Warren Beatty, Reds, and I (Preview)

by Robert A. Rosenstone

The beginning of this story could be right out of a 1940s film noir. An unexpected phone call sets in motion a series of events that will significantly change the focus of my career and alter the path of my life. If I cannot be precise about the date, I well remember the scene. 1972. A late fall after-noon a few months after my return from a research trip to the Soviet Union. I am staring at a blank sheet of paper in my Olivetti portable typewriter set on a door held up by two sawhorses in my apartment on Alta Vista, a street boasting a row of lofty palms close to the center of Hollywood, south of Sunset Boulevard, and three blocks west of Charlie Chaplin’s old studio on La Brea.

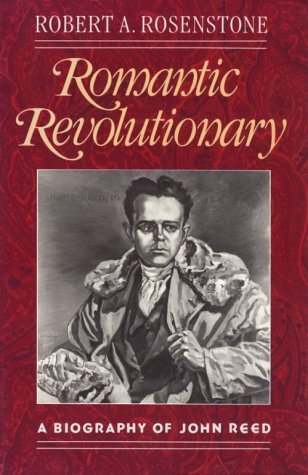

I am some two hundred pages into the first draft of what will become Romantic Revolutionary, a biography of John Reed, a once-famous early twentieth-century journalist and radical who was remembered in 1970s America only by old leftists or those who had taken courses dealing with the Soviet Union. When people at dinners or parties pose the question that writers hate—“What are you working on now?”—I am so fed up with explaining who Reed was and what he did that I have taken to giving a simple answer: “A book about the Russian Revolution.” Such questions underscore how far I am from that grassy embankment in front of the Kremlin wall where three months earlier I stood looking at Reed’s grave, as almost every Russian who filed by spoke his name aloud in reverential tones. Men took off their caps while looking at the name in Cyrillic letters on a bronze plaque set into a gray stone. One elderly woman kneeled and crossed herself.

I pick up the phone.

“Professor Rosenstone? Warren Beatty. I’m about to make a film on John Reed. At Harvard they told me that you’re writing his biography. We must talk. Dinner tonight? Tell me where you live. I’ll pick you up in an hour.”

Beatty, who was once no more than one of Hollywood’s beautiful faces, had become a megastar after the 1967 film Bonnie and Clyde, with its outrageous mixture of jaunty humor and graphic violence, was nominated for ten Oscars. A year prior to the phone call, he had starred in a Robert Altman production, McCabe and Mrs. Miller, one of the rare Hollywood products to excite my historical imagination. A kind of anti-Western that used a brothel as a metaphor for business large and small, the film presented perhaps the sharpest critique of predatory capitalism to come out of Hollywood since the Thirties. It even included a personal bonus for me as biographer: the bad guys are lumber barons of the Pacific Northwest who crush the claims of small loggers, the very men who John Reed’s father had, as a progressive U.S. Marshal, helped to prosecute for land fraud early in the twentieth century.

Warren Beatty as John McCabe in McCabe and Mrs. Miller.

More than fifty years later, I can’t remember my thoughts between the phone call and Beatty’s arrival. But they must have had to do with the mystique of Hollywood, my hometown since the age of ten. During my teen years, I loved movies. But, under the influence of an artistic mother and intellectual older brother, I no longer had a taste for the trivial productions that, for the most part, Hollywood then turned out, particularly the kind of soppy melodramas in which Beatty starred early in his career—The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone or Splendor in the Grass (both 1961). During my years at UCLA in the 1950s, as Arts Editor of the Daily Bruin, I came to enjoy works less formulaic and more artistic than the normal Hollywood offerings, films that exhibited some sort of social conscience or political resonance, like those turned out in the 1930s by Frank Capra or the works created in what was called The New Hollywood of the Sixties and Seventies, films that flaunted their antiwar themes or countercultural sensibilities—The Graduate (1967), Easy Rider (1969), Midnight Cowboy (1969), Alice’s Restaurant (1969), Little Big Man (1970), MASH (1970), The Last Picture Show (1971), Chinatown (1974), and Coming Home (1978).

I opened the door to see a tall man who was so handsome that it was difficult to look him directly in the face. His first words broke the spell: “Let’s trade John Reed fuck stories!”…

To read the complete review, click here so that you may order either a subscription to begin with our Winter 2021 issue, or order a copy of this issue.

Copyright © 2021 by Cineaste Magazine

Cineaste, Vol. XLVII, No. 1