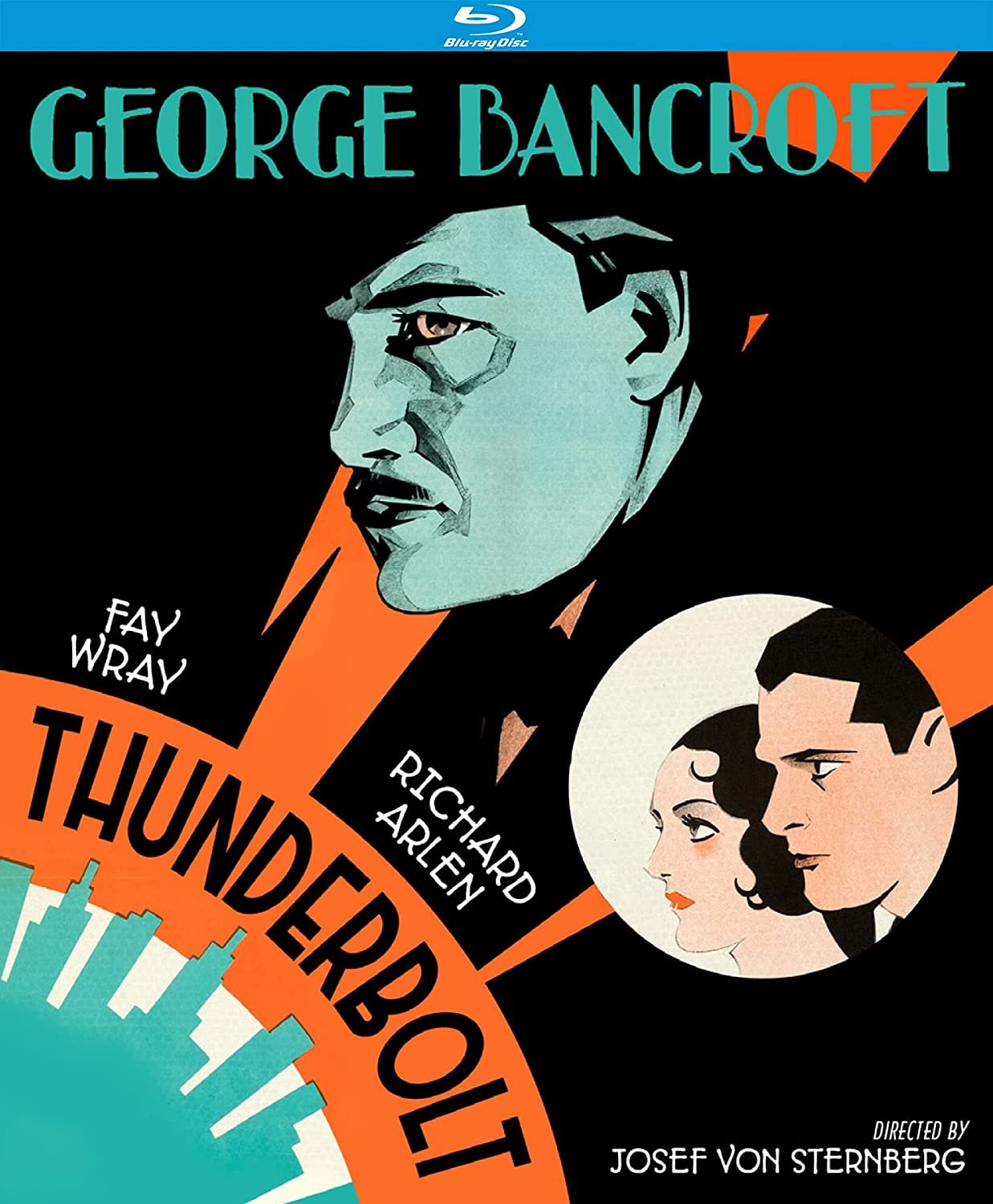

Thunderbolt (Web Exclusive)

Reviewed by Catherine Russell

Thunderbolt is a gangster played by George Bancroft who carries a name that sounds as big as he is. He has a reputation to match, but the film of the same name ironically works to undercut his menace and make him tame. Thunderbolt goes to his death in the end as a man with a big heart and a large laugh, which is the biggest sound that he makes in the entire film. Von Sternberg’s gangster film is the first he made using sound, experimenting with off-screen dialogue and music to great effect, and he makes a special splash in the first fifteen minutes. In a mixed-race club called the Black Cat Café, Theresa Harris bursts onto the scene in a sequined dress and a big smile. She sings “Daddy Won’t you Please Come Home” with vigor, backed up by Mosby’s Blues Blowers, while Thunderbolt and his girl Ritzy (Fay Wray) talk at a café table. As they retreat to a private room, Thunderbolt sneaks a peak at Harris before closing the door. Cut back to Harris on stage, and then, when Sternberg cuts to the interior of the private room, the sound is abruptly cut off.

In 1929, background music had to be played live during the shooting, and von Sternberg takes this as a creative challenge. The setting of the Harlem jazz club introduces the musical underscoring of the film, which is discontinuous and always linked to diegetic sources. Harris appears only in this scene, which marks her first screen appearance, inaugurating a thirty-year career in which she was ever after systematically assigned to the role of maid. In Thunderbolt we see the promise that the young Black actor held, and the future that was denied to “Hollywood’s longest serving maid.” Other actors in the Black Cat Café scene include Louise Beavers and Oscar Smith, two more busy Black actors of the classical era. Sternberg uses many bit players, both Black and white, to create a lively underworld community of dynamic characters. Most of the second half of the film is set in death row where Thunderbolt ponders his life as a brute, and even though the transition from the Black Cat Café to the prison is not direct, echoes of the former infect the latter, particularly through the African American spirituals on the soundtrack.

George Bancroft as Thunderbolt and Fay Wray as Ritzy.

The Black Cat Café scene ends with a police raid, but leading up to the raid, as Thunderbolt and Ritzy return to their table, the band sounds like an orchestra warming up, with stray trumpet lines escaping like free jazz. The lights go out, and Thunderbolt escapes, leaving Ritzy, who is more than ready to leave him and his underworld “show” for her childhood sweetheart, a young banker named Bob Moran (Richard Arlen). The cops follow Ritzy and eventually trap Thunderbolt in Moran’s apartment building where he has gone to kill his rival. He has already arranged to have Moran fired and concerted all his underworld power to make Moran’s life miserable, in the unrealistic hope of getting his girl back. Ritzy has told him in that soundproof room, in no uncertain terms, that he does not own her. Even so, after his arrest, Thunderbolt has his henchmen frame Moran for a bank robbery, and he ends up across the hall from Thunderbolt on death row.

Inside the prison, the inmates are mostly separated from each other visually, but they can communicate through words and song. One Black prisoner, played by S. S. Stewart, is allowed out of his cell to play piano for the men. First up on his playlist is the gospel song “Roll, Jordan, Roll.” When he first arrives, Thunderbolt is asked by one of the off-screen inmates if he can sing tenor, to which the tough guy responds, No. I kill tenors.” Soon enough though, an a capella quartet can be heard off screen, singing what came to be known as “barbershop” music, although many of the songs in this film sound more like African American gospel, which was an important antecedent to white barbershop music. The Prison Warden (Tully Marshall) says he keeps trying to break up the group, but more singers keep being sent down to keep the music going, although no singers are ever on camera.

While contemporary viewers may well see the appropriation of African American music for the redemption of white men, in 1929 it was a novel means of integrating Black culture into an otherwise very white movie. The singers are not only unseen but they are also uncredited, but the soulful music, some of it written by white composer Sam Coslow, may well have been led by the piano player S. S. Stewart, for whom this is his only screen credit (according to IMDb). Sternberg’s orchestration of the dialogue overlapping the music—which would have been played and sung on the soundstage—is not only technically impressive, but it creates a unique atmosphere for death row.

Thunderbolt and Bob Moran (Richard Arlen) face off in the big house.

The unseen singers are briefly replaced by a white instrumental ensemble who accompany the film’s romantic scenes with waltzes and romantic string music. Five men carrying instruments walk nonchalantly into the prison behind some foreground action concerning Thunderbolt and the Warden. One prisoner complains that they keep playing the same song over and over. In any case, after Nolan and Ritzy (now called Mary) get married in the jail and Thunderbolt admits to having framed Nolan (his wedding present to his ex), one of the prisoners yells, “A little music, Professor?!” and the a capella group launch into a new song.

Harlem jazz club, The Black Cat Café.

Thunderbolt’s tough-guy stance is modulated by his generous gift to his ex and the innocent man that she loves, but his transformation is heralded—if not caused—by a stray dog that takes a liking to him. By following him into Moran’s building, and not backing down despite Bancroft’s silly dog-mimicking antics, the mutt and his bark attract the police, leading to Thunderbolt’s arrest. Eventually, at Thunderbolt’s request, the Warden allows the dog to share Thunderbolt’s cell. A black cat also features in the opening scene, leading up to the Black Cat Café, and a cat face returns in the form of a plastic dog toy that Thunderbolt squeezes and squeaks with his powerful fist as his final hour approaches. Sternberg manages to weigh the animals’ sentimentality against Bancroft’s bulky strength, rendering their symbolic fatalism curiously domestic and mundane.

Theresa Harris singing “Daddy, Won’t You Please Come Home.”

Thunderbolt garnered mixed reviews in 1929, with the inimitable Mordaunt Hall of The New York Times complaining that it was not an “edifying” picture, especially since Bancroft’s Thunderbolt laughs hysterically on his way to the chair. Indeed, the film’s novelty was precisely in the way that the vicious gangster is rendered humane. Mind you, we don’t witness any atrocities by his hand, as the only crime he is seen to commit is having Moran framed. Variety described the film as “routine” and, indeed, many of the themes of Sternberg’s 1927 Underworld are revived here, including Bancroft in the starring role and the love triangle that trips him up. The addition of sound, however, not only enabled Sternberg to add a delicate, selective, and inventive soundtrack, but the witty, wisecracking, gangster slang makes the film an important early contribution to the genre. Some of the wisecracks even allude to the racial composition of the death row inmates when Prisoner #7 (Stewart) mutters to a guard, “I wish there was a way of telling when a human being was out of tune.”

Nick Paumgarten’s commentary on the new Kino Lorber release fills in a great deal of detail about the bit players, who are responsible for much of the smart-talking banter. All the prisoners on death row get little monologues and even snatches of song, often commenting on Thunderbolt’s plight and the new arrival Moran. Paumgarten’s account helps to underline the critical contribution of long-time bit players such as Ed Brady, former baseball player Mike Donlin, and Fred Kohler, not to mention Beavers, Smith, and Harris who appear in the Harlem club scene. The dark-shadowed low-key lighting of Thunderbolt’s cinematography (credited to Henry Girard), which utilizes the bars of the prison cells to cast atmospheric shadows over and behind the prisoners and their various visitors, looks fantastic in this restoration of a film that has long been missing from the archive of early sound films.

Catherine Russell is Distinguished Professor of Film Studies at the Mel Hoppenheim School of Cinema at Concordia University in Montreal and author of several books, most recently Archiveology: Walter Benjamin and Archival Film Practices.

Copyright © 2021 by Cineaste Magazine

Cineaste, Vol. XLVII, No. 1