“I felt like I should never trust an adult, be suckered into fashions and fads, read best sellers, that I should take passionate debates with a grain of salt…I would only trust those of my generation, those with whom I saw eye to eye, all the while keeping a scrutinizing watch on those adults with whom I had to have contact.”

The self-proclaimed “pretentious little brat” joined the Japanese Communist Party and actively participated in Korean War protests while a student at Waseda University, from which his activism led to his expulsion. He subsequently searched for work until taking a job at the educational and public relations documentary studio Iwanama Productions, first as an assistant to other filmmakers, then as a freelance director in his own right. His first official film, 1963’s An Engineer’s Assistant, was commissioned by the Japanese National Railways in the wake of a train accident that killed 160 people, officially to educate the population about new safety measures and mechanisms. Tsuchimoto, however, ignored the new equipment in favor of focusing upon Japanese train conductors and engineers, who cheerfully demonstrate for the camera how they go about their daily work. Trains pass their marks in bright, colorful images as the men explain how their work requires them to take mandatory rest breaks for the sake of their staying alert and active. General health and safety are maintained by employers’ concern for their workers, and an image of a man operating train track levers with many different parts of his body suggests that the trains run smoothly thanks to a personal touch.

Though Tsuchimoto had disobeyed his original orders, An Engineer’s Assistant nonetheless received a good public reception. The subsequent On the Road: A Documentenjoyed no such luck. Tsuchimoto combined documentary and fiction for this work commissioned by the Tokyo Metropolitan Police in advance of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, enlisting professional actors to play a taxi driver and the man’s spouse as well as a number of real-life taxi drivers (in covert collaboration with a driver’s union) to essentially play themselves. “This film portrays the traffic war that goes on every day,” the movie’s opening voice-over would claim. The result was a piece of nightmarish Expressionism—the city as Tsuchimoto saw it from a cab driver’s point of view.

“Before trying to get amazing shots, or being impressed by them in a film, you should think about how they were achieved,” Tsuchimoto claimed late in life, referring specifically to On the Road’s looming image of an enormous truck wheel beside a much smaller cab—an image, he said, that was informed by a real driver’s constant fear of accidents. The film (unfolding largely at night) transitions between close-up images of the drivers in their cars and more distant views of vehicles backed up against each other along the crowded streets. These shifts occur as suddenly as do those in which the drivers themselves must leave endless congestion to avert crashes and infractions, both constant possibilities and both of which—their bosses warn—would reflect badly on the cab companies. At one point an electronic news crawl appears with an announcement of a young girl’s death and her mother’s injury from a taxi hitting them, immediately followed by news of the next day’s weather. Silent images such as these lend the film a surprising poetry, giving the sense that amidst the city’s perils, life simply continues.

The Metropolitan Police responded to Tsuchimoto's film by shelving it, which would keepOn the Roadout of public view for nearly forty subsequent years.Tsuchimoto, meanwhile, continued to work as an independent documentary filmmaker.Among the films he made soon afterwards were a documentary spotlighting the situation of a Malaysian exchange student threatened with deportation (Exchange Student Chua Swee-Lin [1965]); a chronicle of student radical activities at Kyoto University (Prehistory of the Partisans [1969]); and a documentary called The Children of Minamata Are Living (1965), made from a trip to a small seaside city in Kumamoto Prefecture, many of whose residents had suffered from mercury poisoning in their water. Though Tsuchimoto went to Minamata in good faith, acting out of a desire to record the truth of the residents’ conditions, he soon met with local resistance from families who had been exploited and manipulated by the media in the past, and assumed that he would bring more of the same.

Tsuchimoto was deeply shaken by the sensation of not having done justice to the people he filmed, and would later disown this first Minamata work. When he was approached five years later with the offer of making another film in Minamata, he opted to make it differently. As opposed to the former quick visit, he and his crew lived with a local woman for the five-month filming period, during which time he listened to the local people and created a film guided by their stories.

Minamata: The Victims and Their World opens with title cards contextualizing the situation. Minamata Disease—whose symptoms include restricted vision, damaged motor skills, and frequently death—was first diagnosed in 1953, and then declared a fifty-three-victim epidemic in 1956. Medical research soon showed that Minamata residents were growing sick (sometimes even in the womb) from wastewater and poisoned seafood. The chemical plant of the prosperous Chisso Corporation, Minamata’s economic lifeblood, had been responsible for dumping untreated mercury into the water, and in 1959 the victims and their families reached a reparations agreement with the corporation, part of which stipulated that no further legal or fiscal damages could be sought. Meanwhile, human damage continued: by 1970, 121 victims (46 of them dead) had been officially diagnosed, with many more sick unofficially.

It was at this point that Tsuchimoto and his crew entered Minamata, with the goal of getting the victims to relate their struggles. The film (originally 167 minutes long, and which Zakka offers in the 120-minute-long version that Tsuchimoto made for international release) consists largely of scenes in which the camera sits patiently facing a Minamata villager, observing his or her health and sickness while listening to the person talk. An older woman tells how she repeatedly filed legal complaints after her husband’s Minamata Disease-related death with the hope of the state placing blame for it; an older man describes how his wife has been driven so mad by the disease that their grandchildren call her “animal”; a series of parents present their children, unable to talk or walk, with even the teenagers still mentally infantile. The overriding demand that the film’s Minamata residents make is for recognition. The film leads up to an indelible climax in which a Minamata activist group storms a public Chisso shareholder’s meeting, and a woman who has lost both her parents to MD screams to the company president, “You can’t buy lives with money!”

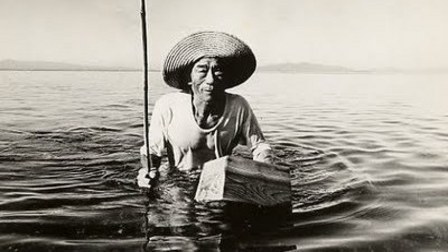

In making the film, Tsuchimoto faced a conundrum that he would explain in a documentary interview years later. “We must accuse what is wrong, what should not have happened,” he said, “but you do not want Minamata to perish in tragedy.” His logic is underscored by the balance in the film’s title. There were the victims, who had been made so by Chisso, but it was essential to Tsuchimoto that they not be defined only in relation to victimhood. Accordingly, the film takes care to present Minamata’s residents in their natural environments, whether through showing them cooking, walking in nature around their homes, or fishing. A sequence of a Minamata fisherman teaching the viewer how to catch, kill, and boil a squid (scored to a Bach piece) disarms through the gentleness with which the man seeks life in potentially poisoned water.

The “and” in Minamata: The Victims and Their World serves as a bridge connecting elements, which is how Tsuchimoto essentially saw his own role. Whether through glimpses of a microphone or simply the direction of a Minamata resident’s gaze, the viewer is always aware of the filmmakers in the scene. Unlike his peer documentarian Shinsuke Ogawa, who often filmed himself in radical sympathy with the rural people among whose ranks he lived, Tsuchimoto gives the sense of himself as always being a visitor from Tokyo, absorbing another’s circumstances without directly sharing them. The ethical distance he sought allows the film’s viewer to stand back and survey the scene in a position of empathy rather than sympathy, learning the context for a person’s situation along with him.

Tsuchimoto believed he could honor Minamata’s victims by recognizing their struggles as belonging to the larger problem of worldwide pollution poisoning many people like them. For the filmmaker, it was necessary not only to know what was happening, but also to understand why. He followed Minamata: The Victims and Their Worldwith three ninety-minute-long medical films, collectively called Minamata Disease: A Trilogy (1974, and currently unavailable for home viewing). In each film, doctors explained different aspects of the disease’s symptoms and development; in each case, Tsuchimoto requested that the doctors explain themselves in terms that he could understand, believing that this would enable viewers to understand as well.

His studies inspired him to make another long film about the water around Minamata, focused in particular on a process that he would later refer to as “the nature healing itself.” The opening, richly colorful image of The Shiranui Sea (which Zakka presents in a version prepared by Tsuchimoto for the film’s initial Japanese DVD release) is of an old man walking along the shores of Minamata Bay, where there has been a recent explosion in the oyster population.

The film goes on to show how the fishermen carefully separate poisoned fish from among the ones they catch, followed by an illustrated history (conveyed through diagrams and voice-over) of Chisso’s seventy-year-history of economically supporting the area, even while it was poisoning the residents.By the time ofThe Shiranui Sea's making, Chisso had formally admitted legal responsibility for Minamata Disease’s spread and was awarding lump sums to proven victims.The bureaucracy involved in getting one’s case heard and approved, however, was such that more than two thousand families were still awaiting a decision, including some that had filed their petitions years earlier.

Minamata’s people continue in the midst of this waiting. In contrast to Minamata: The Victim and Their World’s steady accumulation of revelations building towards catharsis, The Shiranui Sea works structurally through restoration, with the sense that humanity itself is self-healing. A visit to an institution organized for rehabilitating Minamata Disease youth shows teenagers practicing basic arithmetic and learning to walk with crutches, while images from Minamata: The Victims and Their World appear of the same young people as near-catatonic just a few years prior. A nurse laughs while recalling being surprised at a young male patient pinching her bottom and discovering his show of desire to be a sign of progress.

The Shiranui Sea depicts people learning to live with disease, and even potentially growing comfortable with it. One of the film’s subtle points, made through a variety of interviews with healthy-looking victims, is that a person can have Minamata Disease and still function normally, a point given in the spirit of alleviating the disease’s status as cause for social stigma. Witnesses speak of parents pulling their healthy children away from afflicted youth due to a mistaken fear of contagion; in contrast, a woman whose family has suffered tells Tsuchimoto, “I want everyone to know what Minamata Disease really is. And I want my children to pass the message on after me.”

As do other films throughout Tsuchimoto’s career, The Shiranui Sea posits education to be integral to a better future; far more than any medical knowledge, the film values learning how to be receptive to one’s fellow human beings. A long outdoor conversation between Tsuchimoto himself and a young male Minamata Disease patient expressing frustration over being socially excluded results in the filmmaker negotiating how to respond once the young man asks to travel across Japan with him. Tsuchimoto cannot bring the boy, of course, but the image of him struggling with himself over how to reply honestly shows him learning how to grant the young man’s even greater wish: to be treated “like an adult,” with respect. This moment stays in the mind during a late scene of Tsuchimoto and his crew enjoying a surprise seafood feast made for them by Minamata’s fishermen, as well as during the film’s closing shots of fishing boats on the water. The film suggests that outsiders must value Minamata’s way of life for Minamata Disease to be fully cured, while showing that way of life to be continuing regardless.

In the years following, Tsuchimoto presented his Minamata work as educational films on travels throughout the world, including a mid-1970s visit to First Nation communities in Canada who had suffered an outbreak similar to Minamata Disease. He would also periodically return to making films about Minamata, completing fifteen in total by the time of his death. (A sixteenth was subsequently made from some of his unused footage by Motoko Tsuchimoto, his wife and frequent editor.) His goal in doing so, he claimed, was to leave records of the area’s suffering and development. “The history of the Minamata Disease is not yet over,” he said in 2006, at a time when Chisso was still paying reparations to victims and their families (as it has continued to do until at least as recently as 2010, the same year in which the United Nations formed the Minamata Convention on Mercury in order to lower worldwide emissions), and as Minamata itself was turning from a fishing city into an industrial one. “Nobody prevented the new lives to be born in fear of the Minamata Disease.”

As Tsuchimoto continued to reflect on his relationship to Minamata in cinema—changing his positions between films on ethical issues such as whether to give victims’ names—he also worked on other film projects. They included a postmortem record of the writer Nakano Shigeharu and several films depicting artists’ efforts to render the effects of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. In the mid-1980s Tsuchimoto led a group of filmmakers on a goodwill mission to Afghanistan, resulting in the feature-length documentary Afghan Spring (1989), which focuses largely on farming families as they work their land and mourn the losses of loved ones to the Soviets. He returned to edit unused material from this period shortly after the 2001 U.S. and NATO invasion of Afghanistan, leading to the final two films in Zakka’s Tsuchimoto collection.

“I am losing the ideological radicality that I used to have, and now I am amazed about how much people are capable of,” Tsuchimoto said late in life. This sentiment could easily be applied to both of his 2003 Afghanistan films, each of which runs a little over half an hour and features a Tsuchimoto voice-over recorded in order to replace the footage’s lost original soundtrack. One of them, Traces: The Kabul Museum 1988, was born out of loss—specifically, the news that over seventy percent of the Kabul Museum’s collection of ancient artworks had been destroyed or stolen following the 1992 collapse of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan’s government, which preceded the Taliban’s takeover.

Tsuchimoto’s film—the world’s lone publicly released film record of the museum’s collection—gives a record of some of what has been lost. After a brief prologue presenting desert valleys and Silk Road routes from which the ancient works came, the bulk of Traces consists of views of museum objects accompanied by Tsuchimoto’s voice giving their origin and social function in a sort of audio guide. The clay demon masks, ancient coins, Bodhisattva wall painting, and other Mediterranean and Asian treasures (several of which were glimpsed much more briefly in a Kabul Museum sequence of Afghan Spring) are often presented from at least two views: framed within glass cases, and by themselves against a black background, depicting the items both as visitors to the museum would have seen them and on their own, seemingly freed from time.

The film Another Afghanistan: Kabul Diary 1985 juxtaposes time and timelessness through images of a living human society. As images pass of some of the city’s 1.5 million members walking along streets and through open-air markets, Tsuchimoto recalls a relatively peaceful period during his time in the country, when Kabul residents conducted their daily business (including Muslim prayer, asserted here as a simple fact of life) under stable Soviet rule. The filmmaker tells with brief illustrated accompaniment about how an overwhelming majority of the multiethnic city’s residents were illiterate, effective land reform policies were slow in coming, and the city’s number of orphans were rising without homes ready for them.

Yet Another Afghanistan balances hardship with happiness and glimpses of potential prosperity. Young people appear dancing and playing music in the street, a sight that Tsuchimoto reports he and his crew encountered often; and throughout the film float images of blooming flowers, one of which Tsuchimoto says he glimpsed adorning a cannon barrel in a 1978 newspaper story about the country’s Saur Revolution (instilling the subsequent communist government) and which appears again throughout Kabul’s streets towards film’s end as people march to celebrate the revolution’s sixth anniversary. As young men and women from different classes wave flags, Tsuchimoto reflects that the children born into the revolution are now nearing thirty years old.

The film ends with a freeze-frame of the crowd and the filmmaker’s off-screen words: “This film was shot some eighteen years ago, but it feels as if we are looking at Afghanistan’s future. Am I the only one who feels this way?” Tsuchimoto knew about the wars that would come in the years following these images, but closed his film by looking forward while inviting others to share his hope.

****

Zakka Films’s Noriaki Tsuchimoto page can be found here.

The Chisso Corporation changed its name to Japan New Chisso (JNC) in 2012. Motoko Tsuchimoto continues to own and run Cine Associe, the production company she founded with Noriaki Tsuchimoto.

Nearly all Noriaki Tsuchimoto quotes used in this article can be found in the following three sources: “Tsuchimoto Noriaki,” an excellent interview conducted with the filmmaker at the 1995 edition of the Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival (YIDFF); Toshi Fujiwara’s 2007 feature-length documentary portrait Cinema is About Documenting Lives: The Works and Times of Noriaki Tsuchimoto; and the short documentary Noriaki Tsuchimoto on Documentary Film, edited by Motoko Tsuchimoto from lectures by her husband and available as a special feature on the Zakka Films DVD of The Shiranui Sea. Noriaki Tsuchimoto’s extensive writings remain largely unavailable in English.

Thanks to Aaron Gerow, John Gianvito, Justin Jesty, Seiko Ono, and Takuya Tsunoda for research help.

Aaron Cutler works as a programming aide for the São Paulo International Film Festival and maintains a film criticism site, The Moviegoer.

Copyright © 2013 by Cineaste Magazine

Cineaste, Vol. XXXIX, No. 1