When Documentaries Collide: How Should Nonfiction Stories Be Told (Web Exclusive)

by Matthew Hays

Filmmaking rivalries are not uncommon and often make for legendary stories. In a milieu where supply far outstrips demand, and where recognition is scant, it doesn’t take much to trigger epic resentment and bitterness.

Documentary history is itself rife with films and entire movements about resistance or reaction to previous cinematic movements or trends, created often for the burning need to be contentious. Traditional documentaries were often tied to propaganda—at times messaged via heavy-handed Voice of God narration—which invited contrary readings and subversive responses. Direct Cinema, Cinéma Vérité, and Great Britain’s Free Cinema movement were all responding (usually angrily) to the status quo, both in filmmaking and politics. These debates, screeds, and manifestos often involved discussions about who was being left out of the frame, which narratives were being focused on, and how.

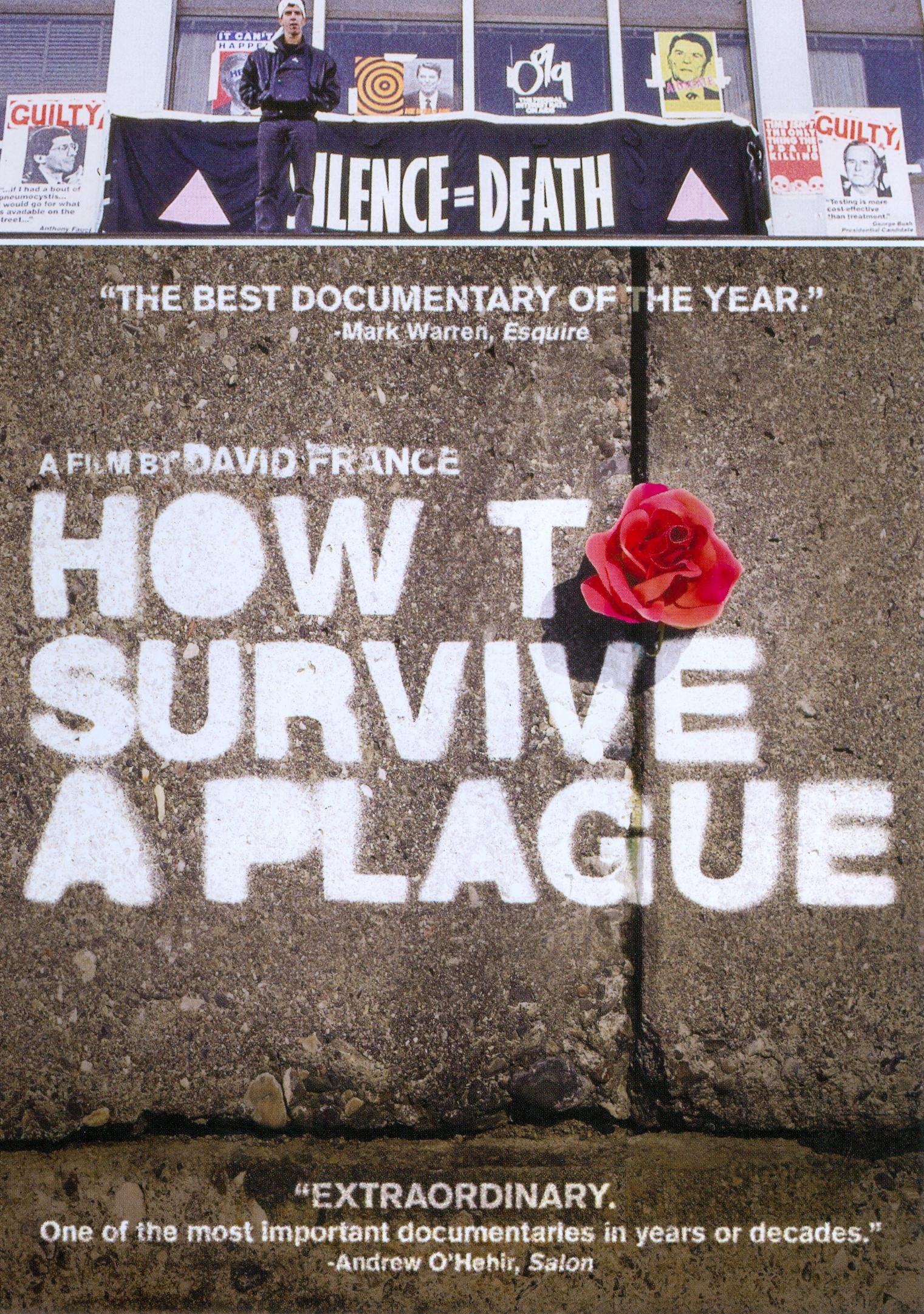

These fierce debates about how nonfiction stories are told, how history is shaped by documentary, which narratives should be privileged, and the political nature of their subjects, can be seen today in the distance between two 2012 documentaries about the same subject, How to Survive a Plague and United in Anger: A History of ACT UP.

Both films received critical accolades upon their release. Writing in The New York Times, Jeannette Catsoulis declared that United in Anger is “as scrappy as the actions it documents,” praising the film for capturing the anger and solidarity that infused meetings of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), a New York-born radical group formed in response to the pandemic, now widely regarded as a transformational movement in American activist history. The members interviewed, the reviewer concluded, were “Foot soldiers for the dying, [who]...never forgot how to live.”

Larry Kramer in United in Anger.

Writing in The Hollywood Reporter, David Rooney called How to Survive a Plague “emotionally charged,” noting that director David France’s strategy of shaping the archival footage with contemporary interviews means “the film deftly shapes its information stream into a powerful drama recounting the highs and lows, setbacks and victories in the fight for an effective HIV treatment.” Notably, Rooney also praised the film as “an epic celebration of heroism,” with France showing “a firm grasp of narrative, giving this decade-long chronicle a driving fluid through-line.” Noting that activist Peter Staley, a handsome, photogenic former bond trader who was radicalized by his HIV diagnosis, takes center stage, Rooney correctly identified the film’s appeal: “These individual stories stitched within a broad journalistic canvas are what make How to Survive a Plague such a rewarding experience and a vital testament to courage and endurance.”

At first glance, these two films could be interpreted as perfectly complementary. Directed by Jim Hubbard and co-produced by Hubbard and New York author Sarah Schulman, United in Anger relies heavily on the archival work the two had done together for their ACT UP Oral History Project, an online collection of interviews with group members. Hubbard adopts what could perhaps best be described as a mass protagonist approach, giving voice to a wide array of people who were involved with ACT UP’s direct action and media-attention-grabbing antics. By contrast, France chose to focus on the lives and actions of a few key activists, especially drawn to events that had been captured on video. Both films leave audiences deeply emotionally impacted; but one film reflects the idea that social movements are not driven by individuals, but by large groups of coalitions working together, while the other film highlights acts by individuals.

These differing approaches to documenting the history of ACT UP and HIV/AIDS is not something Schulman has taken lightly—she sees her collaboration with Hubbard as being an accurate reflection of the movement and disparages France’s approach. This has been a long-standing grievance, but proving that such sentiments die hard, the gulf between films/filmmakers has been granted fresh reminders with two new books that reflect on ACT UP New York’s storied history. Both Schulman’s Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987–1993 (Farrar, Straus and Giroux) and Peter Staley’s Never Silent: ACT UP and My Life in Activism (Chicago Review Press) were published last summer.

Almost a decade after the two documentaries were released, Schulman does not hold back in her grim assessment of France’s film; for her, this is something personal, as she explains that France relied on the online archival footage that Schulman and Hubbard had collected and created. “When it came to representing AIDS activism, among the many outcomes that we never predicted was that our open-source approach to making our interview footage and substantial archival footage accessible would get used to nefarious ends,” she writes in her preface. She goes on to charge that several films were made that used their material, but which were “not accurate.” She singles out France, arguing that How to Survive a Plague ”visually and formally argues for an understanding of AIDS activism through the heroic white male individual model, since he did subscribe to the four-to-six-characters prescription,” contrasting that take with Hubbard’s, which she praises as more faithful to reality: “[T]he success of the [ACT UP] movement was, by contrast, a consequence of the profound range of difference in the large group relationships that produced the AIDS coalition, reflecting our understanding that, in America, diverse grassroots movements for change must work together in order to be successful.”

Protestors in How to Survive a Plague.

Schulman continues, arguing that the very title of France’s film is “misleading and disturbing.” She points to the declarations of the AIDS crisis being over by some writers (most notably Andrew Sullivan, who wrote a New York Times Magazine cover story in 1996 titled “When Plagues End”) as being ludicrous, pointing out that for many (the poor and minority communities) the multiple crises around HIV/AIDS never ended.

“The mainstream approval France received for his film,” Schulman writes, “which relied heavily on footage others had archived, was depressing to us, not only because the impression it gives of how change is made and who makes it is false, but because the “heroic individuals” myth, aside from being inaccurate, could mislead contemporary activists away from the fact that—in America—political progress is won by coalitions.”

Without naming names, Staley directly addresses this strongly held disagreement between filmmakers in his book. He defends France and his vision in How to Survive a Plague, stating that “watching David blossom into one of the best documentarians of our era hasn’t surprised me at all...I’ve come to know the goodness of the man, even while critics have taken potshots at his work. I won’t give those critics space here, most because they always involve a competitive grievance disguised as contemporary identity politics. I remain in awe of his work and thankful for his friendship.”

In an email response to my query regarding this feud, France stated that, “Some people left those years with a bitter taste for the community. I came away with a feeling of pride in community and a bitter taste for the real criminals.”

Whether or not this rift is indeed a personal, competitive grievance or a different attitude towards how histories are told remains a point of debate. The two films do have creators in common: Hubbard directed United in Anger but also did crucial research for How to Survive a Plague for which he is credited as an associate producer. In his 2016 book How to Survive a Plague: The Story of How Activists and Scientists Tamed AIDS (Vintage Books), France mentions that he and Hubbard were briefly roommates in Manhattan during the outset of the AIDS crisis. (Hubbard did not respond to an email request for comment for this article.)

The Larger Debate: Against Story and Individual Heroes

Peter Staley in How to Survive a Plague.

But this clash over specific contrasts in styles points to a larger debate that is now engulfing those who are creating documentary films and TV projects.

Many documentarians are now responding to what some refer to as the tyranny of streaming services, meaning a conformity to a specific brand of nonfiction narrative. All documentaries, the formula goes, must find some kind of emotional human “in” to a story, favoring the four-to-six-person protagonists in How to Survive a Plague over the array of voices in United in Anger.

Writing in the Canadian documentary magazine POV as far back as 2013 (“Upping the Anti-: Documentary, capitalism and liberal consensus in an age of austerity,” POV, December 10/13), author Ezra Winton argued that while many if not most documentaries have a progressive veneer, not all were pushing back against the status quo to the same degree. “In fact, many documentaries trade on social justice and resistance themes while they deliver tepid political analysis, showcase mainstream perspectives, and call for resistance or reform,” wrote Winton. “The folks at Participant Media call this ‘social action entertainment.’ I call it liberal consensus documentary...And while I don’t discount the role centre-left media has to play in building a fair and just society... I’m concerned for documentary’s radical voices and their potential to be drowned out by the genre’s own mainstream glamour.”

Winton’s words have become prophetic. The market pressures have led some documentarians to respond in protest. In 2019, filmmakers Alexandra Juhasz and Alisa Lebow created a page dedicated to resisting the dominant strain of documentary storytelling, titled “Beyond Story: An Online, Community-based Manifesto.” (Volume 2, Article 3 at World Records Journal)

The authors begin with an earnest plea: “We need documentary,” they write, recounting that they met during the Eighties, when both were AIDS activist videomakers. “We use documentary. We use it as artists, as viewers and as activists to help us imagine new ways to engage with the world. We rely on documentary, in all of its eclectic variety, to record, trouble, explain, reveal, and share lived reality and our plans and hopes to transform it.”

Clearly recognizing the current trends in doc filmmaking, Juhasz and Lebow stress that one of the form’s key strengths is its very resistance to specific, generic forms: “We are drawn to documentary for its insurrectionary possibilities and its activist and engaged orientations. Just as—and because—we resist by using documentary, documentary resists generic and formal categorization. It must be adaptive to be most useful. And so, form matters. Documentary form shapes ways of thinking and seeing, just as it emerges from and shapes ideological assumptions.” Echoing the philosophies of Bertolt Brecht, they argue that “Politics and form are inextricably intertwined. One does not exist without the other.”

Reading their manifesto, one gets drawn into the sense of frustration they must have encountered during countless pitch sessions with producers, network executives, and streaming service curators. They are responding to what they have been told audiences really want, and what, by extension, the market wants and demands.

“Story” has become “today’s ubiquitous mantra, structure, telos, and mind-set,” they warn, cautioning that it “is only one of the many powerful forms of documentary.” While powerful documentaries have been “shaped into fabulous stories...storytelling is not the most or only effective form for documentary, as affecting as it can be. Not everything should be molded into a story [bold emphasis theirs], not everyone fits its constricting contours nor finds their most meaningful incantation in its familiar folds.”

These debates around form and content are hardly new, but the rapidly increasing financial clout that documentaries carry—something Michael Moore proved beyond any reasonable doubt after creating several “docbusters”—and the popularity of docu-series, has put new strain on any and all more radical diversions from what has emerged as the norm.

Juhasz and Lebow note that according to the Internet Movie Database (IMDb), thirteen of the twenty most financially successful documentaries have been made since 2000. Documentaries have now become big business and the profit motive is flattening the art form. “The millennial successes of documentary at the box office—and its many linked screens—has enabled a pressure, as well as baseline assumption, that “story” is the right or only approach to the form.” This they liken to Hollywood’s traditional need to hitch every social issue to star power (and effectively making the story about individual action rather than a collective movement), which often undermines the very social issue the film purports to champion. When reviewing Erin Brockovich (2000) at the time of its release, for example, I commented that it was clearly a film about Julia Roberts’s wardrobe and snappy one-liners rather than a call to action to defend the environment.

The debates over storytelling also reflect the tension between fiction versus nonfiction filmmaking. Hollywood has a long history of prefacing films with the “based on a true story” tagline, drawing audiences into the idea they are watching reality. The influence of Hollywood’s set number of narrative structures has drawn documentary filmmakers to adopt those structures—many of them clearly problematic. In his memoir, Staley relates his own account of intervening during the preproduction of the 2013 dramatic feature Dallas Buyers Club. Director Jean-Marc Vallée had in fact seen How to Survive a Plague, and (presumably to make his film feel more “real”), asked Staley if he would like a small supporting role in the film. While that film clung to its strategy of luring the audience into a true story (it was shot very much like a documentary and on a shoestring budget), Staley was horrified to read the script, which made the real-life character Ron Woodroof heterosexual (he was gay in real life) and catered to the bizarre conspiracy theory that HIV does not cause AIDS. Staley lobbied furiously to have numerous changes made to the script, fully aware that such misinformation translates as verified information to many mainstream audiences. This chapter in Staley’s memoir is chilling, pointing out how the exchange between documentaries and fictionalized movies can lead to such egregious distortions.

But while the Juhasz/Lebow manifesto denounces the pressure to conform to certain strains of documentary storytelling, the authors are painstakingly diplomatic, recognizing that different filmmakers will opt for different means of conveying their ideas. Rather than prescribe, they plead for new discussions to take place for new possibilities to form, rather than relying on tired, overworked strategies.

Breaking the Second Silence Around HIV/AIDS

A protest sign in United in Anger.

Regardless of their strategies, How to Survive a Plague and United in Anger, along with two documentaries that preceded them in 2011, We Were Here (David Weissman and Bill Weber’s intense account of how activists responded when AIDS first broke out in San Francisco) and Vito (Jeffrey Schwartz’s elegiac biopic of the legendary activist and author Vito Russo), were crucial in bringing an end to what has come to be known as the “second silence” around HIV/AIDS.

The first silence is identified as the utter and complete lack of the Reagan administration to respond to the epidemic when it was first identified. (AIDS had been identified as a “gay plague” as early as 1981, but it took then-President Reagan until 1985 to utter the word “AIDS” publicly.) But the second silence arrived after 1996, when drug cocktails improved the survival rates of those living with AIDS dramatically; many perceived it as a shift from AIDS as a fatal disease to HIV as a condition that was treatable. Sadly, this led many—including Andrew Sullivan and Dan Savage—to declare that the AIDS crisis was over.

Critics were quick to point out that this “end” to the crisis extended only to those people who could afford the costly drug regimen and to those who lived in parts of the world with advanced healthcare systems and sturdy social-safety nets. AIDS and its accompanying crises, of course, never really ended—and while it did evolve, and obituary sections of newspapers in queer urban enclaves in North America and Western Europe shrunk, those who were HIV-positive continued to face huge obstacles and significant discrimination and vilification, including from within the queer community.

These declarations were part of what led to what British writer and activist Dan Glass has referred to as the “second silence”—he argued that much of the LGBTQ movement shifted focus to battles like serving openly in the military to legalization of same-sex marriages. This silence may have had to do with apathy, but it was also connected to the trauma of the AIDS crisis, when it was at its very worst. People who lived through it wanted to forget or move on, even if it was just for a brief period.

The silence was also felt in culture. In a 2004 edition of the Canadian film magazine Take One, I identified what I saw as a reluctance or negligence of filmmakers to talk or write about HIV/AIDS, a topic that had once inspired several features. This shift, I noted, was perhaps best signified by Les invasions barbares (The Barbarian Invasions), Denys Arcand’s Oscar-winning 2003 sequel to his 1986 film Le Déclin de l’empire Américain (The Decline of the American Empire). In the first film, the gay character Claude (Yves Jacques) is suffering from an unnamed malady, which includes (according to his own complaints) excessive night sweats and weight loss (in a film about moral decay, the ailment was clearly coded as AIDS). But in the sequel, Claude is alive and well and apparently entirely free of whatever he had in the first film, now happily married to his male sweetheart. The sequel declined to even make fleeting reference to the obvious collapse of the character’s immune system in the first film, while attempting to point to a bruising irony: the only happy, stable couple in the sequel are queer, indicating just how “upside down” the entire planet has become. I referred to this phenomenon as “epidemic amnesia,” the name reflecting both a lack of memory about the epidemic and how widespread this ignoring of recent history had spread.

Thus, these four landmark documentaries must be credited with committing an imperative bit of social justice and activism: they shattered the second silence and jarred people from a collective amnesia, reminding us of the trauma, lives lost, and the ongoing multiple crises that HIV/AIDS constitute.

Despite their varying strategies, taken together they must be credited with reigniting discussion of a traumatic and appalling period in history, when many looked away in apathy as thousands of people died of a horrific disease, something that could be likened to a no-fault genocide achieved through apathy and government inaction. The second silence was shattered, paving the way for further activism, and for storytelling that tackled AIDS/HIV very directly, such as the American series Pose (2018–21) and the British miniseries It’s a Sin (2021). (Interestingly enough, the creators and writers of Pose acknowledged that much of their inspiration was the 1990 landmark queer documentary Paris Is Burning, a film that received some criticism for its lack of discussion of the AIDS epidemic.) For that feat, these films have earned their praise, and their rightful place in both film and activist history.

As Staley told me when I interviewed him in August about his memoir, “These films broke the second silence. I can speak as an authority on this, and 2012 was pivotal to reinvigorating AIDS activism. That the creators of these two projects [United in Anger and How to Survive a Plague] have basically been at war ever since is both depressing and petty, in the larger scheme of what was achieved.”

Distribution Sources:

How to Survive a Plague is distributed by IFC Films and is available for viewing on Amazon Prime.

United in Anger: A History of ACT UP is distributed by Kanopy.

Matthew Hays is co-editor (with Tom Waugh) of the Queer Film Classics book series and teaches film studies at Concordia University and Marianopolis College in Montreal.

Copyright © 2021 by Cineaste Magazine

Cineaste, Vol. XLVII, No. 1