From Innocence Redeemed to Decadence Damned: Two Early Silent Films by Jean Renoir Now on Blu-ray (Web Exclusive)

by Stuart Liebman

La Fille de l’eau

Directed by Jean Renoir; screenplay by Pierre Lestringuez; cinematography by Jean Bachelet and Alphonse Gibory; set design by Jean Renoir; music for the new restored version by Antonio Coppola; starring Catherine Hessling, Pierre Philippe (Pierre Lestringuez), Pierre Champagne (Justin Crépoix), Maurice Touzé, Pierre Renoir. Audio commentary by Nick Pinkerton. Blu-Ray, B&W, silent with French and English subtitles, 83 min., 1925. A Kino Lorber release.

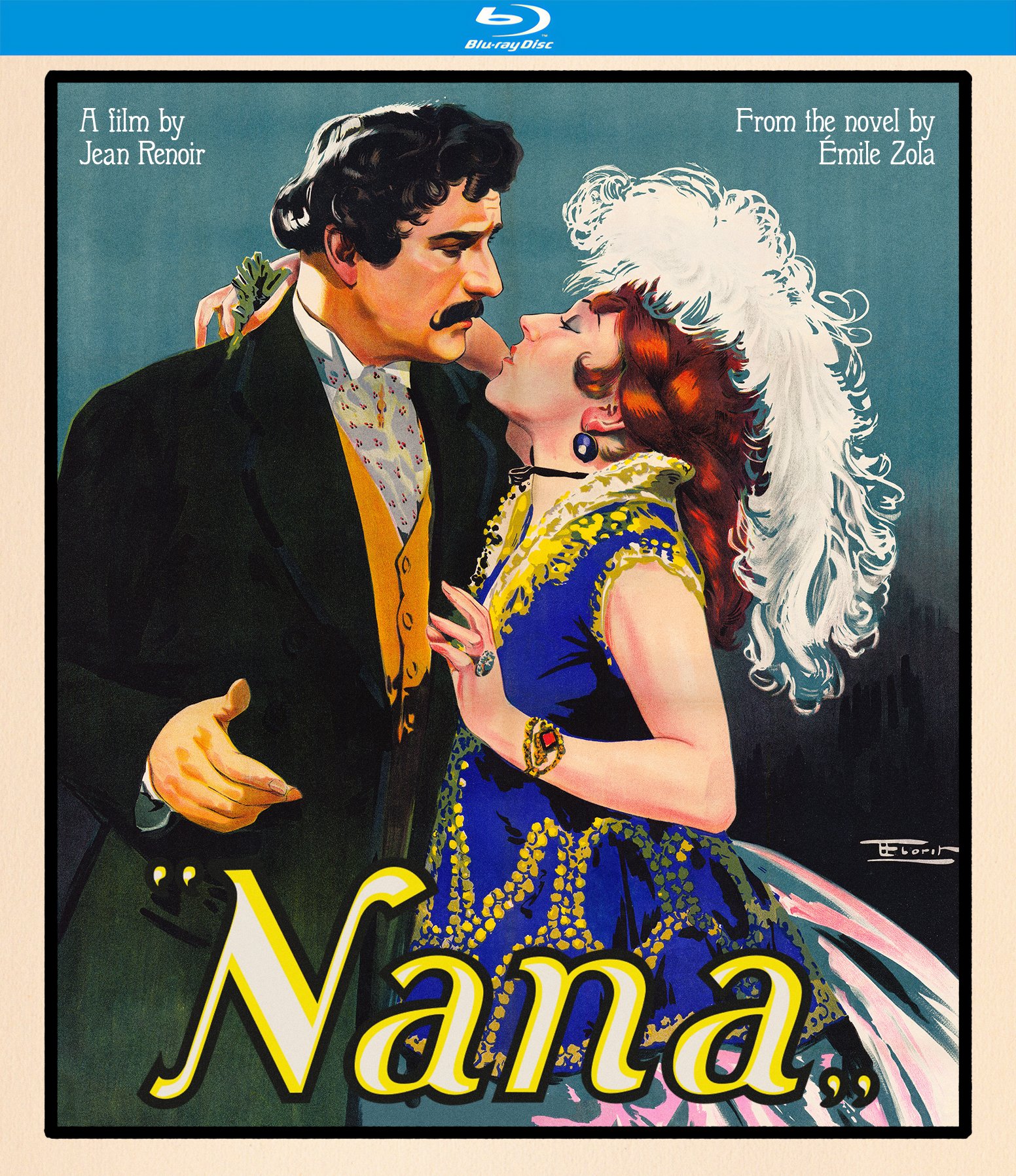

Nana

Directed by Jean Renoir; Screenplay by Pierre Lestringuez from the novel by Émile Zola and adapted by Jean Renoir; cinematography by Jean Bachelet and Edwin Corwin; set design and costumes by Claude Autant-Lara; edited by Jean Renoir; music for the new restored version by Antonio Coppola; starring Catherine Hessling, Jean Angelo, Werner Krauss, Raymond Guérin-Catelain, Valeska Gert, [Karl] Harbacher, Claude Moore (Claude Autant-Lara), Pierre Philippe (Pierre Lestringuez), Pierre Champagne (Justin Crépoix). Audio commentary by Nick Pinkerton. Blu-Ray, B&W, silent with French and English subtitles, 168 min., 1926. A Kino Lorber release.

I sometimes wonder what Jean Renoir might have been thinking in 1971 as he leafed through the pages of a highly anticipated new book about his filmmaking career. Specifically, what did he think when, in the very first chapter, he encountered several sharply disparaging comments about his first ventures in silent cinema? When he read that Renoir “was still preoccupied with his performers and not yet able to subordinate acting to the demands of storytelling on film,” would he have nodded abashedly? How would he have responded to the author’s further charges that “the early [silent] films give the impression Renoir had not yet found reliable guidelines for his editing; the shots follow one another with no logical or dramatic coherence?” Even though such cutting comments (pun intended) were buffered by rather empty praise granting that Renoir’s silent movies were “full of a charm which testifies to the genius of its creator,” the remarks about his alleged editing malfeasance and too generous collaboration with actors must have been hard to take, especially when the writer airily concluded that these early works were only important in so far as they served the filmmaker’s technical apprenticeship.[1]Finally, what reflections might have passed through the mind of the venerable master of French cinema as he came across the writer’s almost cavalierly blunt coup de grâce in the penultimate paragraph: “For it must be admitted that while his silent films foreshadowed what was to come, there is no comparison between even the best of the silent and the worst of the sound films.”

André Bazin’s book on Jean Renoir, in which he dismissed the director’s early films.

The book Renoir almost certainly did peruse upon its publication in 1971 was, of course, Renoir, nominally authored by the great French film critic, André Bazin. Although his name is on the cover, the volume appeared thirteen years after Bazin’s premature death from the cancer that had impeded its completion. (As an homage to his mentor and virtual stepfather, François Truffaut had skillfully assembled Bazin’s fragments and notes about Renoir and then augmented them with his own contributions as well as those by several of his colleagues.) The harsh comments I just quoted, however, were by Bazin himself and their uncharacteristic lack of generosity puzzles me. After all, for many years he was Renoir’s foremost critical champion. The thirty-one-year-old Ciné-Club enthusiast who was already a gracious, promising writer about cinema, and the sixty-five-year-old filmmaker, whose charm and expansive capacity for friendship were central to his persona, had bonded after their first brief meeting in late 1949. Moreover, by the time Renoir returned to France in early May 1951 from his decade-long exile in Hollywood by way of India, their relationship had deepened. Bazin had become a senior editor of Cahiers du cinéma, the recently established flagship journal for new thinking about cinema in France and its influence would soon spread around the world. To celebrate Renoir’s return, Bazin enlisted several of the young cinéastes who regularly contributed to the magazine and devoted the January 1952 issue to lionizing Renoir both as an auteur and as the essential French filmmaker. At the time, few greater critical tributes could be imagined. Over the next seven years, however, even as Bazin’s esteem for Renoir’s work from the 1930s remained profound and his affection for the man only grew, he obviously never was able to embrace—one should perhaps even say he dismissed and undervalued—Renoir’s ambition and achievement in his silent works.

Kino Lorber’s recent release of restored versions of Renoir’s first two silent films offers an opportunity to revisit Bazin’s harsh and, in my opinion, quite condescending characterization of their interest and stature. La Fille de l’eau (1924; renamed The Whirlwind of Fate for its English-language release) was the second film that Renoir had helped to produce and the first he directed to be released in France before its wider distribution in Europe and the United States. His second feature, Nana (1926), was an even more complex and significant enterprise. Renoir adapted, co-scripted, directed, and personally financed Nana based on Émile Zola’s provocatively racy—indeed, distinctly scandalous—1880 novel sensationalizing the decadence of French society under Emperor Napoleon III.

Each film can be faulted for one aspect or another, of course, but these certainly do not primarily lie in any lack of technical skill or failings of artistic judgement on Renoir’s part that Bazin alleged. Rather, Bazin seems to have been blinded by the theories he developed about the medium that he had conjured from Renoir’s films of the 1930s and especially once these ideas were supplemented by examples from the Italian neo-realist films that emerged after the end of World War II. The principles of cinematic realism he constructed as the standards of cinematic value seemed to blunt his critical intelligence so that he could not give sufficient credence or credit to the interest and strengths of Renoir’s early ventures which were rooted in alternative, if less theorized, aesthetic conceptions of the medium.

Catherine Hessling as Virginia in Whirlpool of Fate.

La Fille de l’eau is best thought of as an experimental melodrama à l’américaine. Its plot, drafted by Renoir’s pal, Pierre Lestringuez, reflects their shared enthusiasm for the American movies that flooded French movie screens after World War I. The plot involves the perilous misadventures of a young girl—called Gudule in the French original and Virginia in the English version—who lives on a barge plying France’s tranquil backcountry waterways. When her father accidentally drowns, her dissolute uncle Jeff takes over, drinks himself into bankruptcy, and finally attempts to rape her in a carefully edited scene very much indebted to D.W. Griffith’s stylistics. She manages to escape his clutches only to fall in with a “gypsy,” “the Weasel” “La Fuine” (sic), who offers her shelter but soon leads the naive girl into a life of petty theft. When a dispute with a farmer leads “the weasel” to set fire to his haystacks, a raging mob of the farmer’s friends (including Renoir’s older brother Pierre) takes revenge by torching the caravan which had become her temporary home. The weasel barely gets away; Virginia is once again forced to flee; hungry, cold, and alone in the forest, she becomes feverish and delirious. She dreams that Georges, a young bourgeois from a prominent local family whom she had met, rides to rescue her on a white horse—admittedly a cliché symbol. Luckily for her, her dream anticipates what actually happens. Nursed back to health, she becomes part of Georges’s household and the two fall in love.

The dangers Virginia faces, however, are not yet over. Straight out of a nineteenth century melodrama, the evil, hulking Jeff returns and repeatedly extorts money that the family had entrusted to Virginia, leading Georges to doubt her integrity. Eventually, however, in classic melodramatic style, Georges chances to overhear Jeff threatening Virginia. A ferocious fight ensues, a defeated Jeff floats away down the river and the young people are reunited as the entire clan leaves on a trip to inspect their holdings in colonial Algeria.[2]

If the plot is in many respects banal, the style reflects what half a continent away in Soviet Russia Lev Kuleshov had already humorously diagnosed as a contagious artistic disease: “Americanitis.” Like his Russian counterpart and many other younger European filmmakers, Renoir professed to be fed up with the state of contemporary mainstream cinema. Directors in France had failed, he believed, to take advantage of the unique capabilities of the film medium. Many of their works were little more than recorded theater in which actors gesticulated silently with lengthy intertitles intervening to explain what they were saying. They were boring and uncinematic.

By contrast, American directors were developing new techniques to engage audiences; they reduced dialogue and more precisely conveyed the story in visual terms by gauging the distance, angle and lighting of the performers’ movements, facial expressions, and so on. They further anchored the dramatic action by carefully articulating the characters’ points of view and their reactions. I have already mentioned the Griffithian editing of the rape scene which weaves into the establishing shots looming close-ups and cutaways to dogs barking and a ticking clock to create suspense; each shot is carefully calibrated to produce a shocking, rhythmically alive event on screen. More than that: Renoir was also already thinking about how individual scenes fit into the entire film’s visual architecture. For example, he uses scenes set in bright sunlight followed by dramatically lit episodes at night to convey the shifting rhythm of Virginia’s fate from happiness to violence and back again. These are most striking early on when her simple, happy life with her father on the barge or with her gypsy friend is disrupted by harrowing nocturnal scenes: when boatmen dredge to recover her father’s body or when the mob wreaks its vengeance on the gypsies’ caravan. In such scenes, there is also a quasi-documentary impulse at work. Choosing to film on location which made lighting difficult to manage reflects strategies strenuously advocated by the famous naturalist theater and film director, André Antoine.

But Renoir was also enthusiastic about montage experiments even more radical than those developed in America. He often told a story about how he decided to become a filmmaker after seeing Le Brasier Ardent (The Blazing Inferno; released in France on November 2, 1923) directed by the émigré Russian actor, Ivan Mozhoukine. Like several French filmmakers of the period, including Jean Epstein, René Clair, and Abel Gance, Mozhoukine explored some of the new techniques they championed: poetic visual superimpositions, negative imagery, overexposure, shaky or rapid camera movements, and reversed, slow, or accelerated motion, all dynamized by rapid changes of the images. In prominent articles in the intellectual and film press of the time, these directors defended such techniques as essential novel contributions the cinema had made to the visual arts. Certainly, Renoir’s most innovative experiment in this vein is the pièce de résistance of Virginia’s delirious dream articulated by almost the entire range of new cinematic techniques he prized. Indeed, Jean Tedesco, the enterprising avant-garde cinema impresario who owned the Vieux Colombier movie theater, thought so highly of the sequence that he excerpted it and presented it with others to represent the best of innovative modernist cinema.

Renoir’s friend and screenwriter, Pierre Lestringuez, as Virginia’s dissolute Uncle Jeff.

To be sure, La Fille de l’eau’s heady, eclectic synthesis of stylistic initiatives was the work of a novice who wore his influences on his sleeve. But—pace Bazin—this in no way discounts the interest and quality of precisely the scenes that Renoir’s fledgling skills and ambitions animated with great verve. Nor should Bazin have singled out Hessling, Renoir’s first wife whom he chose to play Virginia, as the one responsible for having “slowed [Renoir’s] passage from the simple photographing of actors to true movie making.” At the time, more or less self-taught as an actress, Hessling is quite self-assured and surprisingly comfortable in her role as an innocent ingenue. (The English distributors clearly understood the nature of the part by renaming her Virginia.) Her performance is very much of a piece with the dominant American acting styles of the period. She channels the Gish sisters or Mary Pickford, and, in a nice touch, she even throws in a few allusions to Chaplin’s comic, mechanical dexterity—watch how she nonchalantly flips the plates she is washing; it is a kind of in-joke homage avant la lettre later indulged in by New Wave filmmakers. The other amateur actors, including Lestringuez and Justin Crépoix, or the painter André Derain in his bit part as a bartender, do not have the same acting chops as Hessling. That Bazin blamed her was simply unfair, a perverse spin on cherchez la femme.

If La fille’s plot was a melodramatic song of innocence redeemed, the story of Nana was the reverse: a cautionary tale of decadence damned. Zola had invented as the central character of his novel a demonic femme fatale, the eponymous Nana, a would-be actress and—to put it quite delicately—a courtesan to incarnate the evil of contemporary society. Zola attributed her malevolent force to the hereditary consequences of alcoholism, the central theme of the entire famous Rougon-Macquart series, and resisted any probing of her psychology. Like Zola, Renoir and Lestringuez resisted establishing motives for Nana’s outlandish behavior in past trauma or social poverty. They simply let her behavior establish her character by presenting scenes of her heavy drinking, as well as her carousing, tantrums, wasteful extravagances, and domineering humiliation of the men who abandoned all restraints to throw themselves at her feet. No doubt such scenes offered far more salacious spectacles for an audience to enjoy. Both for reasons of propriety and commercial viability, however, their adaptation had to reduce the novel’s scope. Eliminated were the novel’s raunchiest parts and many plot digressions, leaving only hints of Nana’s willingness to prostitute herself, her open bisexuality, and the endless string of paramours whose lives she ruined. Commercial interests intervened as well: the cuts were necessary in order both to avoid censorship as well as to ensure that the film remained at a commercially exploitable length.

Hessling as Nana.

We meet Nana (Catherine Hessling) in an especially striking opening scene as the star of “The Blonde Venus,” a popular spectacle that was all the rage in Paris. A slow crane shot rises with her as she climbs a ladder up to the theater rafters; the shot is capped by a virtually vertical close-up take of her frizzy hair with the waiting cast on the stage down below. Tied to a rope, she is then slowly lowered by a stagehand into the center of groups of extras dressed in mock-Roman garb who await her descent. All the swells and plebes, men and women (but especially the men) in attendance, primed by this coup de théàtre are eager to see the new sensation. In the audience are the cynical Count Vandeuvres (Jean Angelo), his naive nephew Georges Hugon (Raymond Guérin-Catelain) and the straitlaced, awkward Count Muffat (Werner Krauss). As Nana descends from on high, a kink in the rope stops her in midair; she dangles, helplessly flailing in the air. The comic note, which so amuses the poorer patrons in the upper galleries, however, in no way cancels the allure of her sex appeal for the three upper-class men. Spoiler alert: That appeal spells their doom; before the film’s end, all will fall victim to their lust for this man-eating creature.

After her subsequent failure to succeed as a legitimate dramatic actress, Nana uses a barely concealed promesse de bonheur to persuade her suitors to do her favors and buy things she wants. The first to deliver himself into her clutches is Muffat who abandons his wife in their box seats so that the play’s slimy producer (Pierre Lestringuez) can help him gain entry into Nana’s dressing room. Nana pops up from behind a screen, presumably naked, to greet him. He is smitten. When she asks for her comb, Muffat quickly spies the filthy object and brings it to her, much to the astonishment of her hairdresser (Harbacher) and servant (Valeska Gert). His eyes downcast, he humbly offers it to her, but not before removing the hair stuck in its remaining tines, a not so masked suggestion that the hair will become a fetish. In another, later nod to the darker side of male sexuality, Hugon will excitedly arrange one of Nana’s dresses on a chair as a substitute for the Nana he desires when she was working to seduce his uncle in the next room. Renoir’s openness to introduce, even if obliquely, the more degraded dimensions of social and psychological life while toying with quasi-psychoanalytic insights was also inspired by an American filmmaker, albeit one who made films quite different from Griffith’s muscular editing style. Renoir admitted having seen Stroheim’s Foolish Wives (1922) no less than ten times when it was released in France. Its plot about an attempted seduction as well as Stroheim’s inclusion of various sordid details clearly appealed to him and encouraged him to make even bolder innuendos in Nana. Such scenes reach their apogee when Nana forces Muffat into masochistic submission by making him crawl on all fours and bark like a dog. Even Stroheim might have blushed and then hesitated at putting such a daring topic so nakedly on screen.

Jean Angelo and Hessling as Nana and Count Vandeuvres.

Hessling is at the center of virtually every scene in the film. Her performance is one of the most singular and strange in all of silent cinema. Bazin’s description of Hessling as “a curious creature, at once mechanical and living, ethereal and sensuous” is spot on, but he somehow failed to recognize that these qualities quite perfectly suited her for the role’s emotional vicissitudes. She is often presented as an impulsive child who acts out her whims while remaining slithery and seductive. Covered by thick white makeup and darkly circled eyes, her face becomes a mask.[3] Her emotional expressions are conjugated through an assortment of grimaces, smirks, and pouts; her eyes widen and narrow in response to anger or when sensing opportunity. This characterization—which Renoir and Hessling apparently developed together—and her actualization of it lies at the farthest possible remove from the kind of naturalistic performance style Hessling had attempted in La Fille. Its roots clearly harken back to roots in Frank Wedekind’s early “Lulu” plays and other Expressionist works—a characterization not lost on early French viewers who condemned the film (whose interiors were largely shot in Berlin) as “Boche” (German). It certainly lies far outside the acting canon that Bazin endorsed, but it has its own integrity and cannot be so easily invalidated.

Nana is the first of several subsequent Renoir films either to be set in a theatrical milieu or that invoke theater as a metaphor for the follies and pleasures of contemporary social life. Here the world of make-believe, spectacle, and illusion takes on a bitter, ironic edge. Anticipating some of his later masterpieces such as Grand Illusion (1937) and above all The Rules of the Game (1939), Renoir contrasts Nana’s intoxicating whirl and opulent lifestyle of elites at the top of the social ladder with several instructive, if brief, moments in the lives of her servants and theatrical colleagues. Her impecunious fellow actors compete with her for roles but remain loyal out of envy and admiration for her extraordinary material success. The servants generally submit to her whims, but they also mock their mistress behind her back. A rather shocked Muffat gets to know them when he attends two raucous dinner parties, one for the actors at the beginning and the other for the servants at the film’s end. In both, the actors and house staff gorge themselves at Nana’s expense, bicker and some even engage openly in erotic shenanigans. Ultimately, the upstairs–downstairs theme culminates when the servants’ venal instincts are unleashed as Nana’s fortunes begin to falter. They throw off the hated livery they wore and steal her blind before abandoning her for good. It is a denouement that Bunuel would certainly have appreciated and later elaborated in even coarser terms in Viridiana (1959).

As Noël Burch pointed out many decades ago in Praxis du cinema (1969) [the English translation, Theory of Film Practice, was published in 1981 by Princeton University Press], Nana also continues Renoir’s exploration of the medium, pushing new boundaries in the way cinematic space is articulated. The mise en scène of many scenes, especially of those set in the theater or in the mansion Nana lives in, tends to align actors horizontally across the picture plane. But Renoir crucially articulates the many ways in which they move into or exit the frame—from or to left or right? top or bottom? toward or away from the camera?—as well as how the camera’s movement can sweep back from a fairly close position to open up and dynamize the playing space. Even if Burch’s characterization of these formal relations as a “dialectic” is an overstatement, Bazin’s carping about a supposed lack of logic of Renoir’s editing is put into perspective or in some sense is beside the point. Renoir’s searching mind was experimenting with other perceptual dynamics of the medium for sophisticated viewers then and still today.

Nana and Count Muffat (Werner Krauss).

The restored versions of these two films join many heretofore largely inaccessible titles that have been reissued on DVD and Blu-Ray over the last few years. Restorations, however, come in many forms. Some simply use new technologies to refurbish the best existing print the technicians and distributors can access. Other restorers do more thorough research. They hunt through film archives across the world (and sometimes in flea markets and amateur collections, too) for missing shots and then incorporate them with the help of existing scenarios, reviews, etc. to create an expanded film greater than any existing print before turning over the newly created version to technicians to remove scratches and improve tonal contrasts in the images. (Such was the case with the Austrian Film Archive’s recent release of The City without Jews (1924) or Kevin Brownlow’s historic reconstruction of Abel Gance’s Napoleon (1927). Whatever the case may be, however, virtually all restorations are at most approximations of an original and not its reconstitution. Versions that omit shots or scenes subtly alter how we interpret the film. Others that restore color toning of scenes that were especially important for more ambitious projects do so in the name of authenticity or enhancing viewers’ pleasure in watching. And restorations rarely include the musical score that audiences heard at their premieres but instead commission contemporary scores to cover the disconcerting silence of old movies.

I wonder, in fact, what version of these films did Bazin see? Did the prints he could access in some way lead him to underestimate these films? In the filmography of the Renoir book, for example, the listing for La Fille de l’eau cites its duration as seventy minutes. Curiously, a half-century ago, the English film critic Raymond Durgnat reported that Cahiers du cinéma claimed the French had to make do with a version of La fille based on the English release of the film that was more than ten percent shorter (approximately eighty-nine minutes) than the only supposedly full-length, one-hundred-minute version deposited solely in the Moscow film archive. The confusion deepens in a prefatory title of the Kino Lorber edition produced by Studio Canal in France, announces at the beginning that all the elements of the film were preserved at La Cinémathèque française and it lasts just eighty-three minutes, which is certainly better than the sixty-eight-minute copy recently screened at the Cannes Film Festival but still leaves me in the dark about what Bazin might not have been able to see. In any case, the Kino Lorber version under review is clearer and cleaner than an older print I saw years ago and is certainly a welcome addition to the Renoir canon.

If anything, the new restoration of Nana is even more puzzling. The one extra feature on the Kino Lorber disc shows the care with which its restorers have removed scratches and blotches as well as brightened and clarified the contrast of the gray tones to vastly improve the visual quality of the black and white images. On the other hand, a restored version of the film produced for Arte Video by the respected firm L’Immagine Ritrovata from seventeen years ago added toning to many of the scenes in yellow, orange, and lavender while leaving other images in black and white. Presumably, the restorers had knowledge that this is the way the film appeared in its original state, though the underlying images seem slightly less clear. But if toning was used, why is such a feature absent from the Kino Lorber version?

There are other significant differences, too. The Arte version clocks in at two hours, seventeen minutes, which is about thirty minutes shorter than the Kino Lorber edition. We know that Renoir reluctantly reduced the running time of Nana after its premiere before it went into its initial public release. If the aim of the Kino edition is to recreate the longer, original director’s cut, that would be admirable. But is that really what they offer? The extras provided in the Arte package include an excerpt from “Jean Renoir, Le Patron,” an interview filmed by Jacques Rivette for the Cinéastes de notre temps TV program in the mid-1960s. In a few excerpts, no less than five shots and five intertitles, all from the opening scene in the theater, appear. These images were clearly available but, inexplicably, they were not used in either of these versions. The same is true of shots used to mark the chapter headings in the 2004 edition, which also includes an alternatively edited ending as an extra supplement. But once again, none of these were chosen for inclusion that also do not appear in both restorations. Why not?

Some of the confusion might have been cleared up by comments added to the one brief clip Kino Lorber provides to illustrate how the images of their version have improved its legibility. They do not. True, this firm’s releases tend to be rather austere and limited. They do not print fancy booklets with probing essays and stills as, say, The Criterion Collection does. Neither of the releases under review provides even a single sheet with lists of the cast and production crews.

What they offer instead, however, are optional voice-over soundtracks with comments by film historians or critics who fill in the background of the film’s production; provide information about the way the film was adapted from literary sources; offer intriguing biographical details about both major and minor actors and the production team; and highlight pertinent stylistic features. In both these releases, Nick Pinkerton, who had already provided such a narration for Renoir’s La Marseillaise (1937), mines many useful details from Pascal Mérigeau’s copious 2012 biography of Renoir and generously cites other critics’ appreciations of the films and their place in the director’s oeuvre. At moments, the information he provides is very dense, but he is a sure instructive guide into the films’ many complexities that are worth listening to more than once.

Stuart Liebman is professor emeritus of film studies at Queens College and the CUNY Graduate Center and a Contributing Writer for Cineaste.

[1] Later in his career, the overly modest Renoir admitted that the silent films were useful to him because they served as his introduction to cinematic technology and techniques. As for his failures to constrain performers, Renoir’s personal rancor toward his first wife, Catherine Hessling, the star of the first two features as well as several shorts he directed, remained a sore point in his life. The divorce proceedings that she protracted for a dozen years may have made him more sympathetic to Bazin’s claim that she “slowed his passage from the simple photographing of actors to true movie making.”

[2] Renoir’s tolerance for the French colonial project in North Africa does not bespeak a high degree of his political consciousness at the time.

[3] Shooting with orthochromatic film further heightened the contrast.

Copyright © 2021 by Cineaste Magazine

Cineaste, Vol. XLVII, No. 1