Visions of Avant-Garde Film: Polish Cinematic Experiments from Expressionism to Constructivism (Web Exclusive)

by Kamila Kuc. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2016. 227 pp., illus. Hardcover: $75.00 and Paperback: $35.00.

Reviewed by Stuart Liebman

Recovery of the heritage of early twentieth-century European reflections on the cinema and a re-energized attention to the avant-garde filmmakers who began to explore the medium’s unique artistic potential has been a significant feature of the Cinema Studies discipline since its arrival in American universities during the late 1960s. Quite a few of us who started this research when we entered the fledgling academic field more or less at its inception were seeking a kind of theory and praxis beyond standard Hollywood norms that could justify our commitments to the vanguard films of the New Waves imported from France, Italy, and Germany as well as those percolating at home in the New American Cinema. Perhaps, too, our exploration of these half-century-old, radically unorthodox films and speculations with their conceptual links to the major twentieth century modernist art movements from Cubism and Expressionism to Dada and Surrealism was motivated by the hope that they would supply a kind of intellectual pedigree that could buttress our decision to pursue a subject generally regarded with indifference, condescension, or even disdain by many, perhaps most, of our peers in the Humanities.

We first avidly plumbed what was then available—Pudovkin’s or Eisenstein’s theoretical pronouncements on films in Ivor Montagu’s and Jay Leyda’s translations. These provided initial insights into the innovative “montage” strategies they had developed, which were being explored anew by many political filmmakers in the 1960s. Then, over the course of the 1970s, texts by pioneering cineastes like Bela Balazs, Lev Kuleshov, Hugo Munsterberg, and René Clair either appeared for the first time or were republished (thanks to Dover) while I joined others in exhuming and translating the writings of virtually forgotten 1920s figures such as Louis Delluc, Germaine Dulac, and Jean Epstein, now branded as “French Impressionists.” Accessible versions of important texts on cinema by Walter Benjamin, Bertolt Brecht, and Siegfried Kracauer also appeared, challenging notions about film as art and its social functions. From the 1980s onward, moreover, in what had already become an established scholarly niche, the pace of revealing and making available texts only increased. Annette Michelson’s edition of Vertov’s texts (1984); the impressive anthologies of writings by early French cineastes (Richard Abel’s two-volume anthology of their writings, 1988); Ian Christie and Richard Taylor’s accurate translations of Russian texts that enlarged the scope and refined our understanding of early Soviet film theoretical discourse; up to the very recent publication of Anton Kaes’s (and several co-editors’) massive anthology The Promise of Cinema. German Film Theory 1907-1933 (2016)—all of these contributions and many others have helped immeasurably to make accessible an often suppressed and then long forgotten alternative past of the medium.

For good reason, Kuc makes little reference in her historical survey of the work of avant-garde filmmakers in Poland to the early Polish film industry that remained primarily a minor producer of melodramas for a largely domestic audience, which were disdained by Polish cultural elites. Instead, she focuses on the smaller scale, personal works she characterizes as “artisanal” that were closely related to early modernist experiments in literature and art. As she admits, however, there were precious few films that can be characterized in this way for the first twenty-five years or so of filmmaking in Poland, so the opening chapter focuses on purported antecedents to the eventual handful of projects that were later launched.

Her descriptions of some of the earliest ideas and productions by Polish cineastes are interesting though the conclusions she draws are not entirely convincing. For example, she locates certain features of the ideas animating later avant-garde filmmakers in the thinking of Zygmunt Korosteński. As early as 1896, he championed film as an objective record of important historical developments that were worthy of archival preservation. Bołesław Matuszewski’s brief reports, modeled on the first Lumière movies, arguably realized Korosteński’s vision by documenting key international political events such as state diplomatic visits or portraits of dignitaries. Both men wanted to enlist the new medium to serve the patriotic purpose of raising Polish national consciousness. Such an effort, however, seems quite foreign to the stylistic and political concerns of the emerging West European and Soviet avant-gardes. Kuc’s claim that Korosteński’s and Matuszewski’s efforts later bore fruit in the synthetic collage films made by several Polish artists in the 1930s with radically different political intentions in mind therefore seems quite tenuous. Kuc should have restricted herself to the more modest observation that the primary value of these early documentary initiatives was to overturn the legacy of romanticism that had dominated Polish literary and artistic circles since the nineteenth century and by doing so helped clear the ground for more modernist work and ideas to grow.

In the mid-1910s, a new tone emerged in Polish film circles. The influential cultural critic, Karol Irzykowski, had followed the efforts of the French “Film d’Art” company and in 1913 pushed for the production of similarly “artistic” stories in films. His version of an “art cinema,” however, can hardly be thought of as an avant-garde initiative; he merely aimed at elevating the caliber of the stories in order to satisfy middlebrow cultural standards.

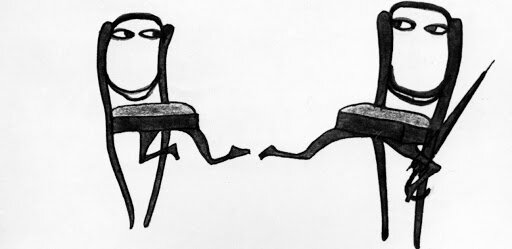

Feliks Kuczkowski’s Flirt Krzesełek (Flirting Chairs, 1917).

Only when more experimental-minded critics and artists pursued the critic Kazimierz Wyka’s notion of a cinema independent from other art forms and free of social obligation could the idea of a uniquely cinematic art for its own sake emerge. Feliks Kuczkowski was apparently the first to attempt to give shape to such ideas in the late 1910s when he launched his “synthetic-visionary,” stop-motion animated film project, Flirt Krzesełek (Flirting Chairs, 1917). “He wished to discover what is peculiar to the language of film,” Kuc writes, and she describes several of his other attempts to do so. Unfortunately, apart from a few stills none of this work survives. Nevertheless, the family resemblances between his proposals and working documents and those of a number of like-minded artists across Europe—Wassily Kandinsky, Léopold Survage, Ladisław Starewicz and later Oskar Fischinger as well as his countrymen, Stefan and Francziska Themerson—are sufficiently clear to acknowledge Kuchkowski’s efforts as vanguard in spirit.

For this reader, Kuc’s claims about an active avant-garde scene really only commence when, from the 1920s on, a commitment to a purer, more abstract and more modernist art increasingly captured the imaginations of the Poles who cared about an alternative, noncommercial future for cinema. Kuc notes how the new conceptual investigations were increasingly leavened by ideas imported from both East and West. For example, the concept of photogénie developed in the writings of Warsaw-born Jean Epstein, perhaps the most searching theorist among French independent filmmakers at the time, proved very stimulating to his erstwhile countrymen. Regularly published in vanguard Polish journals, his essays reconceived the cinematic image not as a record of facts or teller of tales but as a camera-filtered device to generate material forms that unlocked labile, even mystical dimensions of meaning. In such a world pictured on screen, telling stories was irrelevant. These tendencies were further encouraged, moreover, by the roaming chronologies and illogical connections in the free verse poetry of another Polish emigré— Guillaume Apollinaire. With such examples in mind, the critic Jalu Kurek argued that films should be conceived as fluid “optic poetry” that could provide spectators with aesthetic delight.

Stefan and Franciszka Themerson’s Aptekaka (Pharmacy, 1930).

The models for the imagery vanguard Polish films developed shifted over time although the destruction of many works and the book’s limited number of illustrations make the look of their works hard to visualize. Kuchkowski’s quasi-Expressionist drawings for his animated film apparently had few followers. Later in the decade, interventions by the German Hans Richter, the maker of Rhythmus 21, and the Polono-Russian artist Kazimir Malevich advocated the spare geometric forms associated with international De Stijl and Russian Constructivism; again, few filmmakers pursued their recommendations. On the other hand, the shadowy, black and white imagery of Moholy-Nagy’s and Man Ray’s “photograms” clearly inspired the filmmaking team of Stefan and Franciszka Themerson to make Aptekaka (Pharmacy, 1930), which is one of the few films Kuc discusses that can actually be watched on YouTube. The young couple used both positive and negative imagery of glass bottles moved by spectral hands through shifting light sources presented in forward-, stop-, and reverse-motion. These arguably distinctive cinematic techniques enabled them to realize a sensuous modernist film poem meant for the eyes alone. As such, Apteka as well as their Europap (1931–32) certainly represent distinctive highpoints of the early history of genuinely vanguard artisanal productions in Poland.

The final chapter in Polish avant-garde film activities covered by Kuc occurred in the 1930s when the Themersons, along with artists and critics like Tadeusz Peiper, Janusz Maria Brzeski, Jalu Kurek and Kazimierz Podsadecki, embraced Dadaist and Constructivist concepts of montage juxtapositions to infuse satirical or absurd social themes into their work. The Themerson’s Przygoda człowieka poczciwego (The Adventure of an Honest Man, 1937) is an example of this trend that is also available on YouTube.

The montage aesthetics behind what Kuc calls their “catastrophist” city symphonies gradually shifted in a more overtly political direction. Some critics and filmmakers distanced themselves from the notion of art for art’s sake, claiming “that utilitarian considerations in production technology could achieve results similar to those of aesthetic considerations.” Others favored the use of photomontage and emphatic editing to achieve political messaging with an“aesthetics of maximum economy.” By decade’s end, the appeal of Soviet-style film montage and agitprop aesthetics grew, especially among the left-wing progressive filmmaking group START. An assessment of this group, whose members included future stalwarts of the postwar, communist-controlled film industry Aleksander Ford and Wanda Jakubowska, however, falls outside Kuc’s purview even though the Themerson’s Calling Mr. Smith (1943), made while in wartime exile in London, may be said to share some of START’s strategies and goals.

The Themerson’s Calling Mr. Smith (1943).

Energetically researched and carefully documented, Kuc’s study—which the rather tedious signposting she employs (“In this chapter I will…”) reveals was clearly once her doctoral dissertation—is, for all its merits, less illuminating than it might have been. Her short sketches of the lives and ideas of Polish intellectuals who were passionate about the future of cinema are welcome because they are virtually unknown to Western scholars. Her accounts of what each stood for or made, however, is too often limiting or confusing. Subjected to overlapping and often contradictory influences, their writings indulged in resounding but vague statements of general principles. Kuczkowski wanted to construct an “ideal synthetic-visionary film” [that] “should contain elements of Expressionism.” We are left guessing what Kuczkowski means because Kuc is more inclined to repeat than to analyze these notions. And when she writes that Polish “Constructivists” believed that an object should be made “according to its own principles,” in “the DISCIPLINE of harmony and order,” the depth or originality of their ideas is hard to assess. Were they simply parroting ideas imported from elsewhere? Did their ideas significantly change over time? Finally, she leaves a gaping lacuna in her account when she nowhere describes, let alone analyzes, how at least the Polish educated public received or responded either to the avant-garde ideas or productions.

Perhaps the principal reason for my dissatisfaction with her study is that Kuc simply excerpts snippets of texts rather than presenting them in extenso and subjecting them to more concerted scrutiny. A better decision would have been to include translations of some of the key articles her subjects wrote so that readers could better evaluate how useful, striking, or indebted to foreign sources their notions were. The main text of the book, after all, is only 141 pages in length. The scholarly apparatus (footnotes, filmography, and an admirably comprehensive, thoughtfully arranged bibliography) does take up an additional 84 pages, but surely some additional space could have been found for a more representative selection of longer texts whose ideas and arguments would have confirmed that their characterization as avant-garde was fully warranted.

Stuart Liebman is professor emeritus of film studies at Queens College and the CUNY Graduate Center.

Copyright © 2020 by Cineaste Magazine

Cineaste, Vol. XLVI, No. 1