“Films from the Czechoslovak New Wave”: Vojtĕch Jasný’s Desire (1958) and All My Good Countrymen (1969) and Jiří Menzel’s Larks on a String (1969) (Web Exclusive)

Reviewed by David Sterritt

Desire

Directed by Vojtĕch Jasný; written by Vojtĕch Jasný and Vladimir Valenta; cinematography by Jaroslav Kučera; edited by Jan Chaloupek; art direction by Karel Lier; music by Svatopluk Havelka; starring Jan Jakeš, Václav Babka, Jana Brejchová, Jiří Vala, Vĕra Tichánková, Václav Lohinský, Anna Melišková, and Jiří Pick. Blu-ray, 95 min., B&W, 1958.

All My Good Countrymen

Produced by Jaroslav Jílovec; directed and written by Vojtĕch Jasný; cinematography by Jaroslav Kučera; edited by Miroslav Hájek; art direction by Karel Lier; music by Svatopluk Havelka; starring Radoslav Brzobohatý, Vlastimil Brodský, Vladimir Menšik, Waldemar Matuška, Drahomira Hofmanová, Pavel Pavlovský, and Václav Babka. Blu-ray, 121 min., Color, 1969. A Second Run DVD release.

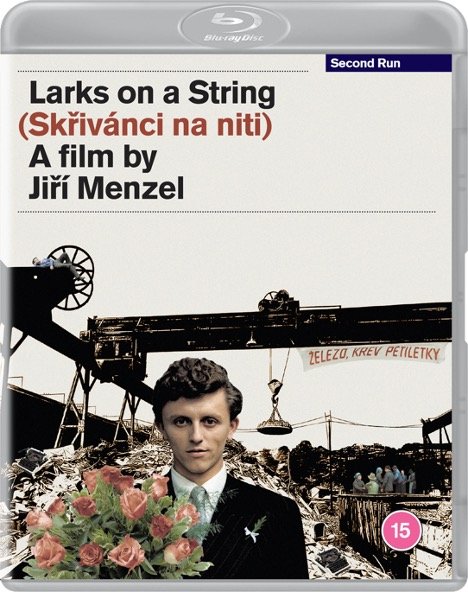

Larks on a String

Produced by Karel Kochman; directed by Jiří Menzel; written by Bohumil Hrabal and Jiří Menzel; cinematography by Jaromir Šofr; edited by Jiřina Lukešová; art direction by Oldřich Bosák; music by Jiří Šust; starring Rudolf Hrušinský, Václav Neckář, Jitka Zelenohorská, Vlastimil Brodský, Vladimir Ptáček, Leos Suchařípa, Ferdinand Krůta, Nada Urbanková, František Řehák, Jaroslav Satoranský, Zdenĕk Svĕrák, Vĕra Křesadlová, and Jiří Menzel. Blu-ray, 95 min., Color, 1969. A Second Run DVD release.

Of the many new movements that energized world cinema in the Fifties and Sixties, none was more intriguing than the Czechoslovak New Wave, which began in the early Sixties with films by Vĕra Chytilová and Miloš Forman, grew to maturity with works by Vojtĕch Jasný and Jaromil Jireš, and culminated with masterpieces by Jiří Menzel and Juraj Herz as the Sixties drew to a close. Like most such movements, it was sparked by young filmmakers reacting against the conventions of an older generation, and here the rules and strictures of Socialist Realism gave the newcomers—many of them alumni of Prague’s fabled Film and Television Academy of the Performing Arts (FAMU)—a large and exasperating target to attack. Their innovations were enabled by the general loosening of government control in the run-up to 1968, when Alexander Dubček came to power and the Prague Spring ushered in a period of “socialism with a human face.” When that period was crushed by a Soviet-led invasion after a few short months, a goodly number of New Wave films were promptly consigned to “the vault,” where pictures deemed too morally or politically liberal were left to languish. Since the end of the Cold War many have been rediscovered, restored, and widely distributed, and some fine specimens appear on two of Second Run DVD’s recent Blu-ray releases. Two Films by Vojtĕch Jasný is a two-disc set presenting Jasný’s portmanteau feature Desire, a pre-New Wave picture from 1958, and his 1969 pastoral epic All My Good Countrymen, as well as a third item, the 1950 docudrama It’s Not Always Cloudy, which he codirected with Karel Kachyňa as his FAMU graduation film. A separate Blu-ray presents Menzel’s sardonic Larks on a String, a 1969 comedy-drama audacious enough to set most of its action in a factory scrapyard. Taken together, the discs serve up a varied and mostly excellent program.

Jan Jakes in the first episode of Desire, trying to figure out the birds and the bees.

Jana Brejchová and Jirí Vala in the second chapter, “The People of the Earth and Stars in the Sky.”

Jasný started his career right after finishing his FAMU education, and anyone viewing It’s Not Always Cloudy, a celebration of collective farming influenced by Robert Flaherty and Italian neorealism, can see that the New Wave was immediately in high gear. Jasný and Kachyňa collaborated several more times in the next few years—their strong visual sense came from their training as both directors and cinematographers, film scholar Peter Hames notes in a booklet essay—and Jasný went solo in 1956. Two years later he made Desire, a set of four Moravian stories linked to the seasons of the year and to the evolution of life from youth to old age. The first chapter, “The Boy Who Wanted to Find the Edge of the World,” begins with a group of kids racing through a countryside as open and free as their own unbounded energy, and continues with one of them trying to get the lowdown on whether babies are really delivered by crows and storks. The second chapter, “The People of the Earth and Stars in the Sky,” centers on a young surveyor whose two passions are astronomy and hanging out with his beautiful girlfriend. The quiet sentiments of that story give way to earthier concerns in “Andĕla,” about a woman determined to resist the collectivization now required of the area’s farms, including hers. The collective leaps to her aid when sudden illness prevents her from carrying on her backbreaking work, but she soon returns to her plow, still refusing to participate in the new system, which has already degraded the quality of her holdings, as the film makes clear in a display of criticism that foreshadows the skepticism toward communism that would become a New Wave trademark. She is also seen praying and attending church, activities that became important to Jasný after the deaths of some loved ones turned him in spiritual directions. The final chapter, “Mother,” focuses directly on death, portraying a widowed schoolteacher in a rural village and two city-dwelling sons who visit her in the days before and after her passing. Like much of the film, this brief tale is gentle, humane, and lyrical in ways that Socialist Realism was doing its best to extinguish. Jasný regarded Desire as the foundation for all his subsequent work; it earned a “best selection” prize at the Cannes festival and initiated a longtime partnership with cinematographer Jaroslav Kučera.

Desire.

In a video interview in the Second Run set, Jasný says he couldn’t have made All My Good Countrymen before Joseph Stalin was dead and Dubček could personally greenlight the production. Those things happened, the film was made, and as soon as Dubček was gone it was ruthlessly suppressed. More than 100 features went “in the vault” when the Prague Spring ended, and a handful of these were “banned forever,” a status accorded to Forman’s The Fireman’s Ball (1967) and Jan Nĕmec’s A Report on the Party and Guests (1966) as well as All My Good Countrymen, which Jasný considered his most important creation.

Although it diverges from Desire by unfolding a single story, this film is again set in Moravia, and its shifting cast of characters and frequent leaps in time show a similar urge to experiment with temporality and depict multiple personality types. It spans the years from 1945, when World War II concluded and Communist reign was imminent, to 1958, by which time Communist bungling had brought about destructive waves of “careerism and vindictiveness within a community that previously enjoyed its own kind of balance,” in Hames’s words. There is also an epilogue set in 1968, expressing tentative hope for the future. The narrative has several important characters: Franta the tailer, Bertin the mail carrier, Josef the photographer, Joza the mason, Očenáš the intellectual church organist, Lispy the likable thief, Zášinek the well-off farmer, Janek the small farmer, and František, another farmer who eventually becomes the predominant figure. In the first episode, some children find a gun left over from wartime and take potshots at nearby grownups, darkly echoing the first part of Desire and establishing a blend of innocence and instability that escalates when farmers find and carefully detonate a land mine in a field. Jumping to 1948, tensions grow between villagers who embrace the Communist system and those who do not, and bureaucrats use their new power to seize private property and enforce questionable kinds of collectivism. In subsequent episodes the postal worker is murdered just before his wedding, a priest and others are falsely charged with the crime, the organist and his wife leave town, Zášinek has guilty visions of his Jewish wife, who died in a Nazi death camp, František goes to prison for defying Communist orders, then escapes and accepts a minor leadership post, and so on. In a terrific scene near the end, revelers wearing animal masks confront František and Josef on a snowy roadway—the mood is antic until Josef drops with a heart attack—and then gather at a tavern, ruefully predicting that the way things are going, animals will soon inherit the woefully mismanaged earth; as the audio commentary by Mike White, Spencer Parsons, and Chris Stachiw points out, this is like a flip-side version of George Orwell’s classic Animal Farm, with people becoming beastlike instead of vice versa. The film sensitively balances the personal and the political while keeping a deep connection with “the permanence of nature and of the seasons that dwarf human ambitions and conflicts,” to quote Hames again. It is also filled with superb portraiture, using closeups of weather-worn faces (mostly local residents, not actors) as expressive interludes. The narrative isn’t always crystal clear or gracefully conveyed, but its honesty and authenticity are unimpeachable. It thoroughly deserved its Best Director prize at Cannes (shared with Glauber Rocha’s 1969 landmark Antonio das Mortes), one of several wins and nominations Jasný received from that festival.

František (Radoslav Brzobohatý) in All My Good Countrymen.

Jasný made one more Czechoslovak film—the short 1969 documentary Bohemian Rhapsody, included in the Second Run set—and did a great deal of television work over the next three decades, but none of it in his native country, which he reluctantly fled when All My Good Countrymen was banned and the authorities aborted his next project. To keep working in Czechoslovakia, he said in a statement quoted in Hames’s essay, he would have needed to recant everything that made All My Good Countrymen his magnum opus. “That film was more than a decade in the making,” he declared, “and it is essentially a message that reaches from my parents and childhood neighbors all the way to where we were headed with the Prague Spring. And that is something I couldn’t possibly recant.” He kept on working in Austria, West Germany, and ultimately New York, and it’s wonderful that his final Czech feature is now more widely available than ever.

The reeducation candidates play music in Larks on a String.

Menzel never topped the international acclaim of his Academy Award-winning debut feature, the 1966 tragicomedy Closely Watched Trains, but Larks on a String may be closest to it in quality of acting and subtlety of mood. It’s one of five Menzel films based on works by the major Czech author Bohumil Hrabal, in this case a story collection that the writer and director shaped into an episodic narrative centered on an industrial plant where a motley crew of middle-class citizens have been sent for reeducation in the joys of working-class labor under watchful Communist eyes. The characters all have traits or backgrounds guaranteed to raise authoritarian eyebrows—a philosopher fond of Immanuel Kant, a librarian who circulated improper books, an attorney who defended the accused, a player of the decadent instrument called the saxophone, a religious man who observes the sabbath, and more of their suspicious ilk. The uselessness of the reeducation program amusingly shows in the first shots of the lazy, grumpy inmates, who mosey through their tasks under banners bearing hopelessly unpersuasive slogans (Why Not be Glad When Working For Ourselves?” “We’re Not Scared of Work/There’s No Target We’ll Shirk”) while scheming to make contact with the women in the adjacent quarters, who have the sense to divert themselves by actually keeping busy. Also in the mix are some Roma characters, whose presence brings out cultural confusions between minority and majority segments of Czech society, as White and Jonathan Owen note in their audio commentary.

Václav Neckár and Vera Kresadlová in Larks on a String.

Speaking in a Second Run video short called Jiří Menzel: 7 Questions, the aging director links his life with his country’s history, observing that the Nazis invaded in the year he was born, the Communists took over when he was 10, and the worst excesses of Stalinism held sway during his adolescence. He adds that nothing scared the authoritarians more than the middle classes and intellectuals, and this explains the callous treatment some unthreatening people received, often far harsher than anything in the mordantly amusing Larks on a String. It was duly banned after the Prague Spring, but Menzel avoided going into exile and was allowed to resume directing after a few years of involuntary hiatus. Hames reports that the film circulated on videocassettes in the Eighties, along with Jasný’s All My Good Countrymen and Jireš’s The Joke, and it scored a belated box-office success when it resurfaced in proper form in 1990. In my 1987 interview with Menzel for The Christian Science Monitor, he told me he didn’t have too many worries about criticizing his country in his films. “One can express much,” he said, “if one does it with gentleness and without hate.” The situation was obviously more complicated, but his humanist outlook shines through the deadpan wit of Larks on a String.

Copyright © 2022 by Cineaste Magazine

Cineaste, Vol. XLVIII, No. 1