Mirror (Web Exclusive)

Reviewed by David Sterritt

Produced by Erik Waisberg; directed by Andrei Tarkovsky; screenplay by Alexander Misharin and Andrei Tarkovsky; cinematography by Georgy Rerberg; art direction by Nikolai Dvigubsky; music by Eduard Artemyev; edited by Lyudmila Feyginova; starring Margarita Terekhova, Ignat Daniltsev, Larisa Tarkovskaya, Alla Demidova, Anatoly Solonitsyn, Nikolai Grinko, Tamara Ogorodnikova, Yuri Nazarov, Oleg Yankovsky, Filipp Yankovsky, Yuri Sventikov, Tatiana Reshetnikova, and Innokenti Smoktunovsky. Blu-ray and DVD, color and B&W, Russian dialogue with English subtitles, 106 min., 1975. A Criterion Collection release.

Andrei Tarkovsky’s semiautobiographical Mirror reached American theaters in 1983, eight years after its extremely limited release in the Soviet Union, and on first viewing I found it all the things the publicity for the new Criterion Collection edition says it is: poetic, richly textured, mystical, and above all elusive, as intense yet ungraspable as a multilayered dream. Seeing it again, though, I was surprised by how lucid, coherent, and articulate it had come to seem, even though I hadn’t done any deep thinking or studying up in the interim. It’s a profoundly personal and radically nonlinear film, to be sure, but its mercurial structure has an intrinsic logic and its images and sounds are as enchantingly beautiful as they are meticulously crafted. I have spent many hours with it over the years, and I’ve spent a few more with Criterion’s fine digital transfer and extensive extras package, and today I find the movie less mystifying but more mysterious than ever—less mystifying because familiarity makes its codes easier to crack, more mysterious because what underlies the codes is a sense of reality rooted in metaphysical enigma rather than everyday rationality. Tarkovsky was a bold and innovative stylist, moreover, pioneering and exemplifying the so-called slow cinema espoused by such deliberative directors as Lav Diaz, Béla Tarr, Tsai Ming-liang, and Alexander Sokurov, the chief inheritor of Tarkovsky’s legacy. Among its many other virtues, Mirror gives you time to contemplate its conundrums even as they’re unfolding on the screen.

Margarita Terekhova and Oleg Yankovsky as Natalya and Aleksei.

The title Mirror has multiple meanings, including the notion that culture and media reflect the inner lives of the artists who make use of them. Tarkovsky used them to explore his own psychological concerns, and, more important, to seek out the larger spiritual forces he regarded as the all-pervading matrix of human existence. Not even the forthrightly religious Andrei Rublev (1966) outdoes Mirror in exemplifying his belief that faith, salvation, redemption, and renewal are the most imperative subjects an artist can investigate. Although some critics with secular worldviews write off his interests as hazily “spiritual” rather than pointedly religious, Russian Orthodox Christianity informs every one of his major features, very much including Mirror, and the distaste this aroused in Soviet bureaucrats at the Mosfilm studio was a chief cause of his emigration to Italy after filming his 1983 masterpiece Nostalghia there. Mirror doesn’t dwell on the traditional iconography celebrated in Andrei Rublev, and its elliptical narrative, grounded in Tarkovsky’s own memories, dreams, and experiences, is less otherworldly than the stories of Solaris (1972) and Stalker (1979), the science-fiction epics made just before and after it. But no film better embodies his conviction that cinema is the best possible medium for connecting ordinary mortals with an awareness of the invisible sublime. Many of its perplexities stem from his refusal of taken-for-granted boundaries that lend order to our thinking but reduce its nuance and complexity; as film scholar Nariman Skakov showed in his 2012 book on Tarkovsky’s work (The Cinema of Andrei Tarkovsky: Labyrinths of Space and Time), Mirror blurs countless borders between past and present, fiction and documentary, private and public, and society and individuality, transforming the world into a numinous realm that exceeds and confounds the cause-and-effect continuity of conventional cinema. Hence his love for visual perspectives that defamiliarize places and personalities, incongruous cuts that scramble time and space, and lengthy takes that enable the “sculpting in time” at the heart of his practice.

Ignat Daniltsev as Aleksei’s son, Ignat.

Mirror begins with a scene that paradoxically combines documentary realism with dreamlike obscurity: a boy switches on a living-room television set, the TV image expands to fill the movie screen, and we see a woman in a clinical smock cure a young man of stuttering by means of hypnosis. Neither the hypnotist nor the patient is seen again, but the boy watching the TV turns out to be Ignat, the son of Alexei, the surrogate for Tarkovsky in the film. The opening titles follow, after which the main body of the narrative commences with a serendipitous meeting between a rural woman named Maroussia and a physician going someplace or other with his medical bag. As they part, the man glances back at his new acquaintance, and a sudden gust of wind rushes through the tall grass between them (a delicious effect facilitated by an off-camera helicopter) suggesting an ephemeral link between the two. Evidently suffering some deep sadness, the woman goes on to a string of activities that are both mundane and oddly cryptic, such as watching a barn burn down during a rain shower and washing her hair in a black-and-white interlude as ghostly and surreal as any J-horror imagery.

These sequences introduce one of the three levels of time that converge and diverge over the course of the movie. The first takes place in the years preceding World War II and centers largely on Maroussia (Margarita Terekhova), whose husband has run off and left her with their young children. The second transpires during the war, often revolving around the young Alexei, who converses with an unidentified and evanescent visitor, goes through some poorly implemented military training, visits a neighbor with his mother, and reunites with his father. In the third, set about twenty-five years later, the adult Alexei argues with his estranged wife, Natalie, about who will have custody of Ignat and moves toward his own death from an unspecified cause. The movie ends with Maroussia smiling through tears while seeing her children walk through the countryside with what appears to be a much older version of herself. These are only a few of the film’s incidents; others are dramatically emotional, as when Maroussia panics over a possible mistake in her work at a printing plant, and still others—easily the most memorable—are utterly oneiric, as when workers tend a massive hot-air balloon at some vertiginous height above the earth, or when Maroussia, after reluctantly agreeing to slaughter a neighbor’s rooster, inexplicably levitates and hovers in midair, as if the material world had relinquished its hold for reasons neither she nor we can ever understand. The film oscillates between color and black-and-white footage, most of it shot by the gifted and eccentric cinematographer Georgy Rerberg and some gleaned from vintage newsreels, such as an astonishing view of Soviet troops slogging across a lake in wartime, which Tarkovsky likened to the Exodus of Old Testament times.

Anatoly Solonitsyn and Terekhova in a mundane yet cryptic scene.

Along with its protean array of periods, settings, and characters, Mirror contains a tremendous wealth of allusions to works in other art forms; one needn’t be a certified art historian to enjoy its visual quotations from Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s “The Hunters in the Snow” (1565) or Johannes Vermeer’s “Girl with a Pearl Earring” (1665), or to ponder the references to Fyodor Dostoevsky and the Book of Revelation, or to appreciate the verses recited on the soundtrack by Arseny Tarkovsky, the filmmaker’s father, a respected Russian journalist, translator, and poet (who once came perilously close to execution after dissing Lenin in some teenage doggerel). These are signs of the devotion Tarkovsky felt toward the likes of Johann Sebastian Bach, Leonardo da Vinci, Leo Tolstoy, Robert Bresson, and, perhaps above all, William Shakespeare, whose Hamlet was “clearly the most important and poetic work ever created,” as Tarkovsky opines in the documentary Andrei Tarkovsky: A Cinema Prayer, directed by his son, Andrey A. Tarkovsky, and included in the Criterion edition. In that film Tarkovsky describes the giants he most admires as “holy fools” and “lunatics” who didn’t “belong to this world” and were “possessed” by their art. “People like that frighten me and at the same time inspire me,” he says. “Their work is absolutely impossible to explain…Miracles can’t be explained. A miracle is God.” Beyond signaling his reverence for these figures, Tarkovsky’s allusions indicate his belief that while cinema is the newest and youngest art, it can summon unconscious resonances in viewers’ minds by incorporating materials from bygone eras in every other art. This point is made in two other Criterion extras, a British documentary called The Dream in the “Mirror” (2021) by Louise Milne and Seán Martin and a video interview with Eduard Artemyev, the film’s composer. Not that Artemyev exactly composed the score. As he says in his interview, Tarkovsky told him he he didn’t need a composer since he had Bach at his disposal, so Artemyev’s job would be creating sounds that could serve as subliminal characters in the film. Artemyev did just that, and his explanations and descriptions on the Criterion disc opened my ears to dimensions of the soundtrack I’d never perceived before.

A scene that alludes to Pieter Bruegel’s Hunters in the Snow.

Other extras in the Criterion edition include brief TV interviews with Tarkovsky, a TV documentary about Rerberg, and a video interview with Alexander Misharin, who co-wrote the film, along with a preliminary treatment and early draft of the screenplay (when “Confession” and then “A White, White Day” were the working titles) in a nicely illustrated booklet. With ancillary aids like these now available, Mirror should find a wider audience—and a more informed and comprehending audience—than ever before. Its reputation as an exercise in incorrigible puzzlement has surely dissuaded many people from engaging with it, and it’s a little comforting to know that making it was hugely puzzling for Tarkovsky, who struggled mightily with the editing and often feared it would never come coherently together. In the end, he succeeded so well that Mirror stands up brilliantly not only as a discrete work but also as a thematic capstone to the string of masterpieces he created in the Sixties and early Seventies. He says in A Cinema Prayer that Mirror, the relatively straightforward wartime story Ivan’s Childhood (1962), the period epic Andrei Rublev, and the science-fiction drama Solaris all partake of his “desire to develop and delve into characters who exist in a state of extreme tension, who are going through an intense spiritual crisis in which they must either break down or finally get their footing…in terms of being faithful to their ideals and true to their principles.” Rudimentary though that formulation is, it offers a helpful clue to what this complex and introspective artist saw as a basic tenet of a key period in his career.

Soviet authorities hated Mirror, restricting its release to a small handful of out-of-the-way Russian theaters, and Soviet critics lambasted it. But what mattered to Tarkovsky were the letters he received from everyday moviegoers who felt personally touched and intimately understood by a filmmaker they’d never met. In the documentary by his son, he quotes a remark made by a cleaning woman during an audience debate after a screening: “The film is very clear [and] very simple,” she said. “A man fell very ill and thought he might die. He remembered all the terrible things he’d done to others and wanted to apologize. That’s all.” To which Tarkovsky adds, “The many film critics present hadn’t understood a thing, as usual. The more they talk, the less they understand. And that simple woman explained it all.”

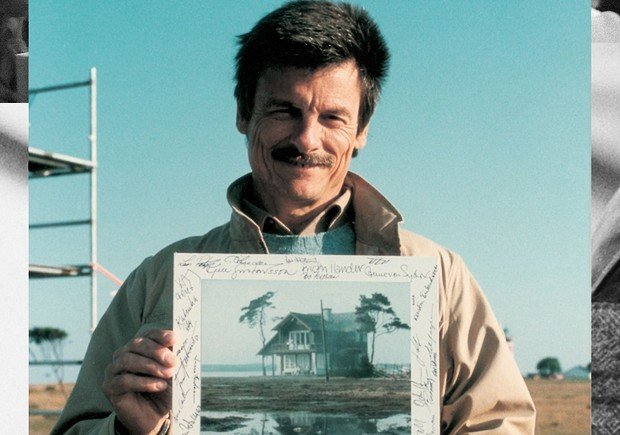

Andrei Tarkovsky in his son, Andrey’s, documentary, Andrei Tarkovsky: A Cinema Prayer.

I wouldn’t take that anecdote too literally; no matter how you slice it, Mirror is a knotty, gnarly film, and while a naïve viewer with fresh eyes may well have interesting ideas to offer, there’s obviously more to it than the meandering regrets of a repentant sinner on his sickbed. To make a broad generalization about my own relationship with it, I find Mirror as challenging and invigorating as various other high-modernist and postmodernist works I’ve thought of during recent viewings, such as James Joyce’s Ulysses and Finnegans Wake, Arnold Schoenberg’s Moses und Aron, and Stan Brakhage’s Sincerity/Duplicity (1973–80) series. These achievements, like Tarkovsky’s, tantalize the mind as much as they beguile it. Fathoming the depths of Mirror is a labor of love and an unending pleasure. Cinephiles can warmly welcome the new Criterion edition for its technical excellence, its generous array of additional resources, and the encouragement it offers for diving ever deeper into a unique and extraordinary film.

David Sterritt is editor-in-chief of Quarterly Review of Film and Video, film professor at the Maryland Institute College of Art, and author or editor of fifteen film-related books.

Copyright © 2021 by Cineaste Magazine

Cineaste, Vol. XLVII, No. 1