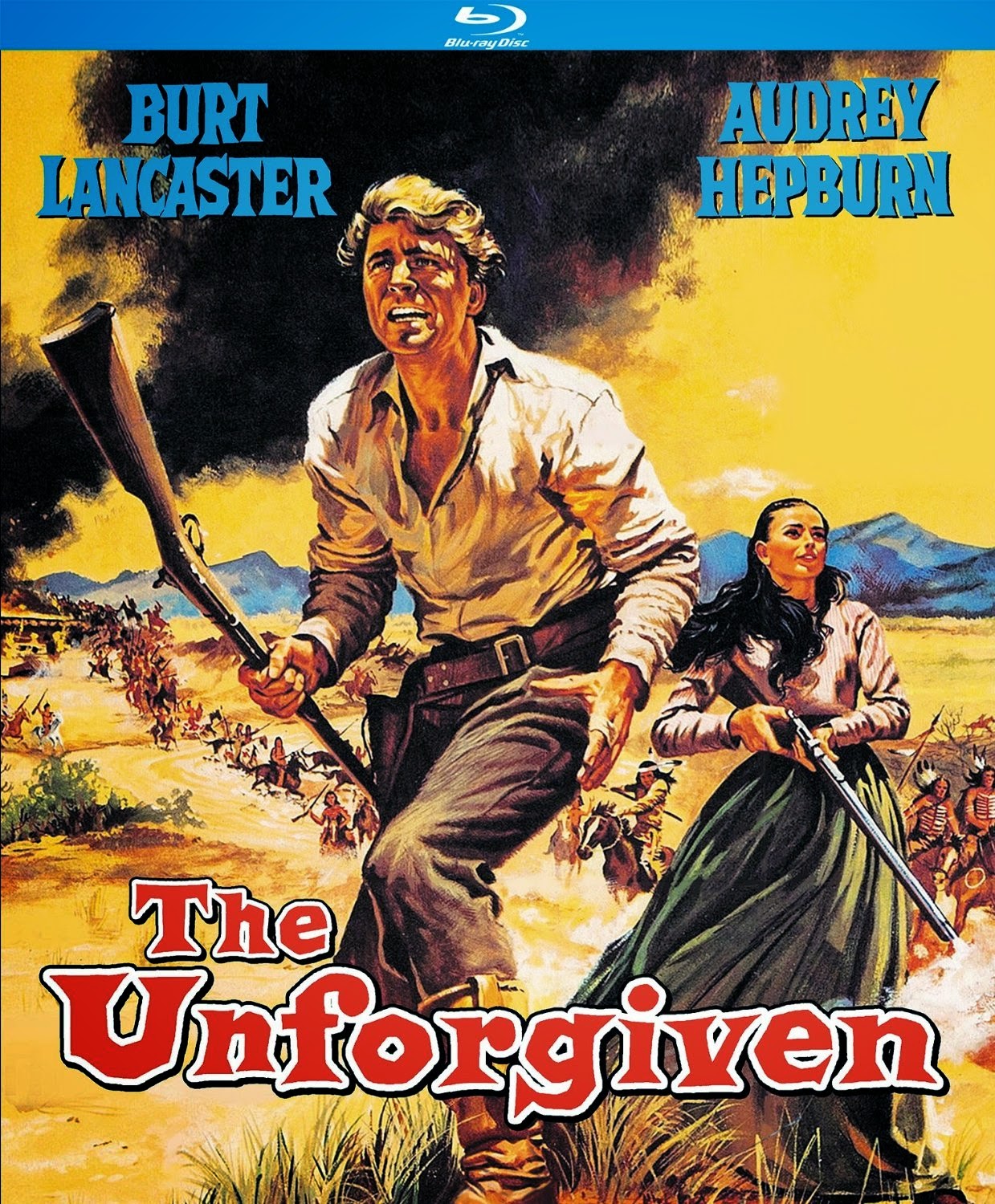

The Unforgiven (Web Exclusive)

Reviewed by Christopher Sharrett

Produced by Harold Hecht, James Hill, and Burt Lancaster; directed by John Huston; screenplay by Ben Maddow; based on a novel by Alan Le May; cinematography by Franz Planer; edited by Russell Lloyd; music by Dimitri Tiomkin; art direction by Stephen Grimes; costume design by Dorothy Jeakins; starring Burt Lancaster, Audrey Hepburn, Lillian Gish, Charles Bickford, Audie Murphy, Doug McClure, John Saxon, and Joseph Wiseman. Blu-ray and DVD, Color, 122 min., 1960. A Kino Lorber release, www.kinolorber.com.

Several of John Huston’s late-period films were treated cavalierly by their studios and almost lost, notably The Kremlin Letter (1970), one of the most controversial, uncompromising espionage films about the amorality of the Cold War. Fortunately, it was rescued (if in truncated form) by both Eureka! Entertainment and Twilight Time video. Huston’s The Unforgiven never faced the threat of oblivion, yet this remarkably revisionist Western, based on a novel by Alan Le May (author of the source for The Searchers), has been nearly forgotten, confused with Clint Eastwood’s 1992 Oscar-winning film of the same title, minus the definite article.

I hold the Eastwood film, his farewell to the genre that made him a star, in some esteem. Yet, today it looks forced and mannered, preoccupied with overturning every single convention of the Western. The Unforgiven, at its release and now, is shocking in its revisionism, depicting the racism of white “settlers” in postbellum Texas with ferocity, and a passion representative of late Hollywood narrative.

The Zacharys are a pioneer family whose patriarch, William, is long dead, killed in “Injun wars” by Kiowa Native Americans. In his place is matriarch Mattilda (Lillian Gish) and eldest son Ben (Burt Lancaster), just returned from a cattle drive to Wichita. His siblings Cash (Audie Murphy), Andy (Doug McClure), and adopted daughter Rachel (Audrey Hepburn) are overjoyed at his return, but the family is far from at ease with itself. The women have been bedeviled by a ghostly, emaciated, Bible-verse-spouting lone rider clad in a filthy U.S. Cavalry uniform named Abe Kelsey (the magnificent Joseph Wiseman). Kelsey holds a secret—Rachel Zachary is actually a Kiowa child, kidnapped after a genocidal raid on a Kiowa village perpetrated years earlier by Kelsey and Will Zachary. Kelsey’s son was kidnapped and killed in revenge.

Kelsey’s visits become frequent, as do demands from local Kiowa to return Rachel. Ben Zachary argues with Kiowa visitors that Kelsey is simply insane, then dispatches Native wrangler Johnny Portugal (John Saxon), an expert horseman, to track down Kelsey in order to try him for his slanders. Kelsey is brought back to a tribunal/lynch mob made up of the Zacharys and neighboring business partners, the Rawlins, led by crippled, Bible-thumping patriarch Zeb (Charles Bickford) and his near-lunatic wife Hagar (June Walker). The good feeling that the two families enjoyed upon Ben’s triumphant return from Wichita dissolves when the white community becomes disturbed by the very notion of an Indian in their midst. The conflict intensifies when the Rawlins’ idiot son Charlie (Albert Salmi) courts Rachel, an abomination in the eyes of Kiowa (since Rachel is their kidnapped child), a vile outrage to the white community.

Burt Lancaster and Audrey Hepburn as Ben and his adopted sister Rachel in John Huston's underrated The Unforgiven

In a disturbing, out-of-nowhere moment, Mattilda Zachary hangs Abe Kelsey as he tells his tale to the mob (the community explicitly portrayed as nothing more). Zeb Rawlins is convinced that Kelsey wasn’t a liar, and looks with suspicion on Rachel, whose dark complexion is no longer attributed to the sunlight. Rawlins demands that the women of the group remove Rachel’s clothing—the bereaved, monstrous Hagar screams, “Strip her down, strip her down naked!” Earlier, when an unknowing Rachel tries to comfort Hagar over the death of Charlie, the old woman responds with uncontrolled, crazed fury: “You’re a red-hide nigger as ever was!” The film reminds us, unlike so many Westerns, that the “Wild West” took place not in a historical vacuum but in the awful white racist climate of Reconstruction and post-Reconstruction America. Racism was at a new peak as the country, North and South, showed contempt for redressed grievances of freed people, and a new hatred toward Native Americans (in part as a way of diverting attention from the economic depression of the 1870s).

The troubles disrupting the Zacharys include more than racism. Rachel desires brother Ben, who laughs off his adopted sister’s cuddles with good-natured scolding, but his attraction to Rachel is obvious; it bolsters the film’s tension as the racial turmoil increases. Incest isn’t really a threat (the two aren’t “blood kin”), but the film’s handling of the topic, recurrent in one way or other in the Western, is boldly asserted here, and without moralizing—Ben ultimately pledges himself to Rachel.

The racism facing the Zacharys is as much internal as external. Cash, the middle brother, tells Ben he can’t stand the “stink” of Kiowa. He snidely calls the Native wrangler Johnny Portugal “paleface.” When he learns that his sister is “one of them,” he flees to the Rawlins family, but, blood always being thicker, returns at the last moment to assist Ben and siblings in their last stand against the aggrieved Kiowa. As Cash, Audie Murphy delivers his finest performance. This most decorated soldier of World War II was offered Hollywood contracts as his prize—in thoroughly undistinguished oaters best ignored. Here, Huston makes him work; the result is startling.

For that matter, it is hard not to note this film’s very distinguished cast, all of whom are no longer with us. This isn’t surprising given that the film is over fifty years old. Lillian Gish, a matriarch of the cinema itself, is superb as the cultured mother (she plays Mozart on a piano given her by Ben) who has learned to be an accomplished liar to protect the adopted daughter brought to her by her late husband; at the time, the two were grieving over the death of one of their own children. Mattilda’s recounting of her nursing infant Rachel is one of the most touching scenes of Sixties cinema. Audrey Hepburn is never quite plausible as a Native American, but her performance is very credible, showing Rachel to be a cheerful emblem of nature itself until her innocence is lost. After learning her origins, Rachel’s loyalties are divided, especially as she meets, and ultimately kills, the young Kiowa man who is her actual brother. Charles Bickford’s Zeb Rawlins is perhaps a character too often repeated by him, but here there are no excuses, no qualifiers for undisguised race hatred.

A word about Burt Lancaster, whose Hecht-Hill-Lancaster company was a moving force in this film, a work that reasserts Lancaster as not only late Hollywood’s most energetic, dynamic actor, but also one of its most progressive, whose social commitments made him a forceful presence in Hollywood liberalism when the term had real meaning, suggesting something beyond “liberal,” today connoting less than milquetoast ideology. In the year of The Unforgiven, Lancaster also enthusiastically made Elmer Gantry (made in the sense of advocacy as well as starring in it), a flawed film based on a portion of Sinclair Lewis’s superb novel, but a movie that one could hardly imagine today (given the power of the Religious Right), taking on as it does not only evangelism but organized Christianity itself.

The Unforgiven is not without problems. John Huston was dissatisfied with it, wanting a far more scathing critique of racism in America, naysayed by financial backers. The finished film, as critical as it is of white America, maintains stereotypes. When the Kiowa begin their war music, Mattlida is encouraged by Ben to play Mozart on the family piano—in this, the film anticipates Cy Enfield’s Zulu, with British regulars singing “Men of Harlech” while the Zulus chant “jungle music.” Whites are depicted as a civilizing force, the racial other mostly barbaric, a surprising slip for a sophisticated film.

The Unforgiven’s atmospherics are notable, including Franz Planer’s widescreen, wind-swept cinematography, and most especially Dimitri Tiomkin’s atypical horn-and-woodwind driven score. Conducting the Orchestra of the St. Cecilia Academy of Rome, Tiomkin helps the film achieve an authentically epic scope. His approximation of “Indian music” might be criticized, but it always struck me as interesting, even somewhat experimental, especially the “nachtmusik” the Kiowa play before their attack on the Zacharys. The film adds some inflections to the Western in its period detail; the Zacharys live in a soddy, a house built into the side of a hill to provide security from foes and the elements. Zeb Rawlins’s crutches are made from the stocks of two rifles, something that rings true as period image while also telling us something about their user.

MGM released a very good DVD of The Unforgiven over a decade ago. The Kino Lorber Blu-ray lacks, to my eyes, the color saturation of the earlier release, but makes up for it with its remarkable clarity, detail, and depth of field. And it’s good to see that a company previously known for releasing foreign films exclusively is now sharing the struggle to restore old Hollywood.

Christopher Sharrett is professor of communication and film studies at Seton Hall University.

To purchase Kino Lorber’s Blu-ray or DVD of The Unforgiven, click here www.kinolorber.com.

Copyright © 2014 by Cineaste Magazine

Cineaste, Vol. XL, No. 1